O kay, gather round, everybody. Just a few things before we open the doors.

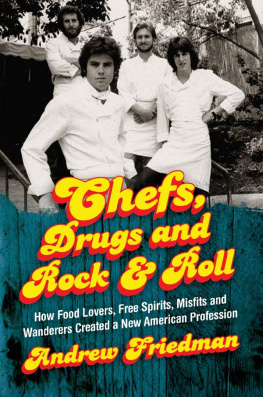

This first note is for the kitchen: What follows is intended as a narrative, impressionistic summary of the transformation of professional cooking in the United States during the 1970s, 80s, and early 90s. While many prominent chefs from the era are profiled, this book by no means constitutes a comprehensive survey of everybody who contributed to the industry over the twenty-plus years it covers.

In our interview, Patrick OConnell, chef-proprietor since 1978 of the landmark hotel and restaurant The Inn at Little Washington in Washington, Virginia, made a helpful point: We all have so many parallels. We had a party at Per Se for [the great French chef] Paul Bocuse; it was about thirty American chefs that Thomas Keller had invited and everybody was asked to stand for a moment and tell their story, and it usually involved some inspirational intersection with Bocuse and the great Michelin-starred restaurants of that era when we had nothing comparable yet in America. You would listen to their stories, and except for your own idiosyncrasy and personality, it was Oh my God. You had no idea we were all on the same trip and didnt even know each other.

With those parallels in mind, I have focused primarily on the broad historical strokes and on the central hubs where the most chefs were concentratedthe Bay Area, Los Angeles, and New York Cityand on game changers rather than those generally acknowledged to have been cooking the best or most influential food, although they are often the same. The example of La Cte Basque says a lot: Readers who were around in the 1970s and 80s will be surprised, if not scandalized, that Jean-Jacques Rachou casts a longer shadow here than Andr Soltner, but New York City cooks who were there will understand, and that decision should make sense to one and all by the time the dust clears.

With all of this in mind, many godlike talents, including some who took precious time to treat me to deeply revealing interviews, are scarcely mentioned, if at all, and related developments, such as the contemporaneous expansion of the American wine industry, have been necessarily relegated to the sidelines and footnotes.

Logic aside, please know that making these decisions caused me great personal anguish and was responsible for at least one lapsed deadline. And please accept my sincere apology if I failed to find the right spot to pay respect to you or your mentor.

For the dining room: In the interest of full disclosure, you should know that I have collaborated on books with many of the chefs in this storythough I have avoided it while working on this projectand count many more as friends and acquaintances. And so while I was fortunate to gain access to the breadth of people interviewed, Im also inclined toward discretion. All of which is to say that this book, despite its title, isnt by any means a tell-all, and that certain people known industry-wide for a range of illicit behaviors and weaknesses dont show any powder on their noses here, either because they wouldnt cop to it themselves or denied it on the record.

My wish was to write a strictly oral history, with the story told exclusively in the voices of the participants. But too many memories proved incomplete or flawed. So I consulted a mountain of books and periodicals and did more writing than originally planned, although the story is still largely carried by the words captured in a few hundred interviews. Quotations from those interviews (listed at the back of the book) are cast in the present tense (he says), whether the subject is living or deceased, while those from third-party sources are in the past tense (she said). Additional sources are listed by chapter at the back of the book as well. With everybodys best interest at heart, and with the consent of the participants, I have performed some minor editing on some quotations from my interviews to eliminate false starts, confusing colloquialisms, and the like; for elegance, I have avoided the use of ellipses to indicate omitted portions of quotations except where considerable text has been deleted. In no cases have my adjustments altered the speakers meaning.

Okay, thank you. Lets have a good service...

Andrew Friedman

We all had the same acid flashback at the same time.

Jonathan Waxman

Y ou could begin this story in any number of places, so why not in the back of a dinged-up VW van parked on a Moroccan camping beach, a commune of tents and makeshift domiciles? Its Christmas 1972. Inside the van is Bruce Marder, an American college dropout. Hes a Los Angelino, a hippy, and he looks the part: Vagabonding for six months has left him scrawny and dead broke. His jeans are stitched together, hanging on for dear life. Oh, and this being Christmas, somebody has gifted him some LSD, and hes tripping.

The van belongs to a coupleFrench woman, Dutch manwho have taken him in. It boasts a curious feature: a built-in kitchen. Its not much, just a set of burners and a drawer stocked with mustard and cornichons. But they make magic there. The couple has adventured as far as India, amassing recipes instead of Polaroids, sharing memories with new friends through food. To Marder, raised in the Eisenhower era on processed, industrialized grub, each dish is a revelation. When the lid comes off a tagine, he inhales the steam redolent of an exotic and unfamiliar herb: cilantro. The same with curry, also unknown to him before the van.

Like a lot of his contemporaries, Marder fled the United States. People wanted to get away, he says. Away from the Vietnam War. Away from home and the divorce epidemic. The greater world beckoned, the kaleidoscopic, tambourine-backed utopia promised by invading British rockers and spiritual sideshows like the Maharishi. The price of admission was cheap: For a few hundred bucks on a no-frills carrier such as Icelandic Airlinesnicknamed the Hippie Airline and Hippie Expressyou could be strolling Piccadilly Circus or the Champs-lyses, your life stuffed into a backpack, your Eurail Pass a ticket to ride.

Marder flew to London alone, with $800 and a leather jacket to his name, and improvised, crashing in parks and on any friendly sofa andif he couldnt score any of thatsplurging on a hostel. He let himself go, smoking ungodly amounts of pot, growing his hair out to shoulder length. In crowds, he sensed kindred spirits, young creatures of the road, mostly from Spain and Finland. Few Americans.

Food, unexpectedly, dominated life overseas. Delicious, simple food that awakened his senses and imagination. Amsterdam brought him his first french fries with mayonnaise: an epiphany. The souks (markets) of Marrakech, with their food stalls and communal seating, haunt him. Within five months, he landed on that camping beach, in Agadir, still a wasteland after an earthquake twelve years prior. He lived on his wits: Back home, hed become fluent in hippy cuisine; now he spent his last pennies on brown rice and vegetables, cooking them for strangers who shuttled him around. Just in time, people started feeding him, like the couple in whose van he was nesting. Food was as much a part of life on the beach as volleyball and marijuana. People cooked for each other, spinning the yarns behind the mealswhere theyd picked them up and what they meant in their native habitats. Some campers developed specializations, like the tent that baked cakes over an open burner. Often meals were improvised: Youd go to town, buy a pail, fill it with a chicken, maybe some yogurt, or some vegetables and spices, and figure out what to do with it when you got back.