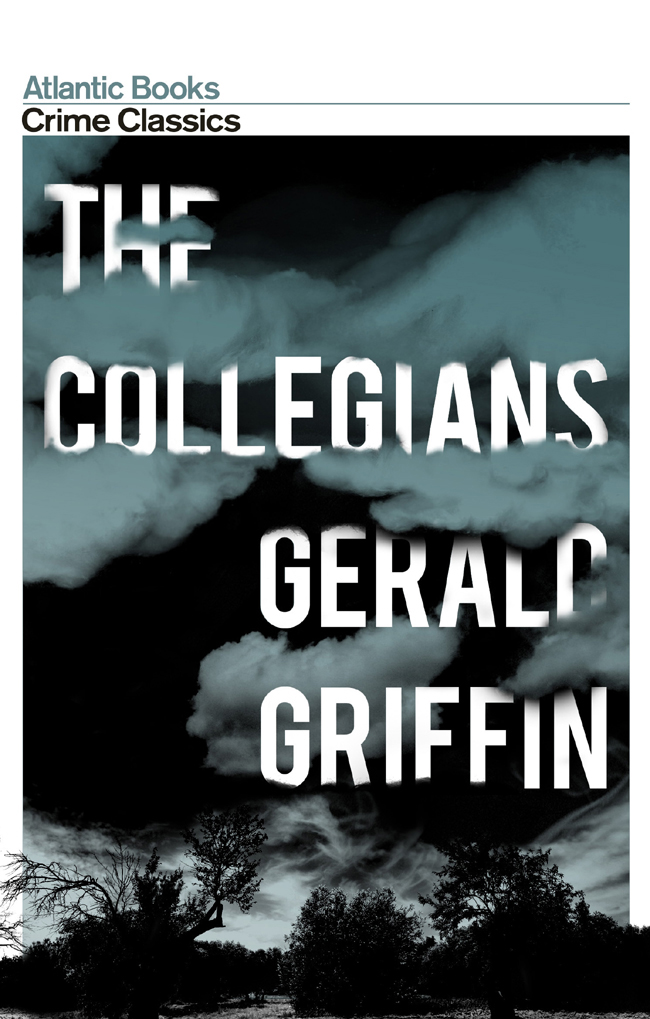

The Collegians

Gerald Griffin was born in Limerick, Ireland, in 1803. The son of a brewer, he first became a reporter and later turned to writing fiction. In 1838 he entered the Society of the Christian Brothers in Dublin to become a member of the teaching order. He died from typhus fever in 1940. For more information turn to the Case Notes section at the end of the book.

Robert Giddings is a literary critic and broadcaster who regularly writes for publications including the Tribune and the Dickensian. He is the author of A Students Guide to Charles Dickens, and co-author with Keith Selby of The Classic Serial on Television and Radio.

Other titles in the Crime Classics series

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

Bulldog Drummond by Sapper

Raffles by E. W. Hornung

The Man Who Was Thursday by G. K. Chesterton

Lady Audleys Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon

The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe

The Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers

Wylders Hand by Sheridan Le Fanu

Arthur Conan Doyles Favourite Holmes Mysteries

First published in Great Britain in three volumes in 1829.

This paperback Crime Classics edition published by Atlantic Books in 2008.

Case Notes copyright Robert Giddings, 2008

The moral right of Robert Giddings to be identified as the author of the afterword to this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84354 855 3

eISBN 978 1 78239 952 0

Series Consultant: Robert Giddings

Designed by Lucie Ewin

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Chapter 1

How Garryowen Rose, and How it Fell

THE little ruined outlet, which gives its name to one of the most popular national songs of Erin, is situate on the acclivity of a hill near the city of Limerick, commanding a not uninteresting view of that fine old town, with the noble stream that washes its battered towers, and a richly cultivated surrounding country. Tradition has preserved the occasion of its celebrity, and the origin of its name, which appears to be compounded of two Irish words signifying Owens garden. A person so called was the owner, about half a century since, of a cottage and plot of ground on this spot, which from its contiguity to the town, became a favourite holiday resort with the young citizens of both sexes a lounge presenting accommodations somewhat similar to those which are offered to the London mechanic by the Battersea tea-gardens. Owens garden was the general rendezvous for those who sought for simple amusement or for dissipation. The old people drank together under the shade of trees the young played at ball, goal, or other athletic exercises on the green; while a few lingering by the hedge-rows with their fair acquaintances, cheating the time with sounds less boisterous, indeed, but yet possessing their fascination also.

