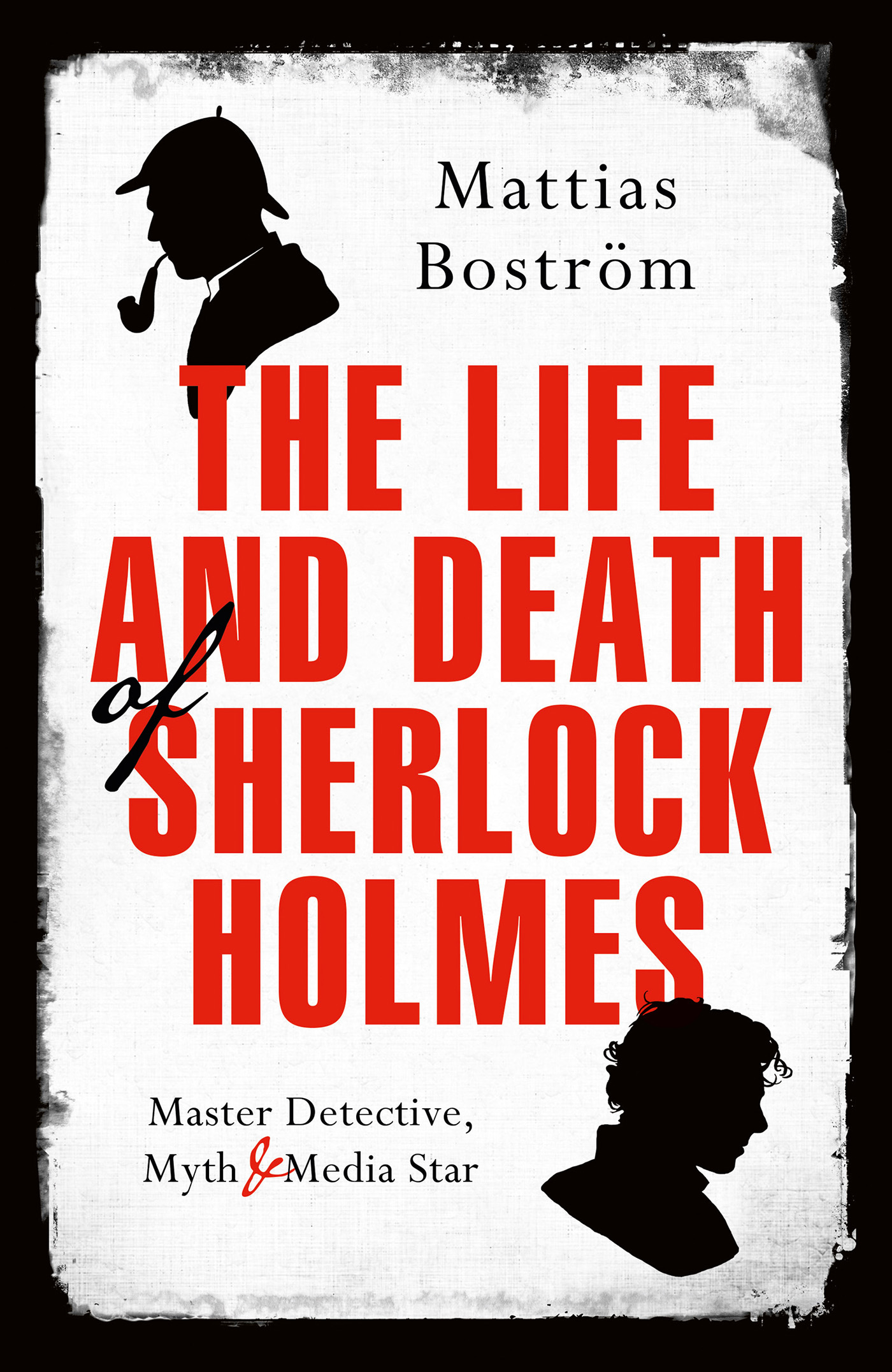

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

Translated from the Swedish by Michael Gallagher

Mattias Bostrm

www.headofzeus.com

Everyone knows Sherlock Holmes. But what made this fictional character into such a lasting success, despite the authors own attempt to escape his invention?

In The Life and Death of Sherlock Holmes , Sherlock Holmes expert Mattias Bostrm recreates the full story behind the legend for the first time. It includes tales of unexpected fortune, accidental romance and inheritances gone awry and tells of the actors, writers, readers and other players who have transformed Sherlock Holmes from the gentleman amateur of the Victorian era to the odd genius of today.

From a young Arthur Conan Doyle sitting in a Scottish lecture hall taking notes on his medical professors powers of observation to the pair of modern-day fans who brainstormed the idea behind the TV sensation Sherlock; from the publishing worlds first literary agent to the Georgian princess who showed up at the Conan Doyle estate and altered a legacy, the book follows the men and women who have created and perpetuated the myth. Told in fast-paced, novelistic prose, The Life and Death of Sherlock Holmes is a singular celebration of the most famous detective in the world.

Contents

I T ALL STARTED on a train.

