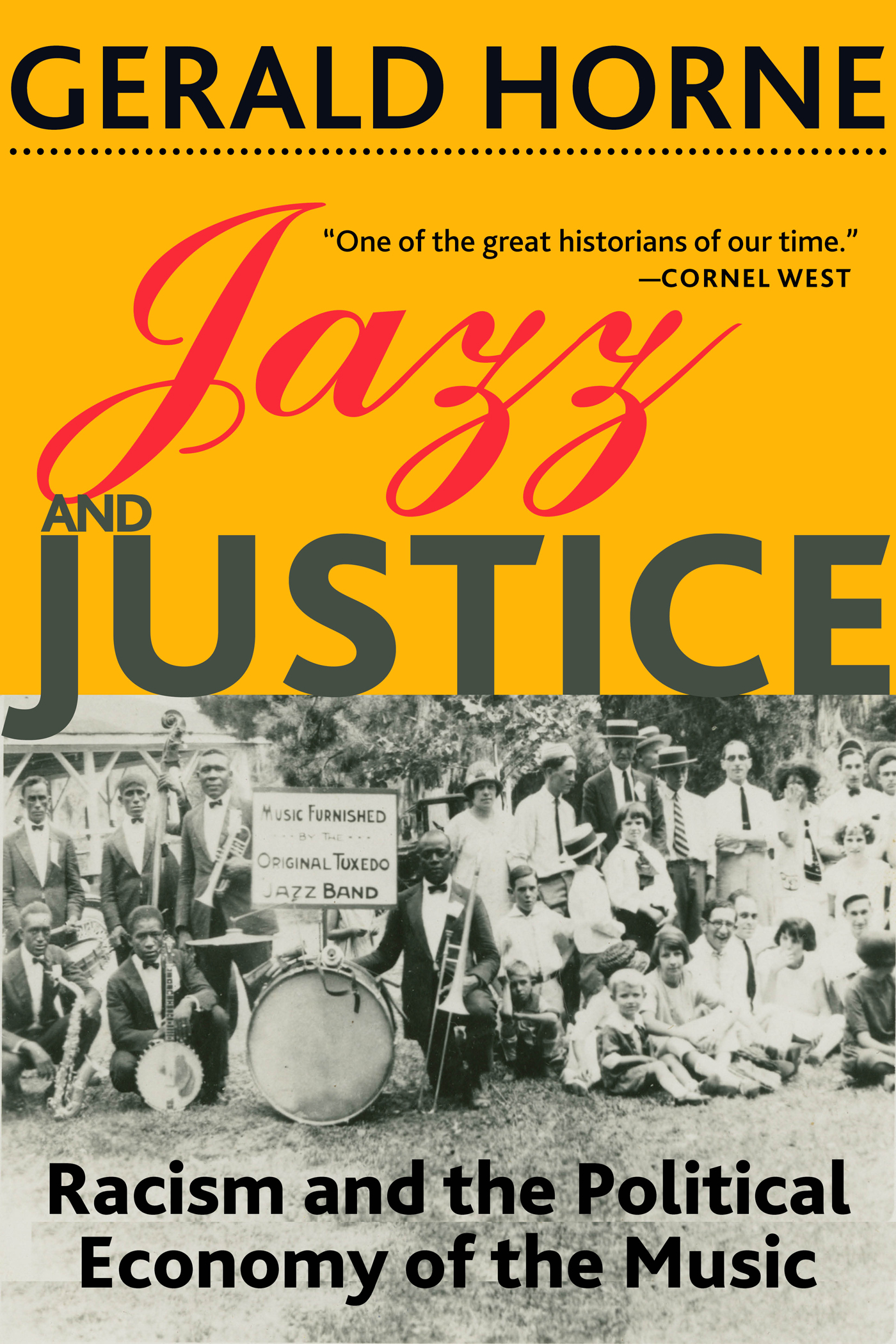

JAZZ AND JUSTICE

Jazz

and

JUSTICE

Racism and the Political Economy of the Music

GERALD HORNE

MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS

New York

Copyright 2019 by Gerald Horne

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Horne, Gerald, author.

Title: Jazz and justice : racism and the political economy of the music / Gerald Horne.

Description: New York : Monthly Review Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019017464 (print) | LCCN 2019017611 (ebook) | ISBN 9781583677872 (trade) | ISBN 9781583677889 (institutional) | ISBN 9781583677858 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781583677865 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Jazz Social aspects United States History. | Jazz--Political aspects United States History. | Music and race United States History. | Jazz musicians United States Social conditions. | Jazz musicians United States Economic conditions.

Classification: LCC ML3918.J39 (ebook) | LCC ML3918.J39 H67 2019 (print) | DDC 306.4/84250973 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019017464

Typeset in Minion Pro and Bliss

MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS, NEW YORK

monthlyreview.org

5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

BUCK CLAYTON WAS READY TO RUMBLE.

