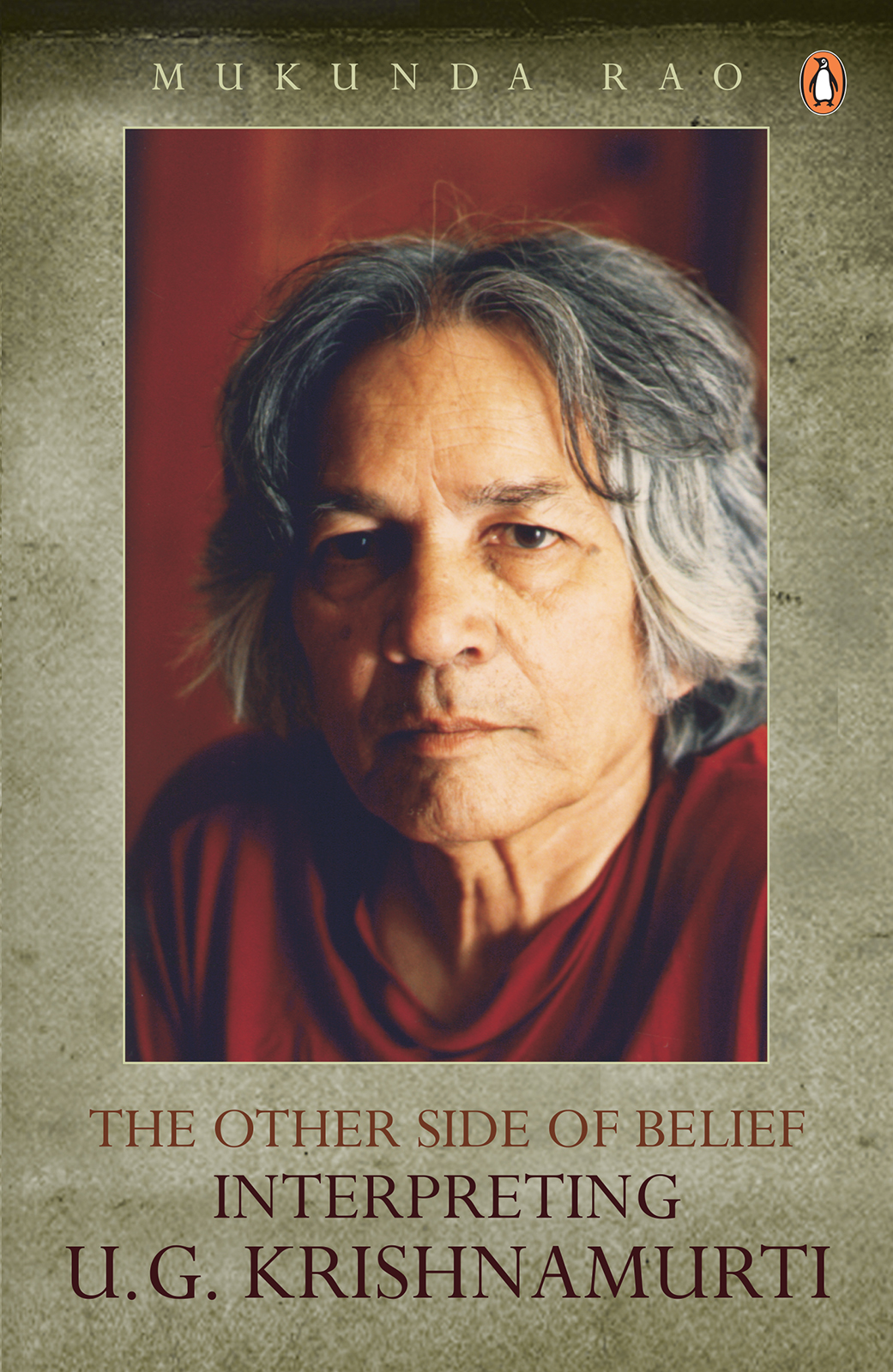

Mukunda Rao teaches English at Dr. Ambedkar Degree College, Bangalore. He is the author of Confessions of a Sannyasi (1988), The Mahatma: A Novel (1992), The Death of an Activist (1997), Babasaheb Ambedkar: Trials with Truth (2000), Rama Revisited and Other Stories (2002) and Chinnamanis World (2003).

He lives with his wife and son in Bangalore.

Foreword

T he story of mans relentless pursuit to understand the secret of existence is timeless. Trapped between a dead past and an unborn future, the human animal has, since the dawn of time, asked these two questionsWho am I? and Why am I here? These are the questions which propelled the author to the doors of the most subversive man in human historyU.G. Krishnamurti. And the outcome of that encounter is this exceptional book.

This book stands alongside others that have dealt with the history of mans search for an enduring truth. However, I would like to venture a word of caution... by the time you have flipped through the first few pages of the book you will realize that the author is making you look at the human situation through the eyes of a man who has torn down every sacred institution built by human thought, brick by brick, over the centuries.

