Copyright 2008 by Thomas F. Flynn. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information, write Andrews McMeel Publishing, LLC, an Andrews McMeel Universal company, 1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flynn, Tom, 1946 Dec. 16

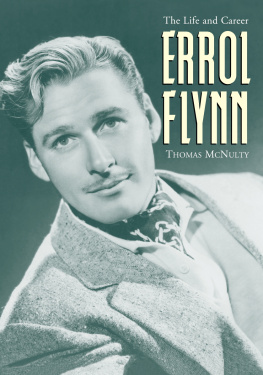

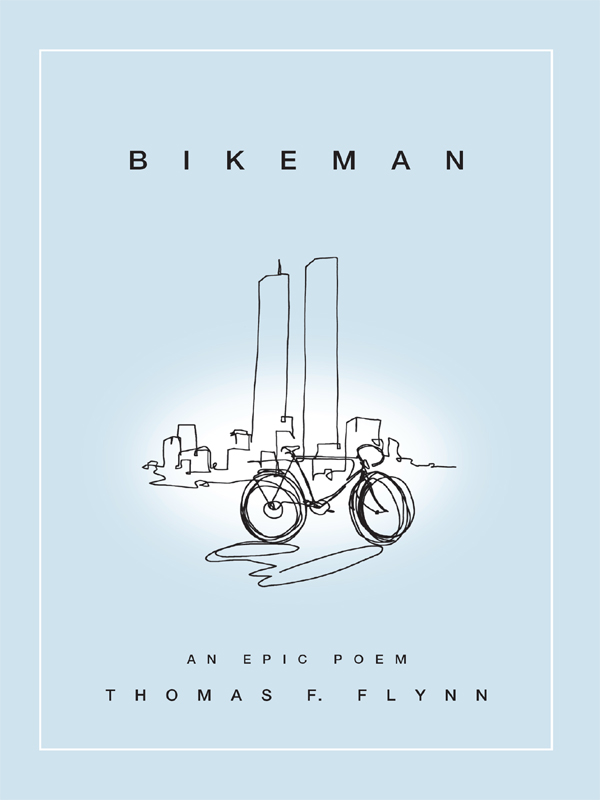

Bikeman / Tom Flynn.

p. cm.

E-ISBN: 978-0-7407-9026-3

1. September 11 Terrorist Attacks, 2001Personal narratives. I. Title.

HV6432.7.F585 2008

974.71044dc22 2007047269 www.andrewsmcmeel.com Design by Diane Marsh

Jacket Design by Tim Lynch

Illustration by Rachel Ann Lindsay ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND BUSINESSES

Andrews McMeel books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use.

For information, please write to: Special Sales Department, Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106.

DEDICATION

Dante, lucky fellow, had Beatrice as his companion in heaven. Ive been luckier. Nancys been mine on earth. This is dedicated to her and to Kate, the most wonderful daughter anywhere.

FOREWORD BY DAN RATHER

ON A WALK THROUGH NEW YORK not long ago, I saw a parked car wearing two of those ribbon magnets that have become so common in recent years. Instead of the more common Support the Troops, though, one ribbon bore the message 9-11; the other, Survivor.

In the nation at large, the visceral memories of September 11, 2001, have largely been replaced with symbolic representations of patriotism, sacrifice, and mourning. But here in the city where the towers once stood, although the memories have fadedas memories willthe rawness of direct experience remains at their core. New Yorkers do not remember that day as a collection of television and newsmagazine images. What we revisit in the theater of our minds are scenes recorded by our own eyes and ears. We saw, we heard, and, yes, we smelled and breathed the smoke and dust firsthand. There is a sense in which all of us who were in New York on that day the towers fell could be consideredand consider ourselvessurvivors.

The immediacy and accuracy of that feeling of having survived spreads in concentric circles from the point that, almost from the start, became known as Ground Zero. My own experience of that day played out on the far edges of an outer circle: An Upper East Side morning view of distant, smoldering towers; a series of phone calls; a quick trip across and downtown to a television news studio where I spent the next fourteen hours conveying what I could of what was happening in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania to a nation shocked and saddened. Throughout the day, my perch in the newsroom afforded me terrifying and bewildering views of what lay at the center of it all. They were views mediated by video cameras, microphones, and distance, but they carried a near-knockout force nonetheless. One on the periphery could only imagine the experience of those caught in the inner circles of that day. Imagine, and feel the shudder of fury and helplessness.

Tom Flynn, who worked with me then as a writer for CBS News, found himself pulled into the deepest rings of that hell, lured there by the reporters instinct and urge to bear witness. What he found when he arrived was an inferno on highand then the terrible descent of persons and of buildings, of every and all, the darkness and chaos of a midday night. Later in the day, when he made it uptown, he told some of his story to me on the air. The raw emotion in his voice was as real, as tangible as the dust still entangled in his hair, still smudged on his face. What Tom has set down here are the reports of the journalist as poet, or poet as journalist. The two are not so far apart as some may think, nor are the experiences limned in our cultural touchstones so far removed from our contemporary headlines.

These dispatches in verse tell the story of a journey into a modern underworld, and of the escape that made it possible to tell the tale. Here is a survivors lament, related by one who did not live through it but just did not die. Here is what remains in one man of what has become, for so many and despite the passage of years, that forever September morning. It is a harrowing document of what crumbles without and within, one that reverberates well after the reading.

Dan Rather New York City November 2007

AN INTRODUCTION TO BIKEMAN

TOM FLYNNS

BIKEMAN IS A VIVID, eyewitness account of the events at the World Trade Center immediately following the attack on the morning of September 11, 2001. Among the thousands of strange tales from that day, few are stranger than his.

Bikeman is no less striking in its form than in its content, for it is written in a kind of searing free verse that attempts to impose some discipline on raw emotion without denying its intensity.

Bikeman is no less striking in its form than in its content, for it is written in a kind of searing free verse that attempts to impose some discipline on raw emotion without denying its intensity.

Few readers will have encountered anything like Bikeman before. I myself, who have spent a lifetime reading poetry in its protean varieties, have not before encountered its like. An epic poem about 9/11? Except in a few limited venues, not always encouraging ones-song lyrics and greeting card verse come to mind-poetry has lost broad popular appeal. This is not the place to speculate as to why poetry in America has come to seem to the general reader, if that person still exists and still reads poetry at all, as academic and hierophantic. Perhaps it has something to do with contemporary poetrys excessively academic and hierophantic tendencies. What is particularly striking to any student of literary history is not that our age is an age of prose.

For that there are excellent explanations. But the demise of poetry is no necessary corollary of the primacy of prose. Why has our age so thoroughly marginalized poetry? The virtual disappearance of extended narrative poetry is especially baffling. At its heart literature is story, and from time immemorial those who wrote, recited, or repeated great stories sought the beauty, the dignity, the prestige of poetry in which to relate them. This is true in most of the worlds cultural traditions. In our own we got the famous stories of the Trojan War and the wanderings of Ulysses and the wanderings of neas.

So great was the association of poetry with story that form and content sometimes seemed inseparable. The Roman poet and literary critic Horace could actually suggest that the only appropriate subject of elevated poetry was the Trojan War. Bikeman, obviously, is about another war and another kind of war. The fiendishly improvised bombs that felled the Trade Center buildings were not the fatal beauty that burnt the topless towers of Ilium. But the two stories share more in common than death by falling rubble. Nor is narrative poetry restricted to the grandeur of the epic form or of high culture.

B I K E M A N

B I K E M A N