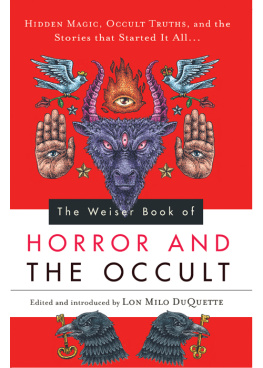

The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories

Perhaps no figure better embodies the transition from the Gothic tradition to modern horror than Arthur Machen. In the final decade of the nineteenth century, the Welsh writer produced a seminal body of tales of occult horror, spiritual and physical corruption, and malignant survivals from the primeval past which horrified and scandalized late Victorian readers. Machens weird fiction has influenced generations of storytellers from H. P. Lovecraft to Guillermo Del Toro, and it remains no less unsettling today.

This new collection, which includes the complete novel The Three Impostors as well as such celebrated tales as The Great God Pan and The White People, constitutes the most comprehensive critical edition of Machen yet to appear. In addition to the core late-Victorian horror classics, a selection of lesser-known prose poems and later tales helps to present a fuller picture of the development of Machens weird vision.

Arthur Machen was born in 1863 in Caerleon, Monmouthshire, the son of a Welsh clergyman. His birthplace, rich in history and legend, was to have a decisive impact on his later fiction. Machen attended Hereford Cathedral School, but his fathers poverty precluded a university education. During the 1880s Machen worked in London as a tutor, translator, and cataloguer, while finding his way as a writer. Then, between 1890 and 1900, he produced a body of tales of horror, wonder, and the borderland between the two. The most popular, or notorious, of these in its day was The Great God Pan, associated, then and now, with the Decadent movement in literature. Pan and other works written during that decade, including The Three Impostors, The Hill of Dreams, and The White People, are now recognized as classics of weird fiction. At the start of the First World War, Machen caused a stir with a short story about a supernatural rescue of an English company at Mons, The Bowmen, which many readers refused to accept as fiction. Despite Machens very high reputation among other weird writers, his popular appeal, even to fans of horror and the supernatural, has ever waxed and waned. Machen died at St Josephs Nursing Home in Beaconsfield in 1947.

Aaron Worth is an Associate Professor of Rhetoric at Boston University. He is the author of Imperial Media: Colonial Networks and Information Technologies in the British Literary Imagination, 18571918 (2014), as well as critical essays discussing the work of such Victorian horror writers as Arthur Machen, M. R. James, and Richard Marsh. His own horror fiction has appeared in publications including Cemetery Dance Magazine and Aliterate.

Cover image: PictuLandra/Shutterstock

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Selection and editorial material Aaron Worth 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of theabove should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017950098

ISBN 9780198813163

ebook ISBN 9780192549570

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Acknowledgements

In preparing this edition I have benefited from the generous assistance of several Machen scholars; I must particularly thank Mark Valentine and James Machin for their help on several points of information. I am grateful as well to the following for expert opinion, advice, and aid of various kinds: Millard Baublitz, Mark Bills, Michael Booth, Peter Brabham, Godfrey Brangham, William Charlton, Barry Faulk, Billy Flesch, James Gregory, James Hamill, Gregg Jaeger, Darryl Jones, Roanne Kantor, Valerie Lester, Roger Luckhurst, Natalie McKnight, Jim Mussell, Tom Noel, Bob Patten, Aidan Reynolds, and Justin Willis. Finally, I owe thanks to my editor, Luciana OFlaherty, for making this book possible; to Kizzy Taylor-Richelieu, Rowena Anketell, Lisa Eaton, and everyone else at Oxford University Press for their expertise and assistance; and to the projects anonymous readers for their perceptive comments and suggestions.

Contents

Readers who are unfamiliar with the stories may prefer to treat the Introduction as an Afterword.

In 1895 the editors of a new magazine, The Unicorn, sought to make a splash by engaging a pair of literary hot properties to contribute parallel series of tales. The two writers were Arthur Machen and H. G. Wells, both fresh from recent publishing triumphs (perhaps in Machens case scandal is closer to the mark), and their respective contributions were to offer readers distinct modes, or flavours, of what we should today call genre fiction. The magazine, unfortunately, folded after a mere three issues, in which only one of Wellss stories, and none of Machens, appeared. Machen related the episode, nearly three decades later, in characteristically self-deprecating fashion:

The Great God Pan had made a storm in a Tiny Tots teacup. And about the same time, a young gentleman named H. G. Wells had made a very real, and a most deserved sensation with a book called The Time Machine; a book indeed. And a new weekly paper was projected by Mr. Raven Hill [sic] and Mr. Girdlestone, a paper that was to be called The Unicorn. And both Mr. Wells and myself were asked to contribute; I was to do a series of horror stories.

This obscure episode in late Victorian publishing history is intriguing for a number of reasons. It would be interesting to know, for instance, just how Raven-Hill and Girdlestone phrased their offer; perhaps they requested more stuff in the Pan line. Writing in the 1920s, Machen speaks of horror stories and tales of horror, but it is unlikely that these were the expressions used at the time (unlikely, too, that the editors asked the young Wells for more scientific romances, let alone the entirely anachronistic designation science fiction). This was, after all, precisely the period during which the still-fluid conceptual boundaries of emergent genre categories like science fiction, fantasy, and horror were themselves beginning to be negotiated, shaped, and defined. But a more tantalizing question is this: if The Unicorn, and its editors scheme, had been a success, would the trajectory of Machens reputation have more closely resembled that of Wells, who went on to score triumph after triumph, as well as worldwide celebrity, in the years to come? Machens star, by contrast, sank slowly back towards the horizon line of relative obscurity, then followed an irregularly wave-like course throughout his later life (and afterlife), ascending and again declining at periodic intervals. For Wells, 1895 marked the beginning of fame; for Machen it meant something like the end of it, until the next century at any rate. But what if Machen had become, as it were, the H. G. Wells of horror?