Table of Contents

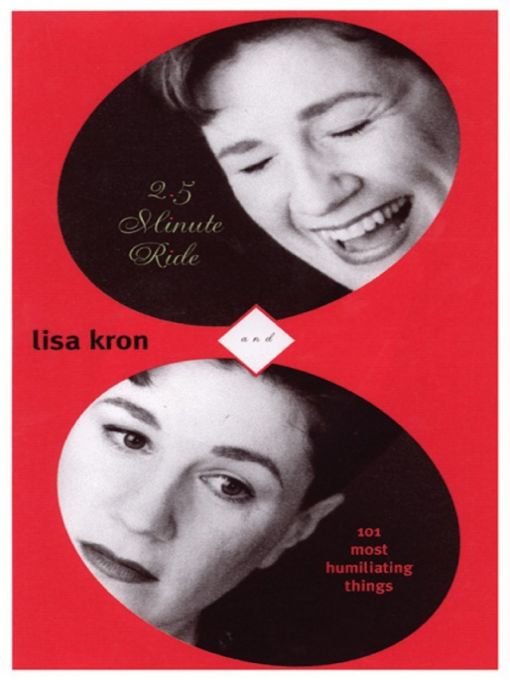

For my family who generously let me use their lives and havent yet disowned me.

For The Five Lesbian Brothers who took me apart and put me back together as a better actor and something closer to a writer.

Most especially for Peg Healeywho has given me the gift of true devotion as well as all of the best ideas.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the East Village performance spaces that existed in the mid-1980s where I wandered into a career as a solo performerin particular, the W.O.W. Caf, my home for many years; Dixon Place, where all my shows have been nurtured through their babyhoods; and Performance Space 122, which gave me my first longer runs and a professional step up.

Thanks to all at International Production Associates who kept faith in me and my work even when no one was booking it.

Thanks to New York Theatre Workshopa true creative home; Michael Grief and the La Jolla Playhouse who took a chance on 2.5 Minute Ride based on a twenty-minute reading; David Binder who, with great generosity, made it possible for me to rework the show in front of a New York audience; and The Joseph Papp Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival who gave the show the production I had dreamed of.

Most especially I thank Lowry Marshall who collaborated on the development of 2.5 Minute Ride and Jamie Leo who collaborated on the development of 101 Humiliating Stories. Both of them pushed me to do better work than I had done before, and each piece bears the imprint of their insight and considerable talents.

Introduction

My early solo shows were compilations of strung together anecdotes, low-rent versions of big musical numbers along with character bits and some short comic pieces made with film and slides. Two goals fueled this work, one was to really understand how to make an audience laugh. The other was to fully exploit and enjoy the development of my persona as a glamorous, all-singing, all-dancing lesbian ingenuea possibility which was opened to me at the W.O.W. Caf, that hotbed of sexy lesbian performance, and which had most definitely not existed in college or in the mainstream professional world where I was firmly put in my place by the label: character actress.

After some years as the lesbian Lola Falana, as I called myself at that time, I was yearning to make work that would still be entertaining but would also have shape and resonance. I wanted to make solo work that would also be theater. It seemed to me that there were two rules I would have to follow to accomplish this. First, the goal of autobiographical material should not be to tell stories about yourself but, instead, to use the details of your own life to illuminate or explore something more universal. Second, the work should not merely be a series of recollections. There has to be a dynamic elementdramatic action and conflict. Something must happen in the course of the performance.

The greatest skill I have developed as a solo performer, and the one that has brought me the most joy, is my ability to speak directly to an audienceto draw on that energy an audience feels when they realize something is actually happening right now, tonight, in this very room. It is my goal to strive for total fluidity so that my performances expand and contract to incorporate any unexpected intrusionslike the ringing of a cell phone, or a particularly noticeable reaction. I dont want the audience to feel they are watching something that is going to play out the same way with or without them. Instead I want them to feel they are seeing something happen in this very momentwith them and because of them.

So it was natural, as I developed the two pieces that follow, that I would find the action of these plays in the very act of attempting to tell a story. And the conflict in each piece would be the derailing of the storys planned course, resulting in what appears to be a completely unanticipated revelation.

Each play employs a metaphorical devise which develops the conflict. In 101 Humiliating Stories it is the overlay of the high school reunion (suggested to me by my partner Peg Healey, and developed by Jamie Leo). The phoned-in invitation to perform at this event sets in motion four speeches given to the class of 1979, which seem to bubble up from a subconscious well of anxiety tapped into by the very thought of revisiting high school. In 2.5 Minute Ride, the slides (also suggested by Peg) serve as the catalyst. The journey taken in the piece reflects the six-year journey I took in creating it. I start out with the goal of telling the story of my fathers life and experience, thus fulfilling my self-imposed duty as the witness and preserver of his lost world. In the telling, it begins to dawn on me that this is not a duty I can fulfill. The slides take on a life of their own and bring me to a broken-down place where I am entirely unmoored for a long, horrible moment until, out of this crisis, something new and unexpected surges out of me.

These two pieces differ in content, but they are alike in that they both seek out the awkward moment. They dwell in discomfort. It is here that humor can be found, of course, and it also allows for the exploration of great feeling while avoiding sentimentality. The work seeks the places where we stumble, where we are derailed by awkwardness, grandiosity, pretentiousness, vanity. It looks for the humanity lurking in the crevices of human behavior, and in so doing, creates a bond that makes room for certain assumptions to be challenged.

101 Humiliating Stories is not about me being a lesbian. But that was the assumption many of the audiences made upon first hearing me utter the L word. One of the delights of performing the show was feeling a house full of regional theatre subscribers travel from fearthat they were about to be harangued by a big, heavy-handed, man-hating messageto a surprised sense of identification and connection.

2.5 Minute Ride deals with the Holocausta subject an audience approaches with a tremendous amount of emotional assumption. It seems to me that in this age of Holocaust museums and memorials we have developed a way of responding to this most horrible of tragedies that, in fact, protects us from ever approaching its horror. We come to it with a prescribed attitude of reverence and awe. We know the outcome. We feel grief for the victims and heap shame on the perpetratorsand we feel secure in our ability to discern one from the other. As I considered my fathers history, one of the things I became fascinated with was the difference between the stories describing the events of the Holocaust, and what it must have been like to actually experience those events.

Stories, of course, have a shape and a context. They are made up of elements handpicked from chaos to form sense. Life as we are living it has no shape. Its a matter of one foot in front of the other, with a very limited side-to-side view and no clear picture at all of what lies ahead. In any given moment were likely to be driven by both our most generous selves and our most petty impulses. In

For my family who generously let me use their lives and havent yet disowned me.

For my family who generously let me use their lives and havent yet disowned me. For The Five Lesbian Brothers who took me apart and put me back together as a better actor and something closer to a writer.

For The Five Lesbian Brothers who took me apart and put me back together as a better actor and something closer to a writer. Most especially for Peg Healeywho has given me the gift of true devotion as well as all of the best ideas.

Most especially for Peg Healeywho has given me the gift of true devotion as well as all of the best ideas.