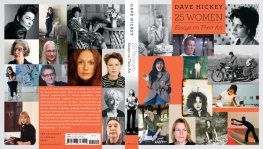

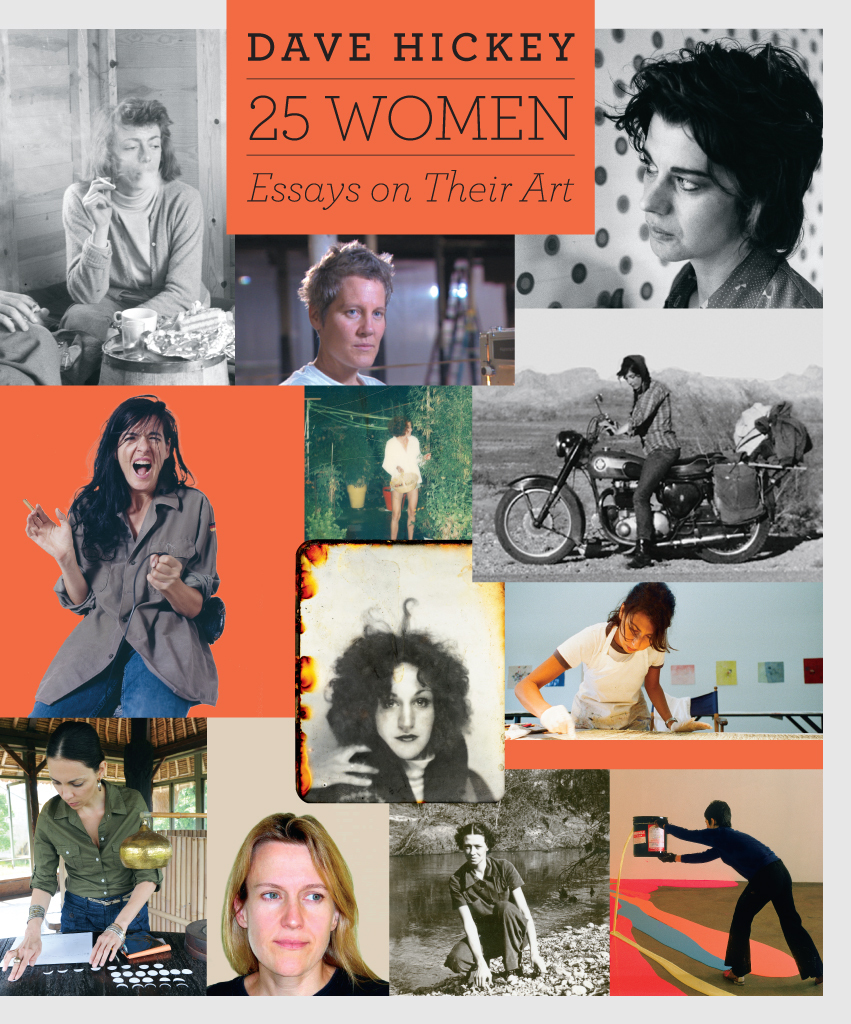

25 Women

Essays on Their Art

Dave Hickey

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

DAVE HICKEY is former executive editor of Art in America and the author of The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty and Air Guitar. He has served as a contributing editor for the Village Voice and as the arts editor of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by Dave Hickey

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in China

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-33315-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24914-8 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226249148.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hickey, Dave, 1940 author.

25 women : essays on their art / Dave Hickey.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-226-33315-1 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-24914-8 (ebook) 1. Women artists. 2. Art criticism. I. Title. II. Title: Twenty-five women.

N8354.H53 2015

704.042dc23

2015009740

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

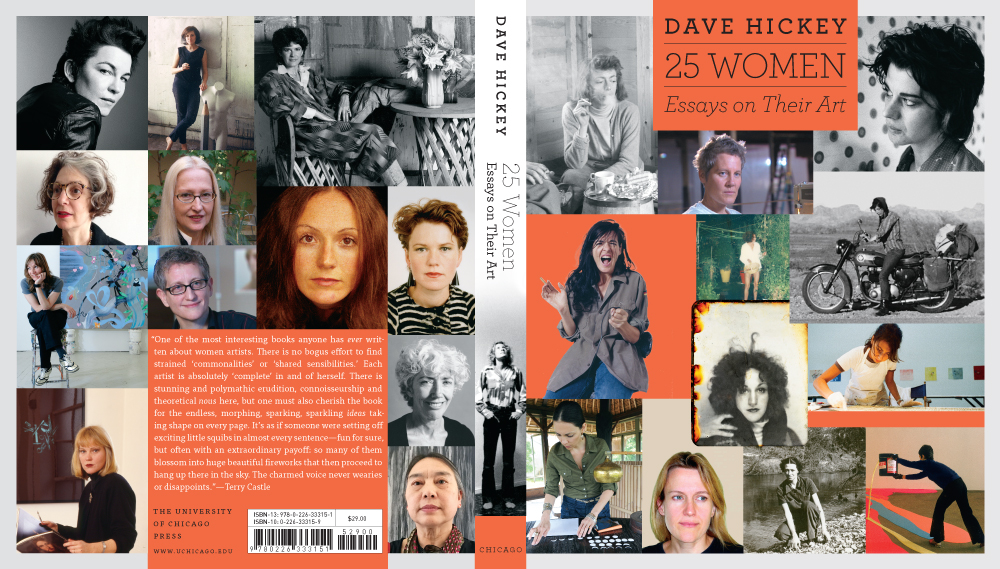

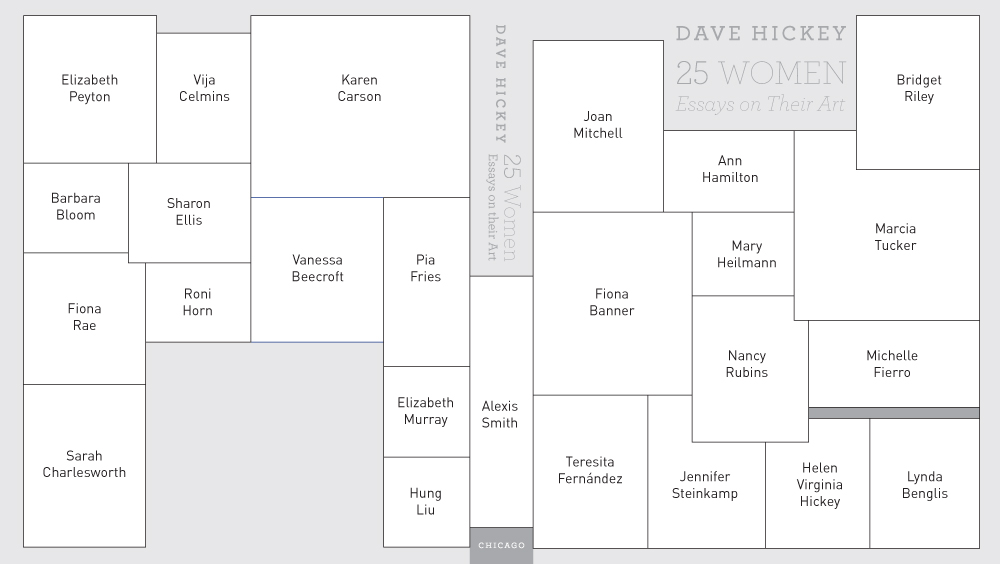

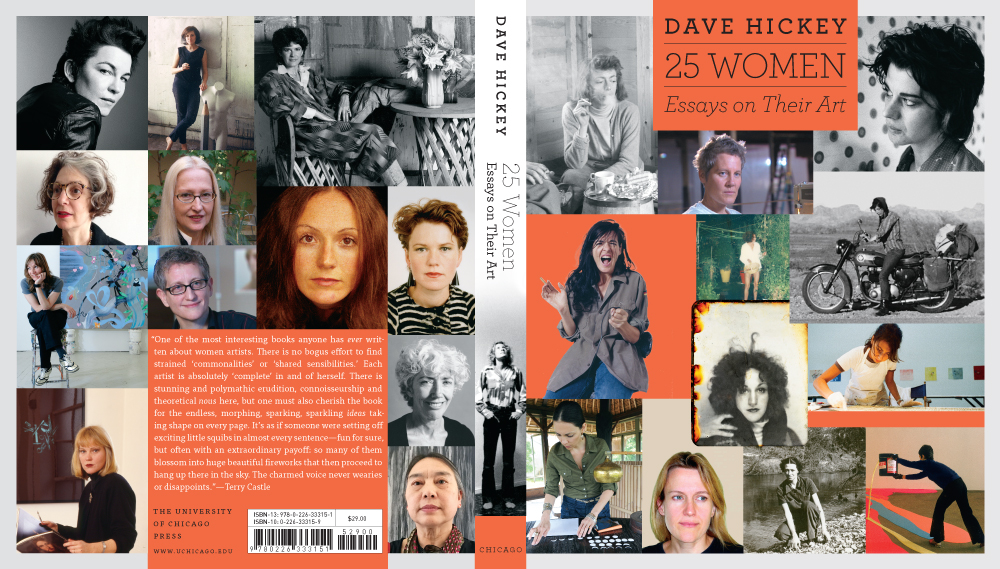

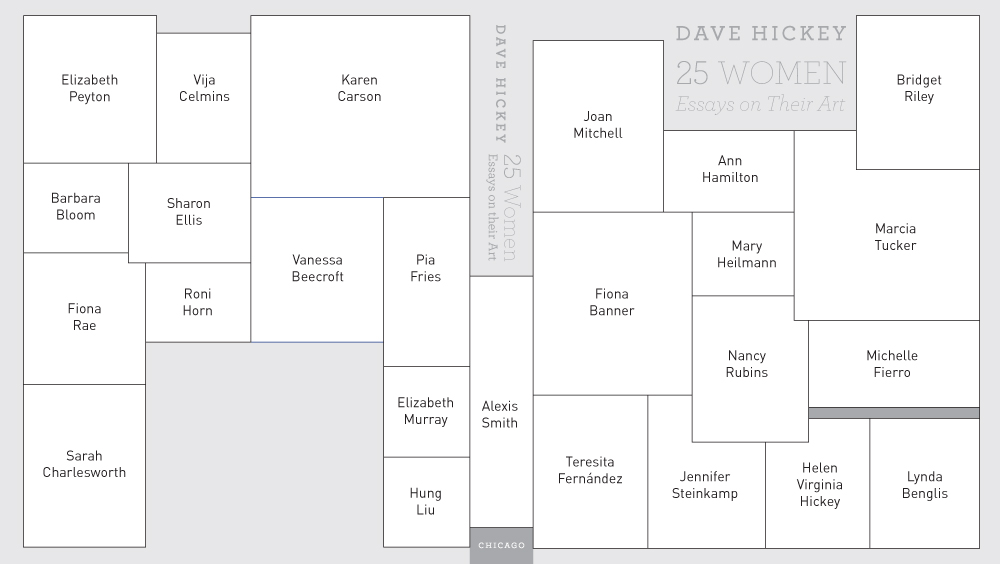

Key to the cover photographs.

And all the free spirits who died too young.

A Ladies Man

I assembled this book of essays on the work of women artists because I wanted to do something to honor my late friend Marcia Tucker, who was my first rabbi in the art world. When Marcia was curator at the Whitney, I cold-called her office to set up a lunch date. She said, How will I recognize you? I told her I would be the black guy in the cowboy hat. She was disappointed when I showed up white and hatless, but she laughed and told me that people are not usually so spunky with museum curators. I acknowledged this as a fault, and over the next few months Marcia recruited me to serve as the Sherpa on her art treks. She called me Cowboy, and I called her the Queen of Poland, out of respect for her status. We began in the late morning, slogging through the snow and slush of the Manhattan winter, past haunted buildings. We climbed stairwells that ascended into the mist. We visited artists studios all day, because this was back when artists had a lot of art in their studios.

