Belloc - Charles II

Here you can read online Belloc - Charles II full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Chicago, year: 2008;2003, publisher: IHS Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Charles II: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Charles II" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

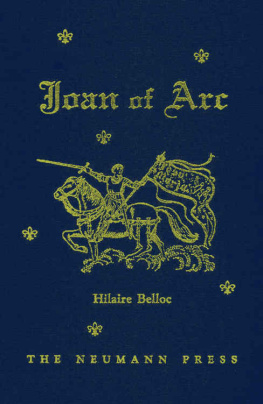

Belloc: author's other books

Who wrote Charles II? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Charles II — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Charles II" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Tom T., with sincere thanks.

Charles II: The Last Rally.

Copyright 2003 IHS Press.

Charles II copyright the Estate of Hilaire Belloc.

Preface, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright IHS Press.

All rights reserved.

Charles II was originally published in 1939 by Harper & Brothers Publishers of New York and London. Cassell and Co., Ltd., of London issued an edition the following year, which edition forms the basis of the present edition. The spelling, punctuation, and formatting of the Cassell edition have been largely preserved. Minor corrections to the text have been made in light of the earlier edition.

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-34-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Belloc, Hilaire, 1870-1953

Charles II: the last rally / by Hilaire Belloc.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Harper & Brothers, 1939.

ISBN 0-9718286-4-4 (alk. paper)

1. Charles II, King of England, 1630-1685. 2. Great

BritainHistoryCharles II, 1660-1685. 3. Great

BritainKings and rulersBiography. I. Title.

DA445.B38 2003

941.064092dc21

2003042384

Printed in the United States of America.

Gates of Vienna Books is an imprint of IHS Press.

For more information, write to:

Gates of Vienna Books

222 W. 21st St., Suite F-122

Norfolk, VA 23517

by Dr. John P. McCarthy

C HARLES II: T HE L AST R ALLY

Charles JJ in Coronation Robes

A N OIL PAINTING BY J. M. W RIGHT , 1661

This book, one of the last that Belloc wrote, appeared in 1939 when he was 69 three years before a stroke that ended his literary career. Its theme and message did not depart from that of his many popular biographies written in the 1920s and 30s. Those works were all based upon the same premises that characterized his general approach to and understanding of European history. Foremost among those premises is the notion proclaimed in his 1920 work, Europe and the Faith: The Faith is Europe. And Europe is the Faith. That meant that European civilization was the creature of Catholicism and to the degree that Europe departed from Catholicism, she would loose her identity. And if that happened, Europe would come to signify just a geographical area or as seems the case today a mere economic and administrative unit, lacking any spiritual or cultural basis.

Belloc saw as providential the link between classical Roman Civilization and Christianity. The Church was able to employ the structures and the thought of Rome for its own development while preserving Roman Civilization, making it, in baptized form, the civilization of Europe. This view contrasted strikingly with that of Gibbon and other Enlightenment-era thinkers who blamed Christianity for Romes decline.

And what of the barbarian invasions and the so-called Dark Ages that followed the political collapse of Rome? Belloc viewed the barbarians not as conquerors, but as immigrants, themselves aspiring to be part of Rome. Administrative and economic weaknesses in the empire enabled the newcomers increasingly to assume authoritative roles, but as Roman officials, not as conquerors. These quasi-Romans also accepted Christianity, which had become the religion of the empire. That religion, especially through its monastic orders, preserved the classical heritage during the disorderly centuries that ensued, when socio-economic structures had become rather primitive, and when the territory of the old empire faced invasions by non-Christian Vikings and Islam.

Belloc certainly did not accept the popular view of early medieval English history, which held that the inherent self-governing abilities of the Anglo-Saxon settlers had enabled them to prevail over the Celtic Britons and the few surviving Roman-Britons. Rather, he saw Anglo-Saxon success in dominating England as having come from their acceptance of the Christian message of St. Augustine. In his analysis of later-medieval English history, he emphasized the reforming and civilizing role of the Norman kings and their successor sovereigns in promoting law, parliament, and the general development of civilization. This view contrasted decidedly with the popular notion that the democratic Anglo-Saxons were conquered by the Normans, and that British constitutional history since then is simply the story of the Anglo-Saxon effort to restrain the encroachments of the Norman monarchy upon popular freedoms.

Naturally, Belloc regarded the Reformation of the sixteenth century as the disastrous disruption of European unity. He thought the Reformation need not have endured, as much of it consisted of localized, reformist zealotries prompted by serious grievances and abuses. It was made lasting, however, when England was lost to the Church. That loss was closely linked to the rise of a landed oligarchy, enriched at the expense of the Church, and which over a century or more fatally weakened the monarchy that had favored that enrichment. The last hope for blocking that oligarchic ascendancy existed during the reign of Charles II. Hence, the last rally.

Bellocs unconventional historical vision has to be understood in large part as a reaction against the historical views prevalent when he came of age in late nineteenth-century England the era in European history labeled by the late historian Carlton Hayes as the Generation of Materialism. Then popular was an intellectual progressivism that regarded the latest age as the most intelligent, and which expected human progress on the basis of scientific development to be inevitable. Central to this scientifically determinist materialism was Social Darwinism, which interpreted human relations according to the Darwinist explanation of the evolution of species. Prevailing historical attitudes worked hand-in-glove with this progressivist determinism, as seen, e.g., in the already mentioned Anglo-Saxon myth about the inherent self-governing ability of the forebears of the English-speaking world.

Also common to that era was what historian Herbert Butterfield labeled Whig History: the tendency of historians to write favorably of the winners in historical confrontations, especially if the winners were Protestants and/or liberals (but not necessarily revolutionaries, like the French Jacobins). Such seems the case in modern British history, which has an historical vision running as follows: the Reformation in England was the victory of religious liberty against Papal despotism; in succeeding centuries the monarchy that had brought on the Reformation was itself brought under control by the parliament; and parliament itself, over time, became more and more democratically controlled. Events of the later nineteenth century worked to confirm this Whig-Progressivist vision, as the Protestant and industrial societies seemed to prevail over Catholic and/or agrarian and traditional societies, e.g., the North in the American Civil War, Prussia in the struggles with Austria for the unification of and domination over the Germanies, Lombardy-Sardinia against the Papal States, the relationship between England and Ireland, and the defeat of Emperor Louis Napoleon in the Franco-Prussian War (which started two days after Belloc was born).

British Imperialism had reached its peak in Bellocs early manhood. By that time it had been transformed from a pattern of purely diplomatic and military involvements in distant lands for limited, specific objectives, to a popular ideology endorsing the extension of the British flag to the four corners of the globe. Another now-forgotten but then-fashionable intellectual trend in England was a strong Germanophilia, whether in neo-Hegelian philosophy, the racial identification of the Anglo-Saxons with the modern Germans, or simply an admiration for the technical, administrative, and economic ability of the Germans in terms of education, public service, and industrialization.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Charles II»

Look at similar books to Charles II. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Charles II and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.