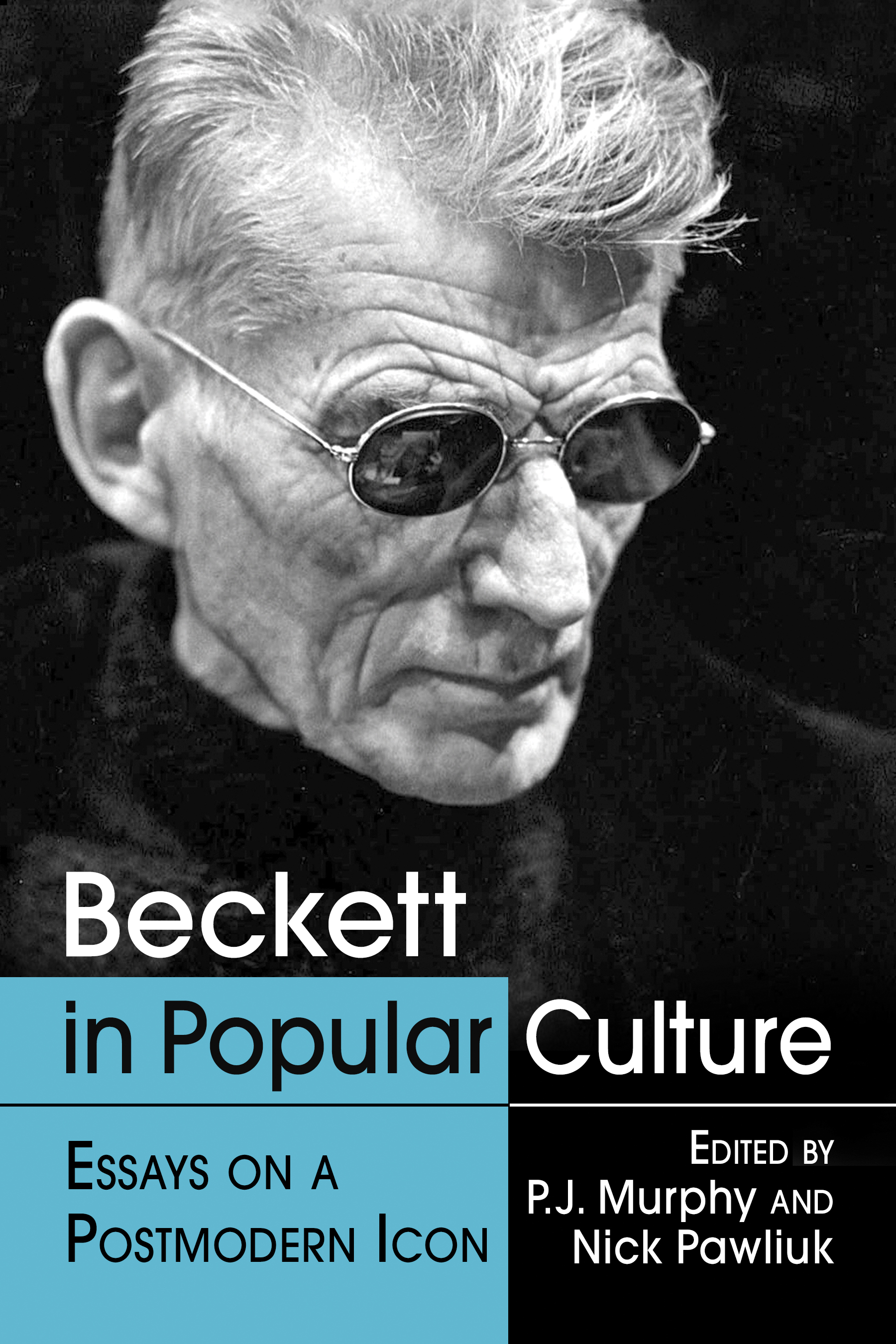

Beckett in Popular Culture

Essays on a Postmodern Icon

Edited by P.J. MURPHY

and NICK PAWLIUK

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2331-3

2016 P.J. Murphy and Nick Pawliuk. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Hes not fucking me about, hes not leading me up any garden, hes not slipping me any wink, hes not flogging me a remedy or a path or a revelation or a basinful of breadcrumbs, hes not selling me anything I dont want to buy, he doesnt give a bollock whether I buy or not, he hasnt got his hand over his heart. Well, Ill buy his goods, hook, line and sinker, because he leaves no stone unturned and no maggot lonely.

Harold Pinter (1967)

The postmodernisms have, in fact, been fascinated precisely by this whole degraded landscape of schlock and kitsch, of TV series and Readers Digest culture, of advertising and motels, of the late show and the grade-B Hollywood film, of so-called paraliterature, with its airport paperback categories of the gothic and the romance, the popular biography, the murder mystery, and the science fiction or fantasy novel: materials they no longer simply quote as a Joyce or a Mahler might have done, but incorporate into their very substance.

