Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison is the author of eleven novels, from The Bluest Eye (1970) to God Help the Child (2015). She received the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and in 1993 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. She died in 2019.

A LSO BY T ONI M ORRISON

Fiction

The Bluest Eye

Sula

Song of Solomon

Tar Baby

Beloved

Jazz

Paradise

Love

A Mercy

Home

God Help the Child

Nonfiction

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

The Origin of Others

The Source of Self-Regard

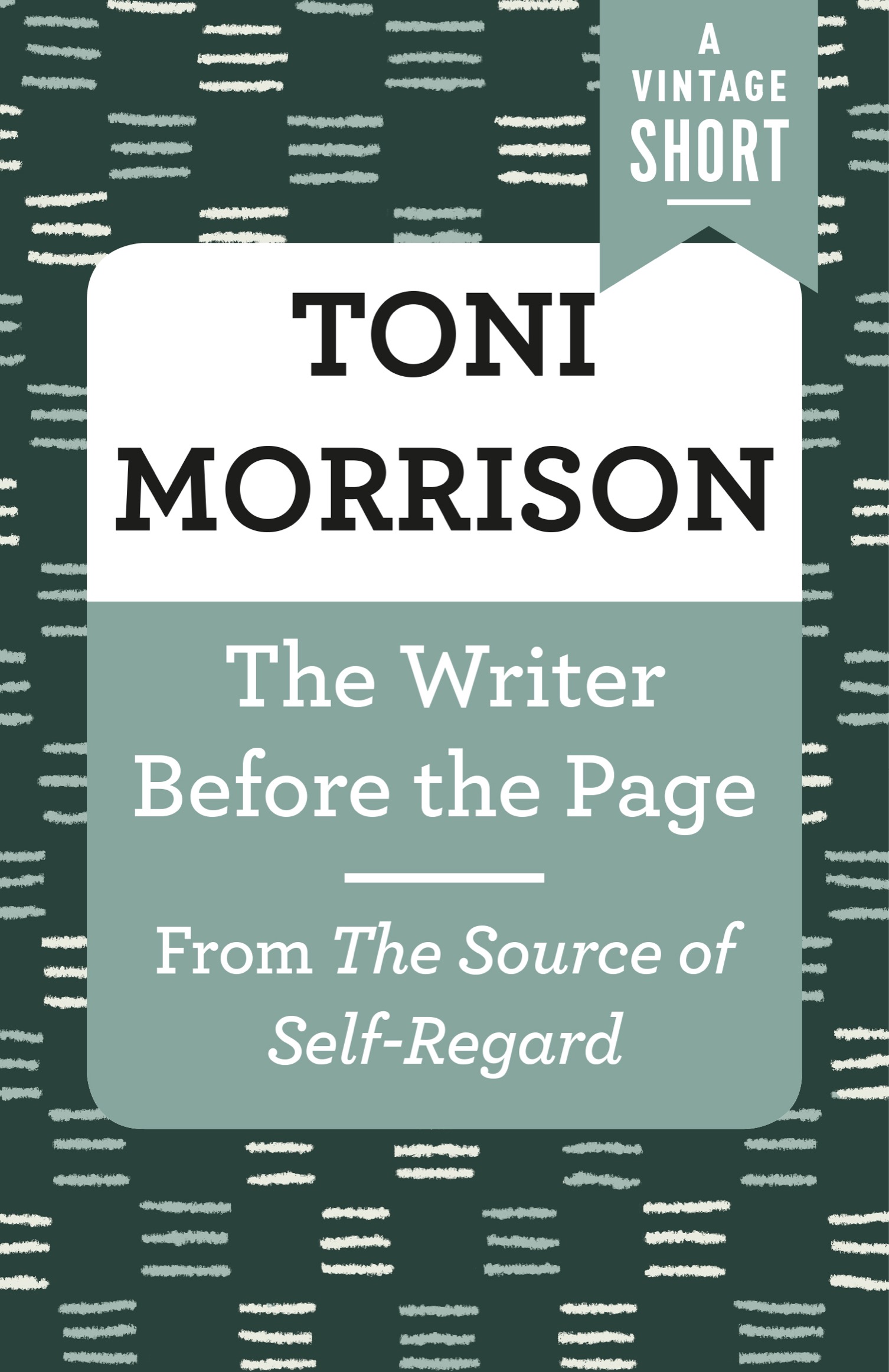

The Writer Before the Page

from The Source of Self-Regard

by Toni Morrison

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

Copyright 2019 by Toni Morrison

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 2019.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for The Writer Before the Page is available from the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN9780593082171

Cover design and illustration by Madeline Partner

www.vintagebooks.com

v5.4

a

Contents

The Writer Before the Page

I ONCE KNEW a woman named Hannah Peace. I say knew, but nothing could be less accurate. I was perhaps four years old when she was in the town where I lived. I dont know where (or even if) she is now or to whom she was related then. She was not even a visiting friend. And I couldnt to this day describe her in a way that would make her known in a photograph, nor would I recognize her if she walked into this room. But I have a memory of her and its like this: the color of her skinthe matte quality of it. Something purple around her. Also eyes not completely open. There emanated from her an aloofness that seemed to me kindly disposed. But most of all I remember her nameor the way people pronounced it. Never Hannah or Miss Peace. Always Hannah Peaceand more. Something hiddensome awe perhaps, but certainly some forgiveness. When they pronounced her name, they (the women and the men) forgave her something.

Thats not much, I know: half-closed eyes, an absence of hostility, skin powdered in lilac dust. But it was more than enough to evoke a characterin fact any more detail would have prevented (for me) the emergence of a fictional character at all. What is usefuldefinitiveis the galaxy of emotion that accompanied the woman as I pursued my memory of her, not the woman herself.

In the example I have given of Hannah Peace it was the having-been-easily-forgiven that caught my attention, and that quality, that easily forgivenness that I believe I remembered in connection with a shadow of a woman my mother knew, is the theme of Sula. The women forgive each otheror learn to. Once that piece of the constellation became apparent, it dominated the other pieces. The next step was to discover what there is to be forgiven among women. Such things must now be raised and invented because I am going to tell about feminine forgiveness in story form. The things to be forgiven are grave errors and violent misdemeanors, but the point was less the thing to be forgiven than the nature and quality of forgiveness among womenwhich is to say friendship among women. What one puts up with in a friendship is determined by the emotional value of the relationship. But Sula is not (simply) about friendship between women but between black women, a qualifying term the artistic responsibilities of which are what goes on before I ever approach the page. Before the act of writing, before the clean yellow legal pad or the white bond are the principles that inform the idea of writing. I will touch upon them in a moment.

What I want my fiction to do is to urge the reader into active participation in the nonnarrative, nonliterary experience of the text. And to refuse him makes it difficult for him (the reader) to confine himself to a cool and distant acceptance of data. When one looks at a very good painting, the experience of looking is deeper than the data accumulated in viewing it. The same, I think, is true in listening to good music. Just as the literary value of a painting or a musical composition is limited, so too is the literary value of literature limited. I sometimes think how glorious it must have been to have written drama in sixteenth-century England, or poetry in Greece before Christ, or religious narrative in 1000 AD , when literature was need and did not have a critical history to constrain or diminish the writers imagination. How magnificent not to have to depend on the readers literary associationshis literary experiencewhich can be as much an impoverishment of the readers imagination as it is of a writers. It is important that what I write not be merely literary. I am most self-conscious about in my work being overcareful in making sure that I dont strike literary postures. I avoid, too studiously perhaps, name-dropping, lists, literary references, unless oblique and based on written folklore. The choice of a tale or of folklore in my work is tailored to the characters thoughts or actions in a way that flags him or her and provides irony, sometimes humor.

Milkman, about to meet the oldest black woman in the world, the mother of mothers who has spent her life caring for helpless others, enters her house thinking of a European tale, Hansel and Gretel, a story about parents who abandoned their own children to a forest and a witch who made a diet of them. His confusion at that point, his racial and cultural ignorance and confusion, is flagged. Equally marked is Hagars bed being described as Goldilockss choice. Partly because of Hagars preoccupation with hair, and partly because, like Goldilocks, a housebreaker if ever there was one, she is greedy for things, unmindful of property rights or other peoples space, and Hagar is emotionally selfish as well as confused.

This deliberate avoidance of literary references has become a firm if boring habit with me, not only because it leads to poses, not only because I refuse the credentials it bestows, but also because it is inappropriate to the kind of literature I wish to write, the aims of that literature, and the discipline of the specific culture that interests me. (Emphasis on me.) Literary references in the hands of writers I love can be extremely revealing, but they can also supply a comfort I dont want the reader to have because I want him to respond on the same plane an illiterate or preliterature reader would have to. I want to subvert his traditional comfort so that he may experience an unorthodox one: that of being in the company of his own solitary imagination.

My beginnings as a novelist were very much focused on creating this discomfort and unease in order to insist that the reader rely on another body of knowledge. However weak those beginnings were in 1965, they nevertheless pointed me toward the process that engages me in 1982: trusting memory and culling from it theme and structure. In The Bluest Eye the recollection of what I felt and saw upon hearing a child my own age say she prayed for blue eyes provided the first piece. I then tried to distinguish between a piece and a part (in the way that a piece of a human body is different from a part of a human body).