Saadi Shirazi

(1210-c. 1291)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Browse the entire series

Saadi Shirazi

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

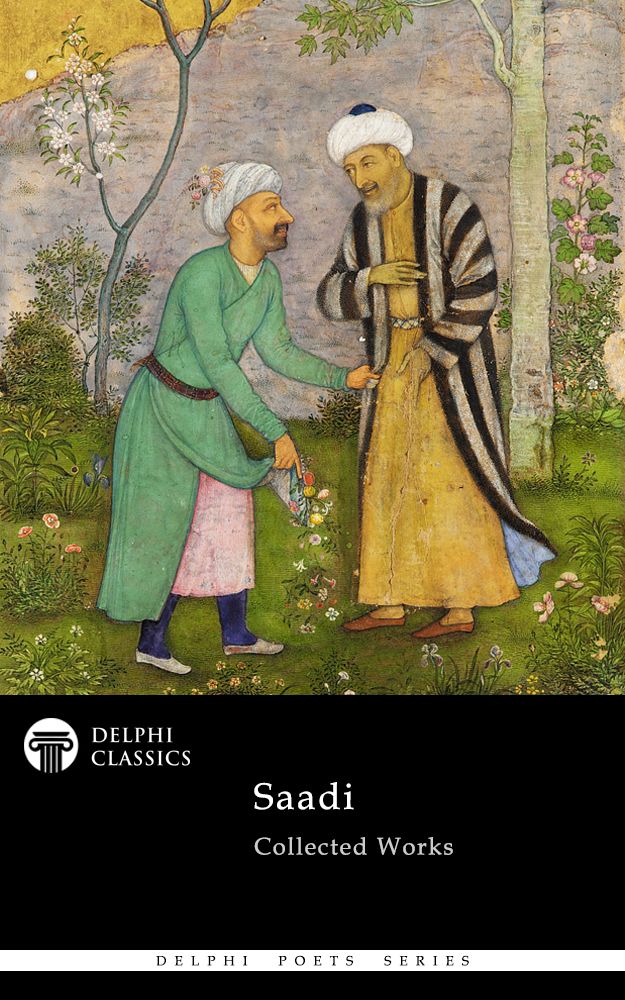

Saadi - Delphi Poets Series

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78877 971 5

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

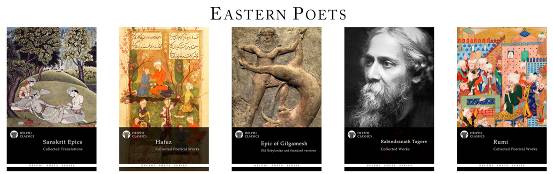

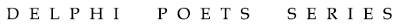

Interested in classic Eastern literature?

Delphi Classics is proud to present comprehensive editions of these important Eastern themed authors.

Explore Eastern Classics

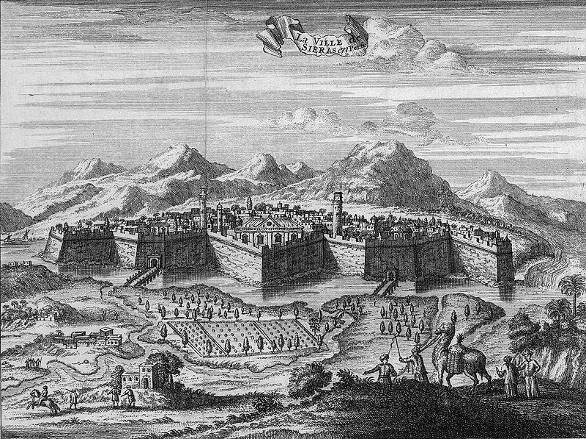

The Life and Poetry of Saadi Shirazi

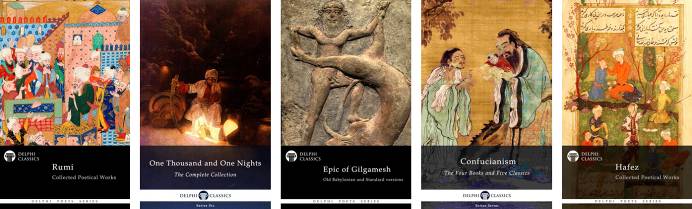

Shiraz, the fifth most populous city of Iran and the capital of the Fars Province. Saadis birthplace is one of the oldest cities of ancient Persia.

Imamzadeh Ali ebn e Hamze, Shiraz

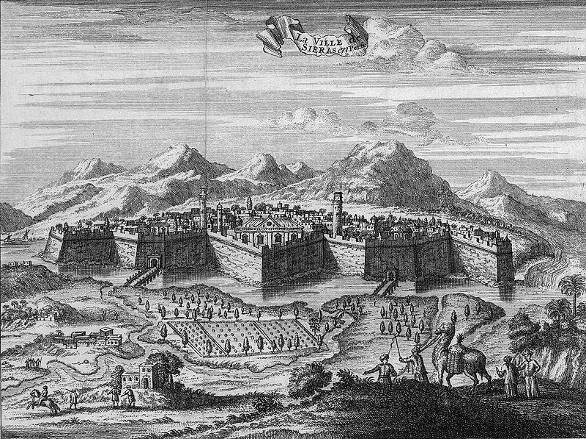

Jean Struys drawing of Shiraz in c. 1681

Brief Introduction: Saadi by Epiphanius Wilson

T HE PERSIAN POET Sadi, generally known in literary history as Muslih-al-Din, belongs to the great group of writers known as the Shirazis, or singers of Shiraz. His Gulistan, or Rose Garden, is the mature work of his life-time, and he lived to the age of one hundred and eight. The Rose Garden was an actual thing, and was part of the little hermitage, to which he retired, after the vicissitudes and travels of his earlier life, to spend his days in religious contemplation, and the embodiment of his experience in reminiscences, which took the form of anecdotes, sage and pious reflections, bon-mots , and exquisite lyrics. When a friend visited him in his cell and had filled a basket with nosegays from the garden of the poet with roses, hyacinths, spikenards, and sweet-basils, Sadi told him of the book he was writing, and added: What can a nosegay of flowers avail thee? Pluck but one leaf from my Rose Garden; the rose from yonder bush lasts but a few days, but this Rose must bloom to all eternity.

Sadi has been proved quite correct in this estimate of his own work. The book is indeed a sweet garden of unfading freshness. If we compare Sadi with Hafiz, we find that both of them based their theory of life upon the same Sufic pantheism. Both of them were profoundly religious men. Like the strong and life-giving soil out of whose bosom sprang the rose-tree, wherein the nightingales sang, was the fixed religious confidence, which formed the support of each poets mind, amid all the vagaries of fancy, and the luxuriant growth of fruit and flower which their genius gave to the world. Hafiz is the Persian Anacreon. As he raises his voice of thrilling and unvarying sweetness, his steps reel, he waves the thyrsus, and his flushed cheek shows the inspiration of the vine. To him the Supreme Being has much in common with the Indian or Thracian Dionysus, the god of perennial youth, joyous revel, and exhilaration. Hafiz can never be the guide, though he may be the cheerer of mortals, adding more to the gayety than to the wisdom of life. But both in the western and in the eastern world Sadi must always be looked upon as the guide and enlightener of those who taste life, and love poetry. It has been said by a wise man that poetry is the great instructor of mature minds. Many a man turning away in weariness from the controversies, the insincerities, and the pretentiousness of the intellectualists around him, has exclaimed, Give me my Horace. But Horace with all his bonhommie , his common sense, and his acuteness, is but the representative of a narrow Roman coterie of the Augustan age. How thin, flimsy, and unspiritual does he appear in comparison with the marvellous depth, the spiritual insight, the tenderness and power of expression which characterized Sadi.

Sadi had begun his life as a student of the Koran and became early imbued with the quietism of Islam. The cheerfulness and exuberant joy which characterize the poems he wrote before he reached his fortieth year, had bubbled up under the repressions of severe discipline and austerity. But the religion of Mohammed was soon exchanged by him, under the guidance of a famous teacher, for the wider and more transcendental system of Sufism. Within the area of this magnificent scheme, the boldest ever formulated under the name of religion, he found the liberty which his soul desired. Early discipline had made him a morally sound man, and it is the goodness of Sadi that lends such a warm and endearing charm to his works. The last finish was given to his intellectual training by the travels which he took after the Tartar invasion desolated Persia, in the thirteenth century. India, Arabia, Syria, were in turn visited. He found Damascus a congenial halting-place, and lived there for some time, with an increasing reputation as a sage and poet. He preached at Baalbec on the fugitiveness of human life, on faith, love, and rest in God. He wandered, like Jerome, in the wilderness about Jerusalem, and worked as a slave in Africa in the trenches of Tripoli: he travelled the length and breadth of Asia Minor. When he arrived back at Shiraz, he had passed the limit of three-score years and ten, and there he remained in his hermitage and his garden, to arrange the result of all his studies, his experiences, and his sufferings, in that consummate work which he has named the Rose Garden, after the little cultivated plot in which he spent his declining days and drew his last breath.

Next page