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism (1991)

A second constant has been a perhaps perverse de-hierarchizing impulse, a desire to challenge the explicitly and implicitly negative cultural evaluation of things like postmodernism, parody, and now, adaptation, which are seen as secondary and inferior.

Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Adaptation (2006)

But I like to think that all this hubbub of recombination [adaptations of all sorts] is, on balance, a healthy feature of any society that has a robust and living art and is busy arguing with itself on issues large and small. Viewed as such, the works of Beckett, along with what we think we know of Beckett himself, have become, and promise to continue to be, a powerful collection of instruments for art, thought, feeling, judgment, pleasure, and, yes, pain as well.

H. Porter Abbott, The Legacy of Samuel Beckett (2010)

Acknowledgments

Such a complex dialogical exchange as this book intends to be necessarily involves a number of other contributors in addition to the authors of the particular essays. Danielle ONeill sourced a multitude of Beckett in popular culture echoes and linkages. (Not to mention from her own eclectic reading, such as Dean Koontzs reference to a certain Mr. Godot, gun runner!) Jennifer Murphy and Tanya Pawliuk have over the years raised Beckett Spotting to an art formfrom cryptic crosswords to fashion magazines and points betwixt and beyond. Their insights have enriched our discussions of numerous points. Our former colleague Martin Whittles was a much appreciated collector of Beckettian references for us in magazines of all sorts, high and low. Our colleague Jeff McLaughlin, whose specialty is philosophy, comics, and the Holocaust, offered insightful suggestions on Beckett and the graphic novel. And, above all, Professor Werner Huber of the University of Vienna, who ever since our work together on Critique of Beckett Criticism: A Guide to Research in English, French, and German (1994), has supplied a series of on-going updates around the depiction of Beckett in popular culture, a veritable catalogue of Bakhtinian carnivalesque.

Preface

This project began with Nick Pawliuk proposing a sequel of sorts to my Becketts Dedalus: Dialogical Engagements with Joyce in Becketts Fiction (2009): namely, a study of popular culture adaptations of Becketts work which would in a number of ways complement how Becketts own work in some decisive ways was an adaptation of Joyces. We had both been collecting for ages (read decades) a host of Beckettian adaptations within popular culture and would periodically compare notes on the incredibly rich diversity of such materials and how they could sometimes shed new light on the so-called standard or accepted readings of Beckett. We realized that no such study of Becketts works in popular culture had as yet been undertaken and this was a decisive factor in our deliberations about proceeding with the project.

We began with a series of discussions about the theoretical framework and outlined an early version of what became the introductory essay: Saint Samuel () Becketts Big Toe: Incorporating Beckett in Popular Culture. The critical focus of our argument was a reassessment of a number of stereotypical assumptions about Beckett and his work. We thought that the shift in perspective afforded by popular culture could be especially productive in this rethinking, and combined we wrote two-thirds of the book. Our next strategic move was to recruit several colleagues with an abiding interest in adaptation theory as well as an extensive knowledge of Beckett: namely, Cameron Reid (modern film; pop music), Tanya Pawliuk (baby naming), Mark Rowell Wallin (social networking) and Alexander M. Forbes (short poems on images of Beckett in popular culture). (See About the Contributors for further background information on each author.) That none of them would claim to be a Beckett specialist per se worked to our advantage in that we asked them to examine afresh a number of popular culture adaptations of Beckett in specific areas and to evaluate the depiction of Beckett and his works in their commentaries.

Over the following three-year period, we held a series of informal seminar-type get-togethers (yes, a few pubs were necessarily pressed into service): various views about the overall development of the project were discussed and constructive criticisms offered about the essay topics we had commissioned. The one major exception was Nick Pawliuks recruitment of Stephen Brown, University of Ulster marketing guru, who generously allowed us to reprint his informative and provocative Fail Better! Samuel Becketts Secrets of Business and Branding Success, which is virtually unknown in Beckett studies and merits a new hearing.

We hope this foundational study will stimulate seminal questions about Becketts works and new ways in which we might approach them and adapt them.

Saint Samuel () Becketts Big Toe

Incorporating Beckett in Popular Culture

P.J. MURPHY

At the end of his inconclusive journey in search of his mother, Molloy invokes Chaucers General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales, citing a spring day replete with showers and bird melody; but whereas Chaucers characters longen then to goon pilgramages, Molloy longed to go back into the forest. Oh not a real longing. Of course not: at this stage of the game, it can be nothing but a literary longing. Molloys first memory after noting the birds music is of the two travelers A and C, perhaps as signs of Author and Character functions, both roles having been played by himself, as necessarily required by the doubling inherent in the re-presentation of narrative.

Next page