The text is packed with fascinating clues to life in the Celtic past gleaned from traditional cultural practices and changing place names. His new common-sense deductions are combined with succinct coverage of the documentary and archaeological evidence. Those who have read other books on Arthur will find a new dimension here. Readers new to the subject should find that the book provides a vivid and thought-provoking case for the Scots

Birmingham Evening Mail

Adding flesh to conjectures is an enjoyable thing to do and Moffat adds more flesh than most

Glasgow Herald

[Alistair Moffats] book, guaranteed to get up many noses, is to be recommended

Spectator

Fascinating It is great fun and a worthy addition to the enormous canon of Arthuriana

Daily Post (Wales)

This book is a virtuoso performance, packing in an astonishing amount of information on a wide range of subjects. I found his description of the British-speaking Celts of his part of Scotland, their customs and beliefs, entirely convincing. And he manages to bring them to life more vividly than any author I can remember

Cardiff Western Mail

Alistair Moffat was born and bred in the Scottish Borders. A former Director of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and Director of Programmes at Scottish Television, he now runs the Borders and Lennoxlove book festivals as well as a production company based near Selkirk. He is also author of a number of best-selling books. In 2011 he was elected Rector of St Andrews University.

This ebook edition published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

This edition first published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited

First published in 1999 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Copyright Alistair Moffat 1999 and 2012

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-226-9

ISBN: 978-1-78027-079-1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ILLUSTRATIONS

The aerial survey of the Roxburgh site is reproduced by permission of HMSO. The other photographs are by Ken MacGregor.

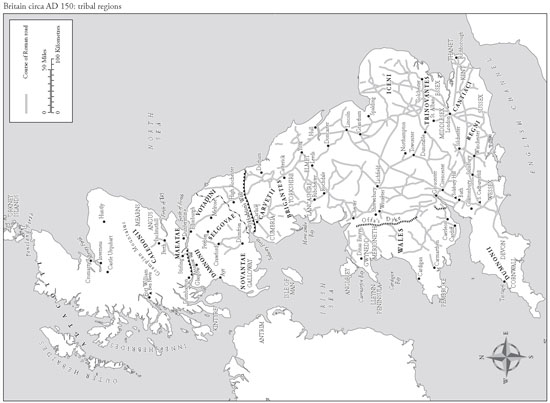

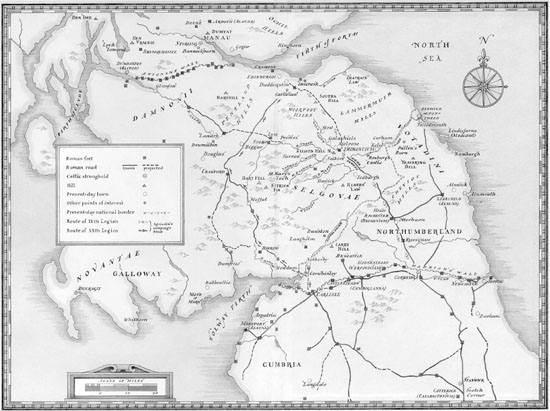

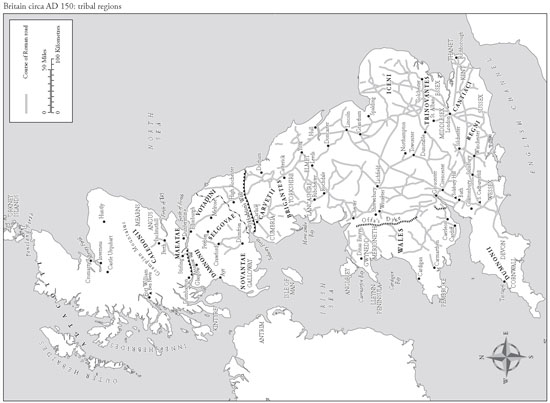

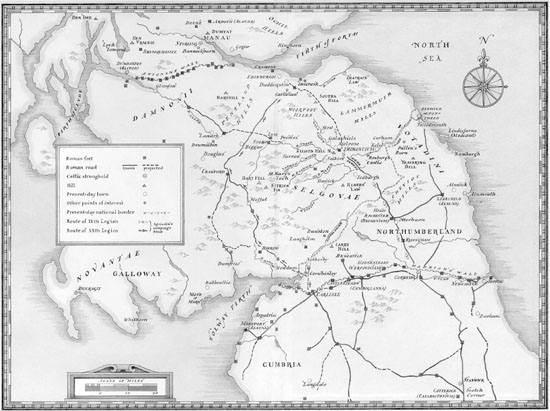

MAPS

LINE DRAWINGS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book has been forming for so long in my mind that it is difficult to remember some of the early kindnesses shown by people whose knowledge far outran my own. But I cannot forget how important my father, Jack Moffat, was in developing my own interest in the history of the Scottish Border country and in particular in place names. As much for his own amusement as anything didactic, he used to muse on names out loud, turning them over and over to get at what they meant. In every sense he made me think about these things before I passed them by. I owe him a debt of love that I can only repay to his grandchildren, and this book is dedicated to them.

