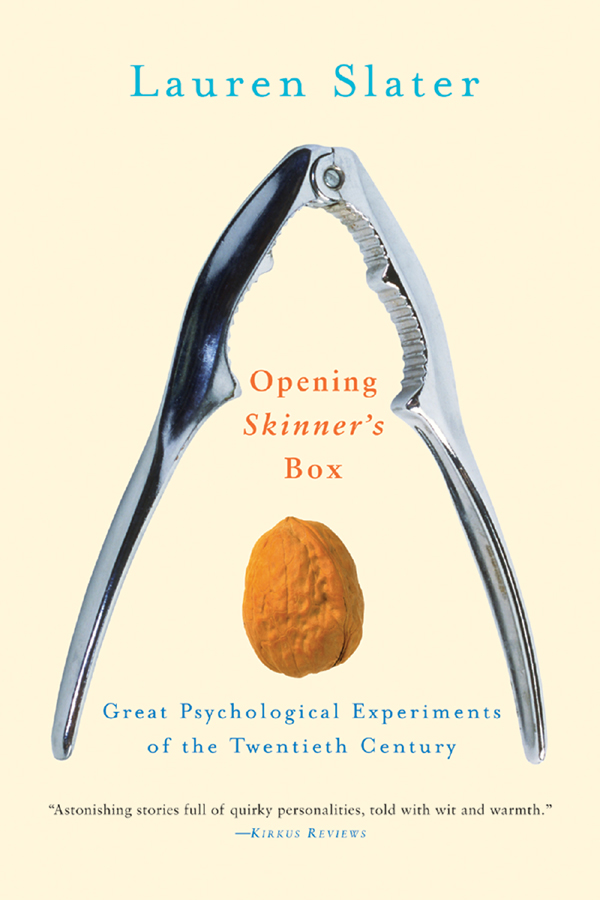

Opening

Skinners

Box

GREAT PSYCHOLOGICAL

EXPERIMENTS OF THE

TWENTIETH CENTURY

Lauren Slater

IN MEMORY OF PSYCHOLOGIST AND PROFESSOR SIGMUND KOCH

MENTOR, FRIEND

Contents

I did my first psychological experiment when I was fourteen years old. There were raccoons living in the walls of our old Maine vacation house, and one day I stuck my hand in the crumbling plaster and pulled out a squalling baby, still milk-smeared, its eyes closed and its tiny paws pedaling in the air. Days later the sealed eye slits opened, and because Id heard of Konrad Lorenz and his imprinted ducklings, I made sure the mammal saw me first, its streaming field of vision taking in my formhands and feet and face. It worked. Immediately the raccoonI called her Amelia Earheartbegan to follow me everywhere, wreathing around my ankles, scrambling up my calves when she was afraid. She followed me to the town bookstore, to school, down busy streets, into bed, but in truth, I began to take on more of her behaviors than she mine. Even though I was the imprinter, with Amelia at my side I learned to fish in a pond with my human paws; I learned to latch on to the soft scree at the base of a rotting tree and climb; I learned the pleasures of nocturnity, the silver-wet grass, black rings beneath my tired eyes. The results: Imprinting, I wrote in my science notebook, happens to the mother too. Who, I wondered, influenced whom in this symbiotic pairing? Could species shift from their specific shapes and become, through exposure, something altogether other? Was there really a boy raised by wolves, a chimpanzee who signed with words? The questions fascinated me then, and still do today. More fascinating to me became, over time, as I grew older, the means by which one explored these questions: the hypothesis, the experimental design, the detailed qualitative description, the breathless or boring wait for results. I was first hooked on Amelia and later hooked on the pure plot that structures almost all psychological experiments, intentional or not.

While it would be reductive to say a raccoon rests at the bottom of this book, Amelia is certainly the image that comes to mind when I think of its etiology. Beyond that, I have for a long time felt that psychological experiments are fascinating, because at their best they are compressed experience, life distilled to its potentially elegant essence, the metaphorical test tube parsing the normally blended parts so you might see love, or fear, or conformity, or cowardice play its role in particular circumscribed contexts. Great psychological experiments amplify a domain of behavior or being usually buried in the pell-mell of our fast and frantic lives. Peering through this lens is to see something of ourselves.

When I studied psychology in graduate school, I again had the chance to perform experiments and observations on all sorts of animals. I saw the embryo of an angel fish grow from a few single cells to a fully finned thing in forty-eight hours flatlife putting together its puzzle pieces right before my eyes. I saw stroke victims deny the right sides of their faces and blindsight patients mysteriously read letters despite their dead eyes. I observed people waiting for elevators and had this as my salient question: Why is it that people continuously press the button when theyre waiting in the lobby, even though they know, if interviewed, that it wont make the elevator come any faster? What does elevator behavior say about human beings? I also, of course, read the classic psychological experiments where they had been housedin academic journals, mostly, replete with quantified data and black-bar graphsand it seemed somewhat sad to me. It seemed sad that these insightful and dramatic stories were reduced to the flatness that characterizes most scientific reports, and had therefore utterly failed to capture what only real narrative cantheme, desire, plot, historythis is what we are. The experiments described in this book, and many others, deserve to be not only reported on as research, but also celebrated as story, which is what I have here tried to do.

Our lives, after all, are not data points and means and modes; they are storiesabsorbed, reconfigured, rewritten. We most fully integrate that which is told as tale. My hope is that some of these experiments will be more fully taken in by readers now that they have been translated into narrative form.

Psychology and its allied professions represent a huge disparate field that funnels down to the single synapse while simultaneously radiating outward to describe whole groups of human beings. This book does not contain, by any means, all the experiments that represent the reach of that arc; it would take volumes to do that. I have chosen ten experiments based on the input of my colleagues and my own narrative tastes, experiments that for me and others seem to raise the boldest questions in some of the boldest ways. Who are we? What makes us human? Are we truly the authors of our own lives? What does it mean to be moral? What does it mean to be free? In telling the stories of these experiments, I revisit them from my contemporary point of view, asking what relevance they have for us now, in this new world. Does Skinners behaviorism have meaning for current-day neurophysiologists who can probe the neural correlates of his habit-driven rats? Does Rosenhans horrifying and comedic experiment on mental illness, its perception and diagnoses, still hold true today, when we supposedly abide by more objective diagnostic criteria in the naming of disease? Can we even define as disease syndromes that have no clear-cut physiological etiology or pathophysiology? Is psychology, which deals half in metaphor, half in statistics, really a science at all? Isnt science itself a form of metaphor? A long time ago, in the late 1800s, Wilhelm Wundt, long considered psychologys founding father, opened one of the first instrument-based psychology labs in the world, a lab dedicated to measurement, and so a science of psychology was born. But as these experiments demonstrate, it was born breech, born badly, a chimerical organism with ambiguous limbs. Now, over one hundred years later, the beast has grown up. What is it? This book doesnt answer this question, but it does address it in the context of Stanley Milgrams shock machine, Bruce Alexanders addicted rats, Darley and Latans smoke-filled rooms, Monizs lobotomy, and other experiments as well.

In this book we see how psychology is inevitably, ineluctably, moving toward a deeper and deeper mining of biological frontiers. We see how the clumsy cuts of Moniz transformed, or transmogrified, depending on your point of view, into the sterile bloodless surgery called cingulotomy. We hear about the inner workings of a neuron, and how genes encode proteins that build those blue eyes, that memory, right there. And yet, while we can explain something of the process and mechanisms that inform behavior and even thought, we are far from explaining why we have the thoughts, why we gravitate toward this or that, why we hold some memories and discard others, what those memories mean to us, and how they shape a life. Kandel, or Skinner, or Pavlov, or Watson can demonstrate a conditioned response, or operant, and the means by which it gets encoded in the brain, but what we do with that information once its there depends on circumstances outside the realm of science entirely. In other words, we may be able to define the physiological substrates of memory, but in the end we are still the ones who weave, or not, still the ones who work the raw material into its final form and meaning.

Next page