The festivities of our fathers, however, were frequently distinguished by so fierce a character of mirth, that, for any difference in the result of their convivial meetings, they mightas well have been pitched encounters. Owens garden was soon as famous for scenes of strife, as it was for mirth and humour; and broken heads became a staple article of manufacture in the neighbourhood.

This new feature in the diversions of the place, was encouraged by a number of young persons of a rank somewhat superior to that of the usual frequenters of the garden. They were the sons of the more respectable citizens, the merchants and wholesale traders of the city, just turned loose from school with a greater supply of animal spirits than they had wisdom to govern. Those young gentlemen, being fond of wit, amused themselves by forming parties at night, to wring the heads off all the geese, and the knockers off all the hall doors in the neighbourhood. They sometimes suffered their genius to soar as high as the breaking of a lamp, and even the demolition of a watchman; but perhaps this species of joking was found a little too serious to be repeated over frequently, for few achievements of so daring a violence are found amongst their records. They were obliged to content themselves with the less ambitious distinction of destroying the knockers and store-locks, annoying the peaceable inmates of the neighbouring houses with long continued assaults on the front doors, terrifying the quiet passengers with every species of insult and provocation, and indulging their fratricidal propensities against all the geese in Garryowen.

The fame of the Garryowen boys soon spread far and wide. Their deeds were celebrated by some inglorious minstrel of the day in that air which has since resounded over every quarter of the world; and even disputed the palm of national popularity with Patricks day. A string of jolly verses were appended to the tune which soon enjoyed a notoriety similar to that of the famous Lilli-burlero, bullen-a-la which sung King James out of his three kingdoms. The name of Garryowen was as well known as that of the Irish Numantium, Limerick, itself, and Owens little garden became almost a synonym for Ireland.

But that principle of existence which assigns to the life of man its periods of youth, maturity, and decay, has its analogy in the fate of villages, as in that of empires. Assyria fell, and so did Garryowen! Rome had its decline, and Garryowen was not immortal. Both are now an idle sound, with nothing but the recollections of old tradition to invest them with an interest. The still notorious suburb is little better than a heap of rubbish, where a number of smoked and mouldering walls, standing out from the masses of stone and mortar, indicate the position of a once populous row of dwelling houses. A few roofs yet remain unshaken, under which some impoverished families endeavour to work out a wretched subsistence by maintaining a species of huckster trade, by cobbling old shoes, and manufacturing ropes. A small rookery wearies the ears of the inhabitants at one end of the outlet, and a rope-walk which extends along the adjacent slope of Gallows Green (so called for certain reasons) brings to the mind of the conscious spectator associations that are not calculated to enliven the prospect. Neither is he thrown into a more jocular frame of mind as he picks his steps over the insulated paving stones that appear amid the green slough with which the street is deluged, and encounters at the other end an alley of coffin-makers shops, with a fever hospital on one side, and a churchyard on the other. A person who was bent on a journey to the other world could not desire a more expeditious outfit than Garryowen could now afford him: nor a more commodious choice of conveyances, from the machine on the slope above glanced at, to the pest-house at the farther end.

But it is ill talking lightly on a serious subject. The days of Garryowen are gone, like those of ancient Erin; and the feats of her once formidable heroes are nothing more than a winters evening tale. Owen is in his grave, and his garden looks dreary as a ruined church-yard. The greater number of his merry customers have followed him to a narrower play-ground, which, though not less crowded, affords less room for fun,and less opportunity for contention. The worm is here the reveller, the owl whoops out his defiance without an answer (save the echos), the best whiskey in Munster would not now drive the cold out of their hearts; and the withered old sexton is able to knock the bravest of them over the pate with impunity. A few perhaps may still remain to look back with a fond shame to the scene of their early follies, and to smile at the page in which those follies are recorded.