Walter Elliot is a kenspeckle figure whose visceral and intellectual knowledge of the Borders is encyclopaedic. By an entirely different route he arrived at precisely the same conclusion as I did, and I am grateful for his kindness in sharing what he knows, and for reading this manuscript. He thoughtfully corrected some blunders but any inaccuracies that remain are entirely my own.

David Godwin should have been a farmer such is his ability to distinguish wheat from chaff. For his good humour, kindness and enthusiasm I am very grateful. Benjamin Buchan edited this book with tact and a sure touch, while Anthony Cheetham published it with brio and no little bravery.

No one helped me more in the process of writing this than Eileen Hunter. She showed me a path through the wilderness of word processing and made my life much easier. And as I navigated through options, files, tools and the rest, she kept me on the straight and narrow more than a few times. Many thanks and much love, Eileen.

My old friend George Rosie has borne several monologues on car journeys from Glasgow to Edinburgh with great fortitude, and his excellent film Men of the North for S4C and Scottish Television was partly a product of conversations on the M8.

To my Welsh-speaking friends I owe thanks for honest answers to puzzling questions and to Iain Taylor and Rhoda Macdonald more gratitude for wisdom and guidance in Gaelic. I hope none of them wince when they see passages from their beautiful mother-tongues rendered down into mine.

Harriet Buckley drew the illustrations for this book with patience and skill and also according to my suggestions. Therefore all that is good-looking about her drawings redounds to Harriets credit and any mistakes originate with me. Ken MacGregor is an accomplished documentary film-maker as well as an excellent photographer, and several of his pictures are worth more than several thousands of my words.

Finally I want to acknowledge the tolerance of my family. I am glad that while I was writing this my wife Lindsay, and our children Adam, Helen and Beth, had other lives which they allowed me to visit when it suited me.

Alistair Moffat

Selkirk, 1999

To Adam, Helen and Beth with all my love

1

ANOTHER RIVER

This is a story of Britain; a tale of the events and circumstances that first defined Britishness, resisted homogeneity and made these islands a collection of nations whose languages have survived to describe several versions of our present, and remember a past different from the one we think we know. It is also the story of a time when written memory fails us and when archaeology is imprecise; what historians have called our Dark Ages.

This is the story of Arthur; perhaps the most famous story we tell ourselves, certainly the most mysterious and least historical. He was a heroic figure who cast a mighty shadow over our history, colouring our sense of ourselves more deeply than any other. And yet he is elusive, barely recorded on paper or vellum and certainly not noted in the chronicles of his enemies, those who eventually won the War for Britain. But Arthur touched the landscape, and it remembered him.

That is where I came across his story, in the hills and valleys of Britain. At first I did not realize what I was looking at. When I began thinking seriously about this book, what I had in mind was something quite different. Originally I intended a miniature. Richly decorated, vividly coloured, pungent and full of interest perhaps, but a miniature for all that.

I was born and brought up in Kelso, a small town in the Scottish Border country and, quite simply, I wanted to write a history of the place because it will always mean home for me and the sight of it still warms me even after thirty years of absence. I had no ambition past capturing something of the essence of Kelso by setting down in reasonable order a chronicle of the years of its existence.

But almost as soon as I began my research, a series of unexpected and puzzling questions threatened to detour my straightforward purpose. Kelso first comes on written record in 1128 when monastic clerks drew up the abbeys foundation charter. All of the villages, churches and farms detailed in the document must have been going concerns well before that date, and so I set about finding earlier references to the town and its hinterland. Scottish medieval records are notoriously scant but I was still surprised at the paucity of material. I could find only one mention of Kelso before 1128 in any sort of document at all. This was an English translation of a poem written in Edinburgh around 600. Not in Gaelic as you might ignorantly expect, or Latin, but in an ancient form of Welsh. Known as The Gododdin it tells the story of the warriors of King Mynyddawg and their disastrous expedition to fight the Angles at Catterick in North Yorkshire. One of the Gododdin princes is named as Catrawt of Calchvyndd. I realized immediately that this is the oldest name for Kelso and also its derivation. In Old Welsh, Calchvyndd means chalky height and not only is part of the town built on such an outcrop but the street leading to it bears a translation, the Scots name Chalkheugh Terrace. And in the 1128 charter Kelso is spelled Calchou. Calchvyndd and Kelso are clearly the same place.

Next page