Thats where the idea came to Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss. They were going to modernize one of the worlds most renowned literary charactersremove the filter of a misty London, full of hansom cabsand bring Sherlock Holmes up to date, placing him squarely in our high-tech, contemporary world. Sir Arthur Conan Doyles creation would go from Victorian gentleman detective to modern, eccentric geniusfrom Holmes to Sherlock.

This, of course, was sacrilege. Such a television show was bound to be controversial among the fans, as Moffat and Gatiss were aware. Nevertheless, the more they discussed it, the stronger the idea seemed to grow. They wanted to do away with the classic symbolsthe deerstalker, the pipe, the magnifying glassall the nostalgia that was getting in the way, all those things that made Holmes seem more like a well-defined silhouette than a complex human being. The changes would, however, need to be made with great love for the original stories. The pair wanted to bring viewers really close to the original friendship between Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, closer than anyone had brought them since the figures were born in the authors imagination well over a century before.

This was just a few years after the turn of the millennium, and for the time being their plan was no more than a tiny seedjust a topic of conversation during Gatiss and Moffats commute from London to their script-writing jobs at BBC Wales in Cardiff.

But there were lots of train journeys. And the idea kept on growing.

*

A short time later, on January 7, 2006, Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat found themselves at the Sherlock Holmes Society of Londons annual dinner. Gatiss had been invited to speak, and Moffat was there as his guest.

Gatiss had also attended the previous year. He had been invited by a friend, Stephen Fry, a member of the society already in his early teens, who had been guest of honor and after-dinner speaker on that occasion. Gatiss had asked the societys chairman for an invitation for the 2006 dinner.

So there he was, in his tuxedo and black bow tie, about to make a speech in front of the assembled membersHolmesians, as they called themselves, or Sherlockians, for those who preferred the more widespread American term.

They were seated in a dining room in the House of Commons, a magnificent and thoroughly fitting venue for a Victorian flight of fancy, with its carved oak panels and beautiful evening views across the Thames to the lights of Lambeth on the opposite bank. Slightly to the left was the London Eye, the symbol of modern London and thus of an updated version of Sherlock Holmes, too.

It was an anxious moment. That evening Gatiss and Moffat would float their idea before a broad audience for the first timeand these particular guinea pigs were among the most critical, circumspect subjects you could imagine.

Mark Gatiss was coming to the end of his speech. He had told the members of his long-standing interest in Holmes and had arrived at the train conversation with Moffat.

We began to discuss the question: could Holmes be brought alive for a whole new generation? Gatiss said. He described the scenario: A young army doctor, wounded in Afghanistan, finds himself alone and friendless in London. That detail about Afghanistan had been crucial for Gatiss and Moffat. The tale of Sherlock Holmes could in fact be introduced in the same way, regardless of whether it was set around 1880 or in the present. Those regions that were ravaged by war in the late nineteenth century remain conflict zones to this day.

Short of cash, Gatiss went on, he bumps into an old medical acquaintance, who tells him he knows of someone looking for a flatmate. This blokes all right but a little odd. And so Dr. John Watsonwounded in the taking of Kabul from the Talibanmeets Sherlock Holmes, a geeky, nervous young man rather too fond of drugs, whos amassed a lot of out-of-the-way knowledge on his laptop. Gatiss looked out over the assembled Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts. Its only a thought. A beginning.

The Sherlockians were a hardened bunch. Many attempts at recasting Sherlock Holmes had been made through the years. Some had succeeded, others had not. Would Gatiss and Moffats idea of bringing Holmes into the present find fertile ground?

But to prove Holmes immortal, Gatiss continued, its essential hes not preserved in Victorian aspicbut allowed to live again!

The general opinion among those present seemed to be that this was, well, controversial. It was also, nonetheless, intelligent, funny, and stimulatingmuch like Gatiss himself.

The mood in the dining room was cheerful. Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat no longer had to hold their breath. Stage one was complete.

Every era had its own Sherlock Holmes. For over a century the famous detective had been reimagined to fit contemporary trends and ideals. Perhaps Gatiss and Moffat, with their new approach, would be the ones to ensure that yet another generation discovered Sherlock Holmes.

Ladies and gentlemen, Gatiss concluded, I give you Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes, and Dr. Watson. Forever.

18781887

I T WAS A Friday in late autumn 1878. Edinburghs Royal Infirmary had moved to new premises at Lauriston Place, surroundings that benefited from significantly cleaner air than the old location toward the center of town. Although the slum clearances around High Street and the steep alleys of the Old Town had been under way for almost a century, mortality was still much higher there than in the more prosperous New Town neighborhood.

With its new Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh was now home to the largest and best-planned hospital in Britain, containing as many as six hundred beds. It was also a place where a new generation of doctors undertook studies in modern, clinically based medicine.

A man hurried down one of the hospitals corridors, waving a towel enthusiastically. This was a familiar sight to his colleagues and to his students, who always arrived on time for his lectures. He held his head high; his steel-gray hair stood on end; his gait was jerky and energetic; his arms were like two great pendulums.