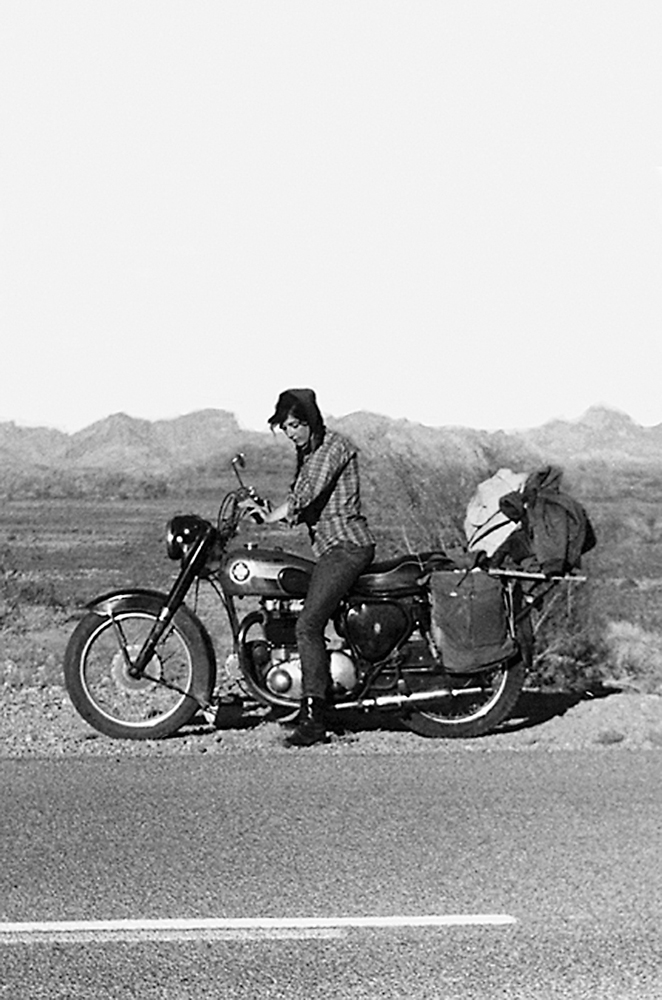

Afterward, we would have cocktails in a dark hotel bar on Madison Avenue where they played Angel Eyes and Lush Life on the sound system. We talked about what we had seen and who we were. I was obviously being mentored, and it was great. It was so New York, so noir, and, actually, so sweet that we almost had to drift away from our pleasant conspiracy to deal with the frazzled business of our lives. In the process, though, I learned everything I needed to know about the art world of the early seventies. I met nearly everyone I needed to meet as a consequence of knowing her. My debt to Marcia is incalculable. She was brave, energetic, and nonjudgmental to the point of having no taste at all. This was OK because I had enough taste for us both. Marcia thought art was about holding back the night. I am from the West. I thought art was about holding back the professors, but no matter. Marcia would go on to invent The New Museum and reinvent herself as a politically correct museum director. I would become a very bad boy for writing an arrogant book about beauty. We ended up on opposite sides of the river, but I always loved her. She was a warrior, a woman of the world, and she liked Harleys. So whats not to love? I miss the Queen of Poland and I miss her being here.

