"I have decided to consider it all just a terrible mistake," I told my integrator, "and the best thing to do is to simply ignore it and get on with my life."

The integrator looked at me with large and lambent eyes. It had been eating its way through yet another bowl of expensive fruit and did not pause in its chewing as it said, "That may be difficult to do."

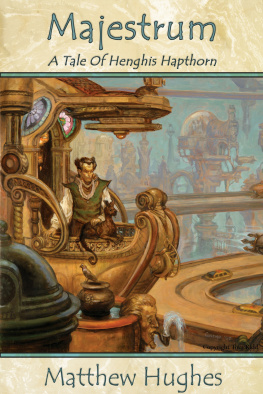

Its voice came, as always, from some indefinite point in the air. It occurred to me, and not for the first time, to wonder how it contrived to still speak in that manner. A few days before I could have drawn a schematic to show exactly how its collection of interconnected components worked. I had, after all, assembled and disposed them in various locations about my workroom, so that I would have a research and communications assistant equipped with all the appropriate skills and systems that a freelance discriminator required. It had been a more than acceptable device and over the many years of our association it had become, as the best integrators did, almost an extension of my own well calibrated mind.

But that was before a series of exposures to interdimensional forces and -- though it galled me to admit it, there was no other word -- "magic" had transformed my assistant into an undefined species of creature for which, again, the only accurate term was a "familiar." It now spent much of its day on my table, reflexively grooming itself and dining on rare fruits that would not have been out of place in the breakfast room of one of Olkney's wealthiest magnates. It ordered the delicacies delivered from suppliers, charging them to my account. When not eating or grooming, it slept.

"It may be difficult to do," I said, "but I believe that I am equal to the task."

"Will you cease to see me?" it said. "Will you dismiss me as a hallucination?"

I had anticipated the objection. "I will have a suitable dwelling made for you. It can go in the corner over there. From the outside it will look like a chest or gardrobe."

"You mean to put me in a cage?" The glossy brown hair on the back of its neck rose like a ruff.

"That implies confinement," I said. "My intent relates more to concealment. I do not wish to have to explain you to visitors." Indeed, I was not sure I could offer a convincing explanation without giving rise to gossip; as Old Earth's foremost freelance discriminator I was, after all, a well recognized figure in Olkney.

"I am less interested in your intent than with the outcome," it said. "I ask again: am I to be caged?"

I pointed out that when it was a disseminated device, it did not mind being decanted into a portable armature that fitted over my neck and shoulders so that it could accompany me when I traveled. I had been wearing the integrator in that fashion when we had passed through a contingent dimension to escape from an otherwise permanent confinement that would have eventually proved fatal. It was after we reemerged into my workroom that I found my assistant transformed.

"It is different now," it said, and chose a purple beebleberry from the bowl. "I am not what I was. Things are not what they were."

"That is the part I will not accept," I said, raising a hand and ticking off one finger as I continued. "Granted, though I inveighed against its partisans for years, I must now accept there is such a thing as magic. I waive all my former objections. It cannot be said that Henghis Hapthorn cannot swallow reality, however bitter the taste."

I addressed another digit. "Granted, also, that for some unfathomable reason, from time to time rationality recedes and magic..."

"Sympathetic association is the preferred term," my integrator said.

I inclined my head. "Very well, rationality bids the cosmos farewell and sympathetic association advances to claim the territory. I have accepted that as well."

"How gracious of you," it said.

I ignored the tone and I seized a third extremity, giving it a portentous waggle as I said, "But -- and this is a but of great pertinence -- the salient point is that the grand cycle has not yet reached the cusp of transposition. A new age of sympathetic association certainly approaches, its shadow occludes the doorway, but it is not yet here ."

My integrator extended a longish pink tongue and licked the juice from its small, fur covered hands while its voice came from the air to point out that some elements of the coming age had, in fact, arrived early -- a diminutive thumb pointed back at its glossy chest -- and must be dealt with.

"Ah," I said, "but that is merely one way of looking at the situation. Another way is to note that the premature arrival was an accident, simply the outcome of a few odd twists of circumstance, so why don't we just ignore them and get on with more important concerns?"

"Have you considered the possibility that our standards as to what is important may differ?"

"I will make accommodations," I said. "Fruit will be provided."

It was difficult to read a set of features that blended the feline with the simian, but I thought to see a look of relief flit across its furred visage. Then its expression went suddenly blank; I had lately learned to associate this neutral face with the integrator's performance of its communications function, and was not surprised when it announced that it was receiving an incoming signal from its counterpart at The Braid, Lord Afre's country house, inquiring if I was available to speak.

"Say that I will be presently," I said. I went to a wall cabinet and brought forth a cincture of woven metallic fibers; I bound it around my skull so that a lozenge fixed to its mid point was centered on my forehead. The small plaque was inlaid with the insignia of a honorary rank that had been bestowed on me by the Archon Dezendah Vesh some years before, in gratitude for discreet services.

I signaled to my integrator that I was ready. Instantly, a screen appeared in the air before me and, a moment later, it filled with the aristocrat's elongated face. His abstracted gaze seemed to slide over me as if unable to get a grip, then managed to achieve focus. It was to assist Lord Afre's perception that I had donned the Archonate token. Members of the uppermost strata of Old Earth's human aristocracy had, over the millennia, become increasingly attuned to such symbols. They could see rank quite clearly, and could perceive details of clothing and accessories so long as they were fashionable. Persons who possessed neither title nor office often found it difficult to attract and hold their attention, although their household servants were able to do so by adopting specific postures and gestures while wearing livery.

Afre's pale and narrow lips parted, permitting a few words to escape in the drawl that was fashionable among the upper reaches of Olkney society. "Hapthorn? That you?"

"It is," I said.

"Henghis Hapthorn, is it?"

"Indeed."

"The discriminator?"

"The same."

"I want to talk to you."

"Very well. Please do so."

"Not this way. Come to The Braid."

"My I ask what would be the subject of our conversation?" I had found that, when dealing with the highest echelons, it could be wise to delineate the situation in advance. Early in my career I had been called to the residence of the Honorable Omer Teyshack and kept waiting several hours, only to be asked to give my opinion on the merits of double-tied neckwear versus those of the single-knotted. The lordling and his cousin, the Honorable Esballine Teyshack, had disagreed over the issue, had wagered on the outcome and, in need of a neutral judge to adjudicate the question, had elected to summon me. I had been annoyed at the time but had consoled myself afterwards by reflecting that I had learned a useful lesson for future dealings with such folk. The disputants also having neglected to ask my fee in advance, I was further comforted by presenting them with an extravagant bill.

Next page