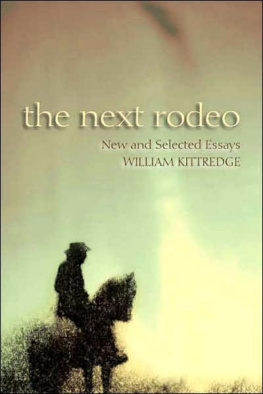

WILLIAM KITTREDGE

The NATURE of GENEROSITY

William Kittredge is the author of Hole in the Sky; Owning It All, a book of essays; and the story collections The Van Gogh Field and We Are Not in This Together. With Annick Smith, he edited The Last Best Place: A Montana Anthology.

ALSO BY WILLIAM KITTREDGE

Hole in the Sky

The Van Gogh Field and Other Stories

We Are Not in This Together

Owning It All

The Last Best Place: A Montana Anthology

Edited by William Kittredge (with Annick Smith)

VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION

VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION

Copyright 2000 by William Kittredge

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2000.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Departures and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Owing to limitations of space, all permissions to reprint previously published material can be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kittredge, William.

The nature of generosity / William Kittredge.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76584-0

1. Kittredge, WilliamJourneys. 2. Authors, American 20th centuryBiography. 3. Social ecology. 4. Human ecology. 5. Altruism. I. Title.

PS 3561. I 87 Z 472 2001

813.54dc21

[B]

2001026038

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

The Imperishable World

SOMETIME in the early 1880s, a medical doctor named Israel Wood Powell, superintendent for Indian Affairs for Coastal Indians in British Columbia, collected a raven rattle from the Tsimshian Indians. He sent the rattle to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where it remains today.

A percussive musical instrument used in elaborate ceremonial dances, this simple rattle resembles the ones we all shook in childhood, except that it is carved into the form of a mythological raven caught in the act of stealing the sun back from captivity, carrying the little red ball of the sun in his mouth, preparing to spit it back home into the heavens.

This is a striking idea, but not half so remarkable as the beings we see riding on the raven: a human figure reclining in a posture of sexual openness, and a frog crouched over, as if preparing to mount. Their tongues, in a slender red arc, form a single tongue as it reaches from human to frog and frog to human. In this vision, we share tongues with animals in some perfect sexuality while our trickster raven redeploys the sun.

See, that raven rattle says, this is how we are, inextricably one with everything, however tricked, riding, in fact, on the back of trickiness itself.

JUST ABOVE Elliott Bay in Seattle, in the public market, farmers wash leeks and radishes. Fish merchants sell crabs from seawater tanks. The air stinks of loam and oceans, the stench as wholesome as musk from a bed where a baby is at its mothers breast.

North of here, on the British Columbian coast, Prince Rupert is a colonial town with wide, clean streets and European gardens like something out of the nineteenth century. When I was there, a great storm rolled in off the Pacific. My true companion, Annick Smith, and I walked the beach beside the red cedar forest, a cold mist spraying over us from the dark rocks as ravens danced along on the power lines above the totem poles, mocking usas if trying to tell us that the world makes sense without us, in ways we are unlikely to understand.

Dempsey Bob, when we met decades ago (I know nothing of his life since), carved and sold traditional masks of great-eyed bears and ravens. He showed us how he did his work, uncovering a face hidden in the sweet red wood with one precise incision and then another. When I asked how he knew when a mask was finished, he said, When they start lookin back. This had the sound of a line tailor-made for tourists.

Reefs of wild roses bloomed under the cottonwoods. Upstream on either side of the Skeena River, which at that high-water stage looked wide as the Columbia, the stony, snowy peaks stood like boundary markers. Beyond lay the unroaded rain forests where Dempsey Bob had come to believe in his masks (if he really did and wasnt just kidding). At twilight, traveling through thickets of aspen along a feeder creek, we came to the village of Kitwancool, where we first saw the door pole called Hole in the Sky, which was thought to mark an entry into that particular heaven in which all the people we loved are still alive and somehow kicking.

Alongside it was a pole called All Frogs, erected in celebration of a native clan. Here, the carvers had re-created the beginning of things, a world of great frogs, four of them leaving the hands of a deity who revered them, the mother at the top and her young climbing down the red-cedar pole toward earth.

Meanwhile, all over the earth, frog populations are dying after surviving extinctions that killed off the dinosaurs. Maybe the cause is solar radiation leaking through our infamous holes in the ozone layer, or parasitesor both, or neither.

The point is, not many people have the will to care. The Greek word tragos means goat, and oide means song. Tragedies are goat songs, hymns to our fate as animals on earth. But many of us despise our animal natures. Many of us think its too late for nature, and others think that dying out is what we deserve. Maybe we should pull up our socks and just dance those blues away.

IN LATE SUNLIGHT on a hot May afternoon, I sauntered ( la Whitman) down Broadway toward Prince Street in Manhattans SoHo district and was struck by happiness. The streets were crowded by people seeming to represent every racial mix and continent and subcontinent, many of them talking in tongues, so far as I could tell, sometimes singing in any one of a multitude of languages I couldnt place. So much humanity, with the old boy, myself, idling among them in the maze of ornate brickwork walls, the heat rising from the reach of Broadway to the south. I wanted to think that one silver-haired young couple in matching lavender shorts were Icelandic; maybe theyd come to this city in search of gloryor sin, having had enough of glorious, silent ice fields.

In the 1950s, as I grew up in the backlands of the American West, we didnt believe in escaping to cities. Since our people had gone west looking for some version of freedom, we learned to despise cities as the native homes of injustice, or so we understood; yet look at me now, at ease with myself in this urban mix.

I was happy inside this downtown, our ancient, thronging situation. Every story adds to the stock of metaphors that is our actuality. This is why our lives seem so double- and triple-heartedat least that many hearts, given so many stories. We are creatures who have evolved with other creatures, whether ants, calling birds, charismatic lions, milk cows, gorillas, or one another. Nature and neighborhoods are versions of the same thing, our common homeland.

VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION

VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION