4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

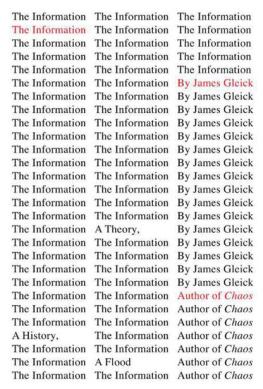

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

First published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, in 2016

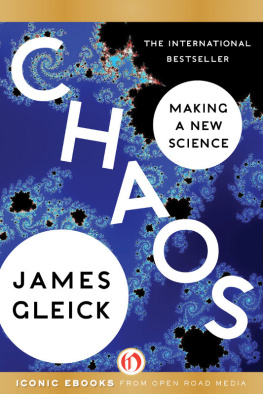

Text James Gleick 2016

James Gleick asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company for permission to reprint excerpts from Burnt Norton and The Dry Salvages from Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot, copyright 1936 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, renewed 1964 by T. S. Eliot, and renewed 1969 by Esme Valerie Eliot. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Grateful acknowledgment is also made to Faber & Faber Ltd for permission to reprint excerpts from Burnt Norton and The Dry Salvages from Four Quartets by T.S. Eliot. The Estate of T.S. Eliot. Reproduced by kind permission of Faber & Faber Ltd.

Cover photograph Bob Mawby/Shutterstock

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008207670

Ebook Edition September 2016 ISBN: 9780007544448

Version: 2017-08-25

To Beth, Donen,

and Harry

Your now is not my now; and again, your then is not my then; but my now may be your then, and vice versa. Whose head is competent to these things?

Charles Lamb (1817)

The fact that we occupy an ever larger place in Time is something that everybody feels.

Marcel Proust (1927?)

And tomorrow

Comes. Its a world. Its a way.

W. H. Auden (1936)

Contents

Being young, I was skeptical of the future, and saw it as a matter of potential only, a state of things that might or might not arise and probably never would.

John Banville (2012)

A MAN STANDS AT the end of a drafty corridor, a.k.a. the nineteenth century, and in the flickering light of an oil lamp examines a machine made of nickel and ivory, with brass rails and quartz rodsa squat, ugly contraption, somehow out of focus, not easy for the poor reader to visualize, despite the listing of parts and materials. Our hero fiddles with some screws, adds a drop of oil, and plants himself on the saddle. He grasps a lever with both hands. He is going on a journey. And by the way so are we. When he throws that lever, time breaks from its moorings.

The man is nondescript, almost devoid of featuresgrey eyes and a pale face and not much else. He lacks even a name. He is just the Time Traveller: for so it will be convenient to speak of him. Time and travel: no one had thought to join those words before now. And that machine? With its saddle and bars, its a fantasticated bicycle. The whole thing is the invention of a young enthusiast named Wells, who goes by his initials, H. G., because he thinks that sounds A proud member of the Cyclists Touring Club, he rides up and down the Thames valley on a forty-pounder with tubular frame and pneumatic tires, savoring the thrill of riding his machine: A memory of motion lingers in the muscles of your legs, and round and round they seem to go. At some point he sees a printed advertisement for a contraption called Hackers Home Bicycle: a stationary stand with rubber wheels to let a person pedal for exercise without going anywhere. Anywhere through space, that is. The wheels go round and time goes by.

The turn of the twentieth century loomeda calendar date with apocalyptic resonance. Albert Einstein was a boy at gymnasium in Munich. Not till 1908 would the Polish-German mathematician Hermann Minkowski announce his radical idea: Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality. H. G. Wells was there first, but unlike Minkowski, Wells was not trying to explain the universe. He was just trying to gin up a plausible-sounding plot device for a piece of fantastic storytelling.

Nowadays we voyage through time so easily and so well, in our dreams and in our art. Time travel feels like an ancient tradition, rooted in old mythologies, old as gods and dragons. It isnt. Though the ancients imagined immortality and rebirth and lands of the dead time machines were beyond their ken. Time travel is a fantasy of the modern era. When Wells in his lamp-lit room imagined a time machine, he also invented a new mode of thought.

Why not before? And why now?

THE TIME TRAVELLER BEGINS with a science lesson. Or is it just flummery? He gathers his friends around the drawing-room fire to explain that everything they know about time is wrong. They are stock characters from central casting: the Medical Man, the Psychologist, the Editor, the Journalist, the Silent Man, the Very Young Man, and the Provincial Mayor, plus everyones favorite straight man, an argumentative person with red hair named Filby.

You must follow me carefully, the Time Traveller instructs these stick figures. I shall have to controvert one or two ideas that are almost universally accepted. The geometry, for instance, that they taught you at school is founded on a misconception. School geometryEuclids geometryhad three dimensions, the ones we can see: length, width, and height.

Naturally they are dubious. The Time Traveller proceeds Socratically. He batters them with logic. They put up feeble resistance.

You know of course that a mathematical line, a line of thickness nil, has no real existence. They taught you that? Neither has a mathematical plane. These things are mere abstractions.

That is all right, said the Psychologist.

Nor, having only length, breadth, and thickness, can a cube have a real existence.

There I object, said Filby. Of course a solid body may exist. All real things

So most people think. But wait a moment. Can an instantaneous cube exist?

Dont follow you, said Filby [the poor sap].

Can a cube that does not last for any time at all, have a real existence?

Filby became pensive. Clearly, the Time Traveller proceeded, any real body must have extension in four directions: it must have Length, Breadth, Thickness, andDuration.

Aha! The fourth dimension. A few clever Continental mathematicians were already talking as though Euclids three dimensions were not the be-all and end-all. There was August Mbius, whose famous strip was a two-dimensional surface making a twist through the third dimension, and Felix Klein, whose loopy bottle implied a fourth; there were Gauss and Riemann and Lobachevsky, all thinking, as it were, outside the box. For geometers the fourth dimension was an unknown direction at right angles to all our known directions. Can anyone visualize that? What direction is it? Even in the seventeenth century, the English mathematician John Wallis, recognizing the algebraic possibility of higher dimensions, called them a Monster in Nature, less possible than a Chimaera or Centaure. More and more, though, mathematics found use for concepts that lacked physical meaning. They could play their parts in an abstract world without necessarily describing features of reality.