ALL THAT LIES BETWEEN US

ESSENTIAL POETS SERIES 153

MARIA MAZZIOTTI GILLAN

GUERNICA

TORONTO BUFFALO CHICAGO LANCASTER (U.K.) 2007

Copyright 2007, by Maria Mazziotti Gillan and Guernica Editions Inc. All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law.

Antonio DAlfonso, editor Guernica Editions Inc. P.O. Box 117, Station P, Toronto (ON), Canada M5S 2S6 2250 Military Road, Tonawanda, N.Y. 14150-6000 U.S.A.

Distributors: University of Toronto Press Distribution, 5201 Dufferin Street, Toronto (ON), Canada M3H 5T8 Gazelle Book Services, White Cross Mills, High Town, Lancaster LA1 4XS U.K. Independent Publishers Group, 814 N. Franklin Street, Chicago, Il. 60610 U.S.A.

First edition. Printed in Canada.

Legal Deposit First Quarter National Library of Canada Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006940788 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Gillan, Maria M. All that lies between us / Maria Mazziotti Gillan. (Essential poets series ; 153) ISBN 978-1-55071-261-2

9781550714708 epub

9781550714715 mobi

I. Title. II. Series. PS3557.I375A75 2007 811.54 C2006-907003-2

Contents

People Who Live Only in Photographs

Little House on the Prairie

What Did I Know About Love

The Mediterranean

Christmas Story

There Was No Pleasing My Mother

Breakfast at IHOP

I Want to Write a Poem to Celebrate

Superman

I Am Thinking of the Dress

My Fathers Fig Tree Grew in Hawthorne, New Jersey

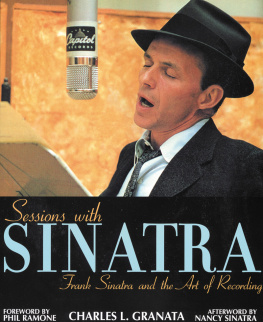

My Sister and Frank Sinatra

Sunday Dinners at My Mothers House

My Father Always Drove

Spike-Heels

Trying to Get You to Love Me

Housework and Buicks with Fins

Driving into Our New Lives

Nighties

In the Movies No One Ever Ages

Who Knew How Lonely the Truth Can Be

I Wish I Knew How to Tell You

What a Liar I Am

On an Outing to Cold Spring

Selective Memory

Your Voice on the Phone Wobbles

On Thanksgiving This Year

I Never Tell People

Do You Know What It Is I Feel?

What I Remember

I Walk Through the Rooms of Memory

Nothing Can Bring Back the Dead

What I Cant Face About Someone I Love

Is This the Way It Is with Mothers and Sons?

Everything We Dont Want Them to Know

At Eleven, My Granddaughter

My Daughters Hands

My Grandson and GI Joe

What We Pass On

The Dead Are Not Silent

What the Dead No Longer Need

I Want to Celebrate

Couch Buddha

People Who Live Only in Photographs

My mantle is lined with photographs of the dead; those people who live only in black and white. Their faces, serious and self-contained, watch sofas and chairs.

Denniss great-grandmother and great-grandfather stand in their Victorian wedding clothes: he, in his stiff high-necked shirt, black suit; she, in her high-necked gown, starched and pleated bodice, plumed hat. They are not smiling, but look prosperous and poised, a standard photo, circa 1892.

And here is Denniss father as a young man in his captains uniform, a Bing Crosby look-alike. He is pleased with himself and the world, next to my father at sixteen in his first posed photograph, proud and serious in his high-topped shoes, dark suit and white collar, a formal bouquet of flowers on the table. It is this photograph his mother carried until she died, though he left Italy when he was sixteen and never saw her again.

My grandmothers, whom I never met, stare out of inexpensive frames. Beside Denniss grandmothers, who sit stately in their sterling oval frames, look poor and worn.

Looking at them, these people I see every day, I think how little I know to tell a snippet of a story, a name nothing else. How little of their past we can pass on to our own children and grandchildren. My mother did piecework in a factory for fifty years, sewing sleeves in coats for a few cents apiece.

I tried to piece together the past of these people who exist now only in frames by asking questions, but there is no one left to ask.

I wrote poems about my children as they grew up, my mother and father, small bits I remembered about my grandparents. I think now these poems are photos of a past whose details otherwise no one would know.

Little House on the Prairie

After I found the Little House on the Prairie books in the Riverside branch of the Paterson Public Library, I read them all, my eyes moving fast across the page, and then read them all again, fascinated by the familys journey over mountains, across plains, admiring the courage it took to travel that huge emptiness to get to a place theyd never been,

while I sat in Mr. Landgraff s seventh grade at PS18 in Paterson; Mr. Landgraff who was sarcastic, mean, and handsome, in a white-haired, white-man kind of way. Mr. Landgraff who preferred the pretty charming girls. Mr. Landgraff who thought I was too introverted and shy. I dreamt my way through seventh grade, imagining myself in that covered wagon, though I hadnt left Paterson more than twice,

for in Little House I found the bravery I lacked, reading all evening at home and walking to school in the morning, sitting where Mr. Landgraff told me to sit, crushable as a caterpillar. But after he marked off my name in his attendance book, I floated off to Kansas and Nebraska, sure that, like Laura,

I could be brave, that there was a place out there where I could live a life as extraordinary and risky as any I read about in books, far removed from the chalk dust and quiet despair of seventh grade with its green black-out shades, its picture of George Washington, its scarred and battered desks that tried to hold me captive.

What Did I Know About Love

I was twelve. What did I know about love, about how I would love the boy who lived next door for being gentle and kind, for the way he always acted as if I were breakable and precious; someone to be guarded and cared for, though his father was a drunk who beat him up, and his mother was skinny with a cigarette always dangling from the corner of her mouth.

Where did he learn such tenderness? What un-smashed corner of himself carried this sweetness? I think of him sometimes, the first boy I ever loved, the one who would be the model of every man I ever fell for, with his golden hair, wide blue eyes, clear skin, the long delicate fingers of his hands, think and remember how wed walk home together

from PS 18 down the cracked and broken sidewalks of 19th Street. One night, his family moved out. One step ahead of the bill collectors, the neighbors said. I did not see him again, but I remember the way hed stop a minute at my house to watch me head toward our back stoop, and then hed turn, face his own house and hesitate, gathering himself to go inside.

The Mediterranean

At twenty-three, my mother followed my father to Paterson from San Mauro, that small town that clung to a mountaintop. From her window in that southern Italian village, she glimpsed the Mediterranean, glistening blue.

In the village, they heard stories of storms that rose from the sea, swallowed fishermen and boats. As a child, she heard them, but loved the sea anyway, her own secret jewel with its incredible light.

In Paterson, inside our tenement, my mother made the food shed grown up cooking, filled the house with the unforgettable aroma of Mediterranean cuisine, told us stories of San Mauro, the stone house

where she lived, the well where they drew their water, the stream where they washed their clothes, the fields built like steps up the sides of the mountain, but it was the sea she most remembered.