Contents

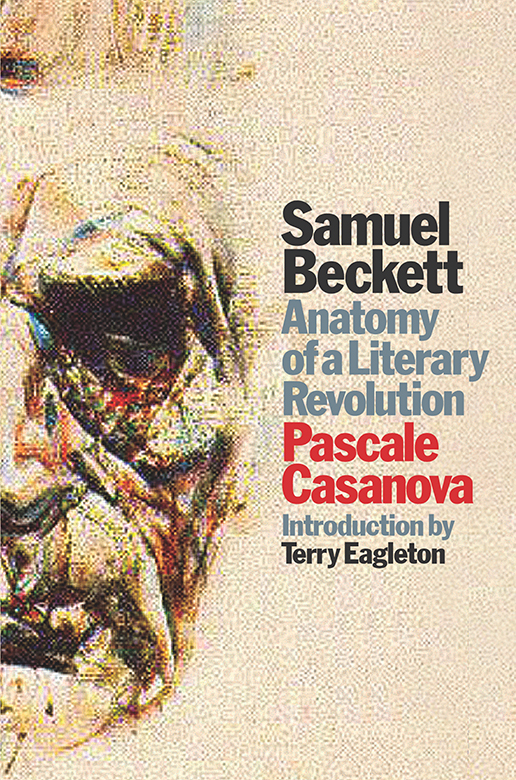

Samuel Beckett

Anatomy of a Literary Revolution

Samuel Beckett

Anatomy of a Literary Revolution

Pascale Casanova

Translated by Gregory Elliott

This edition published by Verso 2006

Verso 2006

Translation Gregory Elliott 2006

Introduction Terry Eagleton 2006

First published as Beckett labstracteur. Anatomie dune rvolution littraire

Editions du Seuil 1997

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-112-0

ISBN-10: 1-84467-112-7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Bembo by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the USA by Quebecor World

Contents

Samuel Beckett is one of those writers about whom almost nobody nowadays has a bad word to say, despite the fact that the first London production of Waiting for Godot was greeted with outraged cries of This is how we lost the Empire! Yet this well-nigh universal approval may not be entirely for the right reasons. Becketts work is undoubtedly somewhat bleak for the taste of a middle class which has traditionally required its art to be edifying; but it seems on the other hand so exactly the kind of thing the middle class expects its modern art to be namely, a tolerably obscure investigation of the human condition that its gloom may be largely forgiven. In any case, there are always critics on hand to scour these remorselessly negative texts for the occasional glimmer of humanistic hope, in a world where rank pessimism is felt to be somehow ideologically subversive.

Becketts prose is so palpably universal, so packed with pregnant lines, half-symbols and cryptic allusions, and his drama is so much the sort of thing that the West End theatregoer confidently expects from his evening out, that one wonders whether this stark, gratifyingly deep discourse of Man is not at some level as mischievously parodic as the work of his fellow Dubliner Oscar Wilde, who in poker-faced style turned out drawing-room dramas so impeccably well-made that they deferred to the English at the very moment they sent them up.

This existential-cum-metaphysical Beckett, resonant with the pathos of Being, may be a character dear to the heart of Maurice Blanchot, who figures more or less as the villain of this book; but it is far from the astonishingly revolutionary artist that Pascale Casanova presents us with here. This is a Beckett who pursues the logic of abstraction to its most inhuman extremes; who refuses the morphine of idealism even when in severe pain; whose work represents a merciless onslaught on the pretensions of Literature; and who preserves a compact with silence, breakdown and failure in the face of historical triumphalism and the self-flaunting word. As Casanova points out, he is out to dismantle the very conventional conditions of possibility of literature: the subject, memory, imagination, narration, character, psychology, space and time What else is his drama Breath but a response to the question: How can you write a play with no dialogue, scenery, plot, action or character? As for his world view, it is not out of the question that Beckett himself, despite his lugubrious oeuvre, might have been in private life a sentimental optimist with a Panglossian faith in human nature. We know enough of his life, in fact, to know that he was nothing of the kind; not many Panglossian optimists have landed up on the couch of the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion. Yet it is worth keeping the possibility in mind, just to remind ourselves of this authors aversion to the idea that he was somehow expressing himself in his writings. Even if anything as inconceivable as expression is going on, what is being expressed is certainly nothing as drearily pass as a self.

His work, in short, presents us with the scandal of a literature which no longer depends on a philosophy of the subject. The deflation of the rhetoric of achievement, along with the puristic horror of deceit which knows itself even so to be unavoidably mystified: this is no mere purveying of a way of seeing, but the stamp of a dissident, peripheral author who never ceases to shrink, mechanize and hack to the bone a twentieth-century world swollen with its own ideological bombast. It is no wonder he was such a fan of the evacuative aesthetics of his fellow Dubliner Jonathan Swift. For this politics of lessness, texts which only just manage to exist, statements which evaporate the very instant they flicker ambiguously up, break fewer bones than the declarations of a jiinger or a Heidegger. If Beckett was a great anti-fascist writer, it is not only because he fought with the French Resistance, a bravery for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre, but because every sentence of his writing keeps faith with power-lessness. The sheer contingency of his prose cuts the ground from beneath the sense of destiny and absolute certitudes of his political enemy. Even his decision to write in French, as Casanova points out, was influenced by his sense that French represented a form of weakness compared with the opulence of his native tongue.

This, as Adorno recognized, is partly a question of how to write after Auschwitz. Yet it also belongs to a specifically Irish legacy. Like Heraclitus, the Irish have always held that nothing is quite as real as nothing. Medieval Irish theology, with its emphasis on the frailty and littleness of Jesus rather than the august majesty of God the Father, preserves a certain minimalist style, while the greatest of all Irish medieval philosophers, John Scotus Eriugena, was Europes most subtle expounder of negative theology in the tradition of Pseudo-Dionysius, teaching the doctrine that God is non-being. Irelands most eminent modern philosopher, George Berkeley, remarked that for us Irish, something and nothing are near allied, while his clerical colleague Archbishop King of Dublin wrote that all finite beings partake of nothing, and are nothing beyond their bounds. The Tipperary-born novelist Laurence Sterne put in a word for nothingness, considering, he observed, what worse things there are in the world. For the aesthetician Edmund Burke, as well as for the novelist Flann OBrien, sublimity includes that which is barely visible as well as the immense and immeasurable, since both are equally ungraspable.

In modern times, these claims for the value of the negative, lowly or humbly unremarkable have a political resonance to them often enough. If Britain is very much something, then colonial Ireland is next to nothing. This inconsiderable afterthought of Europe, as Joyce scornfully dubbed it, was too small to give birth to the prodigal, capacious, ambitiously totalizing fictions of a Balzac or a Dickens. Instead, the short story became one of its most successful genres, pivoting as it does on a caught moment, isolated selfhood or stray epiphany. One of the nations premier short story writers, Sean OFaolain, felt that Ireland was too thin a society, too lacking in complex social machinery, to be fit meat for novelistic fiction. Henry James thought something rather similar about his native United States. If Joyce produced a monstrous tome in