Rubin Dominic - Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era

Here you can read online Rubin Dominic - Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: C. Hurst and Company (Publishers) Limited, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era

- Author:

- Publisher:C. Hurst and Company (Publishers) Limited

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

41 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3PL

Dominic Rubin, 2018

All rights reserved.

Printed in the USA

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

The right of Dominic Rubin to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78738-089-9

www.hurstpublishers.com

.

.

This book had its origins in two courses I taught at Dickinson College, Pennsylvania in 2013-2014: Religion and Communism and Islam in Eurasia. The invitation to come and teach for two years at Dickinson was due to Professor Elena Duzs, and it was also she who suggested I teach a course on Islam in the post-Soviet region, and so I would like to thank her for getting the ball rolling. I would also like to thank Dickinson College for giving me a grant to travel to Kyrghyzstan in 2013.

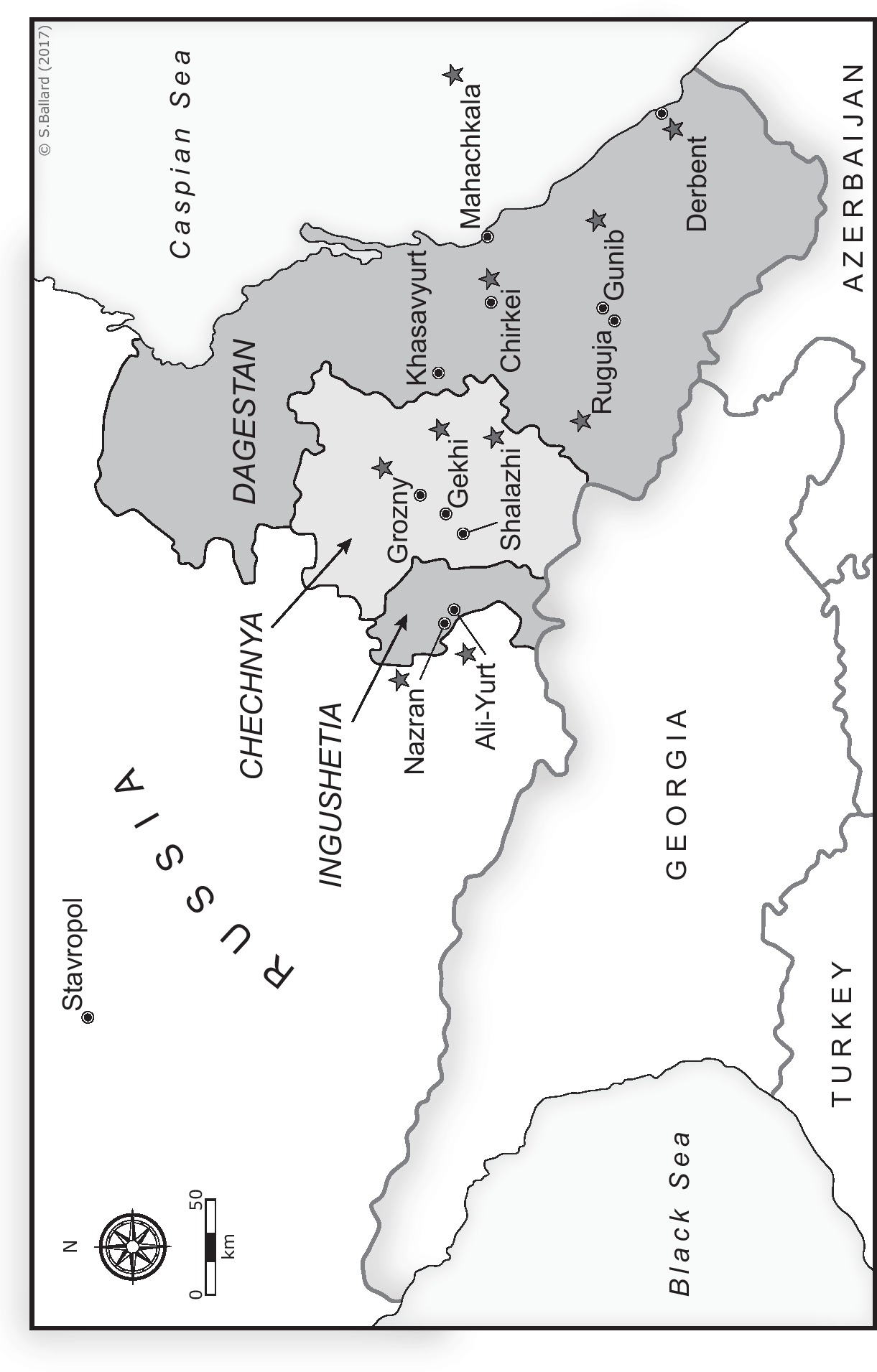

Back then, I had just finished a book on the Russian Eurasianist philosopher, Lev Karsavin, and I was trying to square the interest in the East proclaimed by Russian Eurasianists with their perplexing lack of knowledge and real understanding of Eastern religions and philosophies. As I commuted between Russia and the U.S., and started reading up for my new Islam course, I also decided to deepen my own knowledge of Islam and Muslims in Russia. Eventually, I began to see a certain gap in the literature. There seemed to be quite a number of books that were oriented towards the security angle, and quite a few histories of Tsarist- and Soviet-era Russian Islam; there were also books that gave sociological surveys of Muslims beliefs and others that listed the multitude of rapidly shifting contemporary Muslim organizations. However, it was difficult to hear the voices of individual Muslims, or make sense of how being Muslim and being Russian were being combined at the individual level since the collapse of the Soviet Union. I thus decided to plunge right in and begin speaking to as many Muslims as I could meet, with the idea of writing down their views and life stories, and hoping that I would get some sense of where the Muslim community in Russia was going. After four years, this is the result, and I hope that the book does put a personal, human face on the Russian Muslim community today. It will not replace the existing books, of course, but hopefully act as a useful supplement.

In the early days, I was beholden to Anna Gorbenko, my sister-in-law, for introducing me to her Tatar acquaintances; to Professor Marion Wyse, for putting me in touch with some of her Tatar and Dagestani students; to Ian Pryde and Ainura Maketova, for hosting me in Kyrghyzstan; to my good friend Leoscha Maslov, for sharing his knowledge of Islam with me, and putting me in touch with some fascinating people; and to Sergei Marcus, for introducing me to some wonderful Muslim contacts in Tatarstan and Dagestan. I would also like to thank each and every one of my interviewees for giving me their time so freely and generously: less than a third of their names appear in this book; as for the rest of them, many of their stories are still hibernating in my computer. Some of them have become good friends. I would especially like to thank Farit Valliulin from Kazan, Professor Magomed Ramazanov in Mahachkala, and Sirozhidin Abdusamatov from Fergana, whose hospitality and generosity were quite humbling.