We humans are burdened with a kind of consciousness that insists on our having a goal. That is why we yearn for stories which provide us with a sense of eternal meaning. No wonder stories which construct ideas prescribe rules of conduct and specify a social clout have been enshrined in our consciousness. The construction of narrative is a most important business of our species.

In this book, however, the author tells you the story of a story-buster, one who mocks, contradicts, rebuts, and has nothing but contempt for our universal stories. Nobody loves a story-buster... not unless the old story is replaced with a new one. Much of our ancient history concerns the punishment inflicted on those who challenged the existing narratives. Jesus was nailed to the cross, Socrates was forcibly given hemlock. The great story-busters Darwin, Marx and Freud were anything but lovable to the mass of people whose time-honoured narratives they attacked. There is nothing lovable about the hard-heartedness spouted by UGit infuriates and stuns the reader.

But strangely, as you read page after page, anecdote after anecdote, this book has a cleansing effect. It challenges the status quo, exploring the lives of individuals through the history of mankind, from Socrates and Nietzsche, to J. Krishnamurthy, who have all played vibrant roles in the continuous evolution of human values and culture.

Ranging from UGs encounter with the sage of Thiruvanamalai, whom UG met at the restless age of twenty-one, to his fierce runins with the messiah of the twentieth century, J. Krishnamurthy, who left an indelible mark on world culture the book is full of intimate anecdotes that enrich you with invaluable wisdom. To me it is indispensable, not because it shows where we have been, and where we are going, but because the author unflinchingly deals with the extreme grief of the loss of his daughter Shruti, who died in a road accident. The dignity with which he climbs out of this bottomless abyss, the way in which he grapples with the irreversibility of death and the question of afterlife, humble you. After the death of his daughter, when the author met UG unexpectedly, UG asked him a simple question with a gentle smile, How old was she when she died?thereby hurling him into the eye of the storm that was raging inside him. She was twenty-one he replied, and stopped there. But what he wanted to say was that Shruti was a rebel, that she was not in awe of her mothers social activism and feminism or her fathers philosophy, which she thought were shamsno different from the stupid conservatives, whom they often criticized.

This book fills you with a sense of reverence and passion for life because of the authors ability to connect with his pain, confront it and have the courage to live through it. It is his pain as well as the universal fear of loss, which we all dread so much, that gives him the ability to connect with the reader. We understand that it is the transient and ephemeral nature of life that makes it so precious. It is death that heightens the experience of life and makes us value it even more. For me, he says it all when he says Shrutis life was like UGs smile... brief, but warm, very warm, and enigmatic too.

Mahesh Bhatt

{1}

Prelude

A fter a lapse of nearly twelve years, I finally went to see U.G. Krishnamurti again in January 2002. Every year the news of the arrival of this strange bird in constant flight in Bangalore would somehow reach me, but I wouldnt feel the urge or curiosity to go and see him. There seemed no need to go and greet him or listen to his reproaches. But then, I would also tell myself: hasnt he become a part of me, a vital part of my consciousness? Is there really any way of getting away from him?

Perhaps there was another reason for not having kept in touch with him. Maybe I was afraid! I had had enough of himenough of these two Krishnamurtis. If J. Krishnamurti had tried to skew my spiritual search and puncture my hope of attaining moksha, UG had destroyed the very ground on which I had still been struggling to carry on my search somehow. There seemed no point to it at all. It was all futile. This search, this yearning, almost literally like searching for a needle in a haystack, or like looking for a black cat in a dark room, or was it more like chasing ones own shadow? It was not just unproductive or uncreative, it seemed positively harmful.

I cant help you, UG had warned again and again. Nobody can help you, and you cant help yourself either. In fact, there is nothing there to search for, to attain, he had added. And then finally, destroying all hopes, he had warned yet again: Your very attempt to become something which you are not is what makes your life miserable. Your very search for freedom creates its opposite and takes you away from it, that is, if there is such a thing as freedom at all.

Indian spiritual traditions teach that not by wealth, not by progeny, but by renunciation alone is immortality attained, and you are advised that renunciation can be taken up after completing the life of a student and a householder. However, Yagnavalkya says in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad that the very day when one becomes indifferent to the world (samsara) or comes upon a sense of disgust with life and the world, one should leave and become an ascetic.

Even as a student I had felt this disgust. I was not even twenty, but I had already started thinking of myself as a spiritual person born for higher goals. I spent most of my time outside the classroom, in public libraries and at the Ramakrishna Ashram library situated near my college, studying religious texts and the lives of spiritual masters, and again in the evenings, at home, I would immerse myself in reading or making notes from religious books. Since ours was a large family of five brothers and a sister, and there was hardly any quiet corner to meditate, I would sit in the open field in front of our house and meditate as long as I could, or gaze upon the heavens until tears streamed out of my eyes.