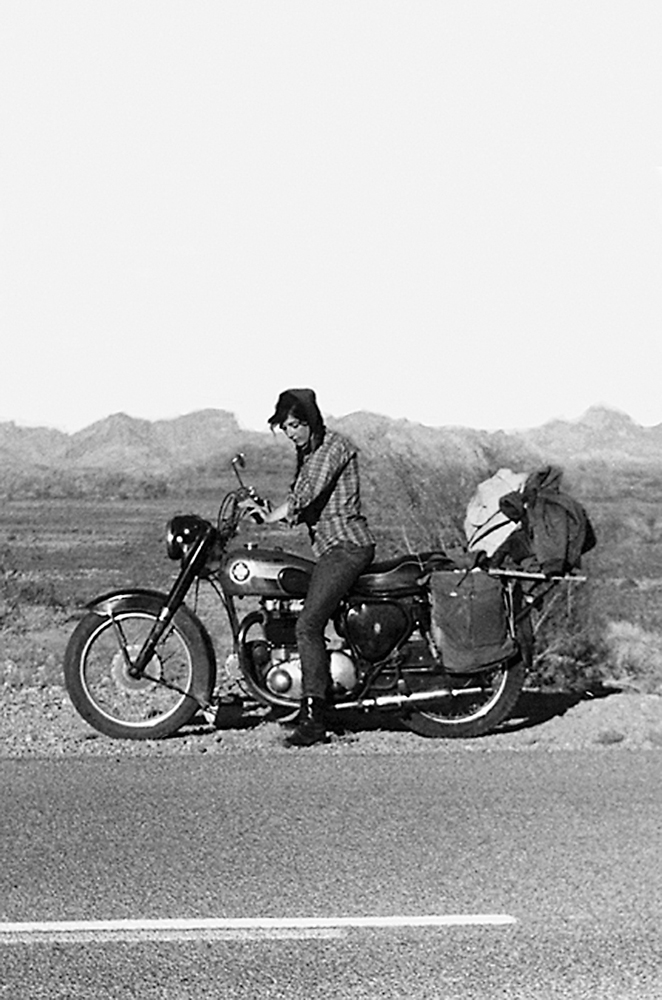

Cover from A Short Life of Trouble: Forty Years in the New York Art World, by Marcia Tucker (University of California Press, 2008). Photo by Michael Tucker.

In her honor, I scrolled my hard drive and came up with thirty essays on the work of women artists. I trimmed the juvenilia and ended up with twenty-five women, counting Marcia and my mom. I checked the Internet for competition, and I was amazed to discover that there is a lot of journalistic writing about women artists, but not much at all by way of critical prose. So heres a little brick for the wall, although this is far from a synoptic book. It is not a fair book either, but to its credit, it does not set out to colonize womens art. The women in this book asked me to write about their work and found me enthusiastic about the prospectmostly because I am an adept of difficulty. I love art that is evanescent and very far away. I love the mystery of gazing across the craquelure of gender gaps that still deploy themselves like canyons across our provisional utopia. American men still treat women with casual cruelty, even the women they love, but there is no agenda here.

There is a lot about art in this book. That is what I do. There is a lot of euphony, death, vogue, fanciful narrative, and fugitive nuance. There is some interesting grammar and more digression than I usually tolerate because a lot of art is best talked about by talking about something else, lest writing shatter the art like a fragile leaf in clumsy hands. What is not here is art politics, which I find abhorrent, and there is not much about feminism. I have never not been a feminist, and it really seems corny to say Dern it! Everybody should be a feminist! Also, I retain a vestigial temerity from the days of identity politics, when men could best demonstrate their feminism by staying away from women so the women could talkby not writing about womens art so women could write about it. This shock and awe feminism without men was not much of a consolation for me. I remember confessing to one adamant Valkyrie that, damn it, I liked women. She replied that if I liked women, my feminism didnt count.

Even so, I have always lived like a slightly bewildered Hagrid in a palace of talented women. I know firsthand how much they pay for their freedom. My grandmother was a businesswoman. My mother was a very successful businesswomen and a professor. My sister is a businesswoman. My wife is a professor, and all my favorite editors are women; all my favorite art dealers are women; and most of my favorite people are women. Meanwhile, the men in my family have always been charismatic wastrelsmyself among themso I have seen the hammer of sexism come down up close, and, if I need to be reminded, I look right over there at this tiny, battered, Montgomery Ward, fake-leather suitcase with my mothers name engraved in gold leaf under the handle. Helen, it says.

My mother bought that little suitcase to venture forth as the first member of her family to go to college since the Civil War. It is the bravest object I own, that dumb little suitcase. When she was promoted to full professor in economics, she gave it to me, not as a gift, but to punish me for wasting my life on rock-and-roll and art, and writing for magazines like