It was about 1934 and this Negro trumpeter found himself in Shanghai, a city on the cusp of being bombarded by marauding Japanese troops. But that was not his concern. Instead, what he thought he had escaped when he began performing in China had followed him across the Pacific Ocean. White guys [were] saying, he wrote decades later, there they are. Niggers, niggers, niggers! These incendiary epithets lit the fuse and soon fists were flying and when it was all over the Chinese onlookers treated us like we had done something that they had always wanted to do and followed us all the way home cheering us like a winning football team.

He may not have recognized it at the time of the fracas, but Claytons Asian encounter illustrated several themes that had ensnared Negro musicians, especially practitioners of the new art form called jazz. Often, they had to flee abroad, where they found more respect and an embrace of their talent. And often the sustenance found there allowed them to develop their art and sustain their loved ones. Overseas they were capable of fortifying the global trends that in the long run proved decisive in destroying slavery and eroding the Jim Crow that followed in its wake. Back home they were forced to fight to repel racist marauders, some of whom had hired them to perform.

A glimpse of this phenomenon was exposed when the Negro composer and musician Benny Carter arrived in Copenhagen as Clayton was being pummeled in Shanghai. When he exited the train, he was recognized as a celebrity. I was literally lifted onto the shoulders of people, he said decades later, and they carried me out of the station to a waiting automobile and I was taken to my hotel with this crowd behind. And I was really never so thrilled. He was stunned to ascertain that Europe was less racist toward those like himself in comparison to his homeland; in Europe he found acceptance of you just on the basis of you as a human being.

This is a book about the travails and triumphs of these talented musicians as they sought to make a living, at home and abroad, through dint of organizingand fighting. I approach this subject with a certain humility, well aware, as someone once said, that writing about music is like dancing about architecture, that is, using one artistic vocabulary to portray another is inherently perilous. The problem is that the historian thereby runs the risk of circulating misinformation, a prospect I will seek to evade in the pages that follow.

WHAT IS THIS MUSIC CALLED JAZZ? Why does it carry this name and where did it develop?

Jazz, according to the late Euro-American pianist, Dave Brubeck, speaking in 1950, was born in New Orleans about 1880 consisting of an improvised musical expression based on European harmony and African rhythms.

The subversive impact of this new form has been said to subvert racial segregation, musically enacting [an] assault on white purity, and the music was said to have encouraged racial boundary crossings by creating racially mixed spaces and racially impure music, both of which altered the racial identities of musicians and listeners.

Alert readers may have noticed that I have introduced the term jazz with a bodyguard of quotation marks. This is meant to signify the contested employment of this term. Thus the master percussionist

This music is said to have its roots in the Slave SouthNew Orleans more specifically. But even this, like the presence of Clayton in Shanghai, is contested. One analyst argues for a kind of candelabra theory of the origins of this music, arising simultaneously in various sites for similar reasons. Thus, like New Orleans, the San Francisco Bay Area had ties to a wider global community, meaning the influence of diverse musical trends and instruments, particularly opera and its Italian traditions, not to mention a bordello culture that provided opportunities to play. One of the many theories about the term jazz is that it originated in the early twentieth century among Negro musicians in the hilly fog-bound California metropolis.

Given that both St. Louis and New Orleans hugged the Mississippi River, where riverboats overflowing with performing musicians plied the muddy waters, it is possible that this new music developed

This music is also an offshoot of the music known as the blues, a product of those of African origin in Dixie, which expressed their hopes and pains: hence, one scholar has characterized the blues as a veritable epistemology.

Adding to a version of the candelabra theory of the origins of the music are the words of the legendary journalist J. A. Rogers, who argued that the roots of the music could be found in the Indian war dance, the highland fling, the Irish jig, the Cossack dance, the Spanish fandango, the Brazilian maxixie, the dance of the whirling dervish, the hula hula of the South Seasand the ragtime of the Negro.

Still, New Orleans claim as the seedbed of this music is bulwarked by the fact that the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War (18611865) and the onset of the War with Spain in 1898 with troops embarking and disembarking from the mouth of the Mississippi River, led to various musical instruments being snapped up by Africans, as military and naval bands dissolved. Moreover, by 1850 New Orleans was by some measures the bordello capital of the new Republic, leading to more cabarets, nightclubsmeaning more musicat a time when San Francisco was hardly an adolescent city.

On the other hand, one analyst claimed that Cuban nativesand not the New Orleans keyboardist Jelly Roll Morton who claimed parentagestarted jazz in 1712.

Whatever the case, it appears that the first authenticated appearance of the word jazz in print was, perhaps tellingly, in the San Francisco Call, on 6 March 1913.

In turn, the Negro composer Will Marion Cook is of the opinion that ragtime with its syncopated and ragged rhythm, which developed at the end of the nineteenth century, as U.S. imperialism began to extend its overseas reach, was shaped by the trips of Negro sojourners to ports in North Africa and western Asia dominated by the then Ottoman Empire.

Next page