A word on the genre of this book. Before starting this project, I had been working for several years on Russian religious thought, which is a peculiar genre that mixes philosophy, theology, journalism, and public advocacy. I had also been living in Moscow and working as a teacher at various universities and theological institutes. In that sense, I was rather removed from the typical article-writing, publish-or-perish environment of Western academia. When I got back from teaching at Dickinson, I went back to my previous teaching work in Moscow, and continued teaching on inter-religious dialogue seminars. As time went on, I also lent a hand to the Russian muftiats attempts to forge links with Western Muslims. My audience, as I came to see it, was thus not exclusively academic, and I had never intended the book to be a straight-forward scholarly history or sociological study of Russian Islam. Instead, that mixed genre of Russian religious thought has left its mark on me: theology, sociology, and personal travelogue all ended up blending into a narrative account of my investigations. My brief time at Dickinson was enough to show me that such a genre is absolutely forbidden within modern academia (at least for non-tenured scholars), but as an unaffiliated individual I saw no need to make greater claims to omniscience and objectivity than were warranted by my status. However, I am highly grateful to Michael Dwyer of Hurst for taking on board this somewhat unconventional offering. I would also like to thank Bruce Clark for reading a nearly complete version of the book before that, and reassuring me that it was indeed readable and informative. I would also like to thank Professor Timothy Winter of Cambridge University for reading a first draught, and for deepening my understanding of Islam. Inevitably, given the complex and controversial nature of the subject, there are places where I have undoubtedly been naive and perhaps eccentric in my evaluations; I hope specialists can forgive this, while those new to the subject will find something to take away.

Finally, I would like to thank my wife Maria for once again supporting me wholeheartedly. In my previous bookish endeavors, this has been limited to letting me keep my nose in my books, but this time she also went out on a limb by letting me take off for distant parts, sometimes at rather trying times. Heroism indeed!

Moscow has its own Islamic geography and toponymy; some of it is ancient and dormant, some of it has come to life again recently. The Zamoskvorechie, or Beyond-the-river, region lies across the Moskva river within sight of the red walls of the Kremlin. It is one of Moscows most picturesque and historic regions: the center of golden-domed Moscow; home to the world famous Tretyakov gallery; and dotted with sturdy merchant houses from the eighteenth centurya haunt for tourists and Muscovites alike soaking up their own past. But there are Islamic layerings to this past. The word Kremlin itself is a Tatar word meaning fortress. Two of the main streets in this beautiful district, are called Bolshaya Ordynka and Bolshaya Tatarskaya street. The word Ordynka derives from the Mongolian word orda, (camp, headquarters) and refers to the Golden Horde that ruled Muscovite Rus from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. The road heads south-east out of Moscow and used to link the Slavic capital with the Mongolian capital in Sarai, near the Caspian Sea. Bolshaya Tatarskaya, or Great Tatar street, recalls the districts long association with the various Tatar khanates; the embassies of the Nogai and Crimean khanates (the last to resist Russias imperial expansion into the Eurasian steppe) were situated here into the eighteenth century, and from early on a Tatar

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era»

Look at similar books to Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Russias Muslim Heartlands: Islam in the Putin Era and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.