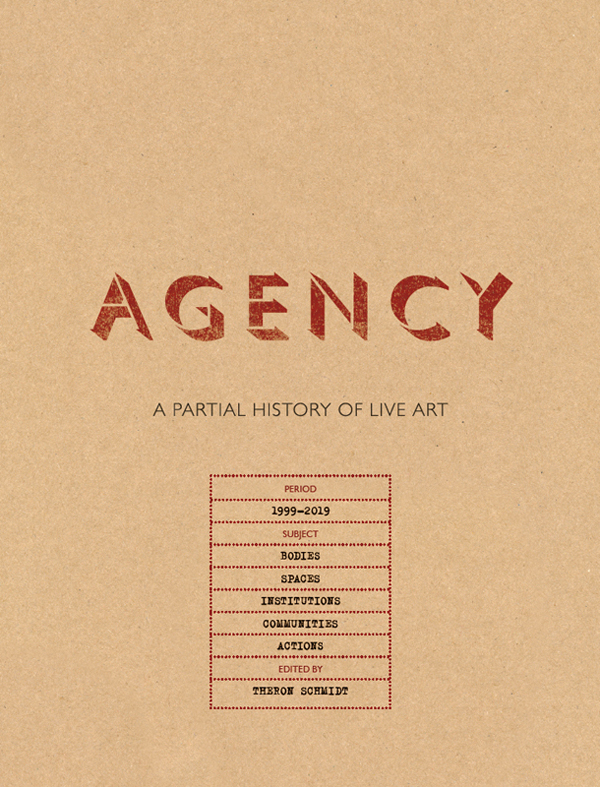

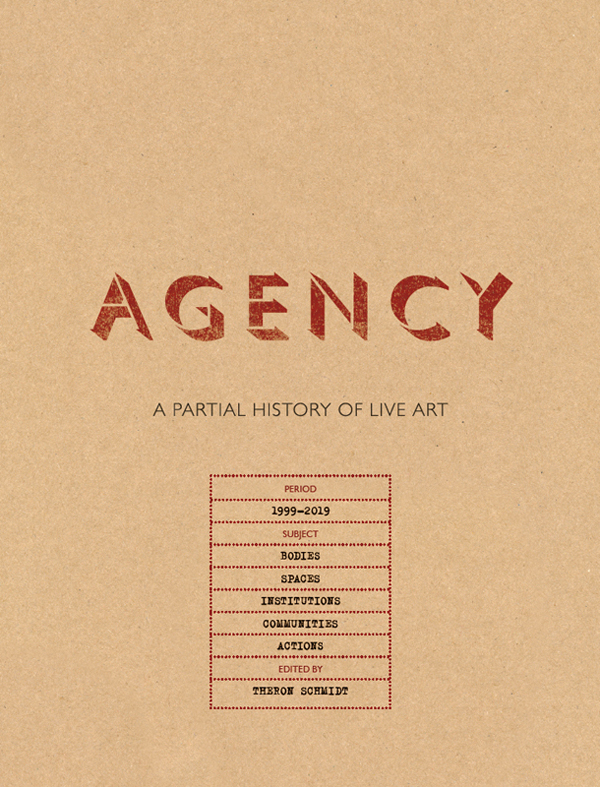

Contents

Figures

Bobby Baker, Pull Yourself Together, part of Small Acts at the Millennium and Mental Health Action Week (2000). Image Hugo Glendinning.

When Catherine Ugwu and I launched the Live Art Development Agency in January 1999 we had no idea it would still be going twenty years later. In truth I didnt imagine it would last beyond the term of our first Arts Council grant, let alone that LADA would grow from a two-man band based around a couple of desks, shelves and blank pieces of paper, to a six-person operation running a complex web of projects, resources, opportunities, and publishing.

The unexpected longevity and unimagined expansion of LADA in many ways speaks to advances in the profile, position, and possibilities of Live Art over the last twenty years. Some of those advances are reflected in this partial collection of provocations and conversations curated by Theron Schmidt, which considers the agency of Live Art in relation to the big questions of Bodies, Spaces, Institutions, Communities, and Actions, and does so through the lens of LADA.

Published on the occasion of LADAs 20th anniversary in 2019, AGENCY is, for me at least, an opportunity to reflect on how the shifts and developments within Live Art have impacted on LADAs work, and in turn, on the ways in which what LADA does, and how it does it, have adapted and evolved.

Perhaps the biggest shift that has affected almost everyone involved with Live Art is technology. Developments in technologies allow us all to create and access online platforms to research, connect, share, catalogue, publish, and disseminate Live Art in unprecedented ways. Technology is a critical factor in the heightened level of interest and developments in the histories and archiving of Live Art and has enabled artists, scholars, and curators to both research, and create new contexts for, underrepresented artists and untold histories. Technology has been instrumental in shifts in the critical thinking and popular profile of Live Art, making it possible for artists, writers, and audiences to bypass the mainstream gatekeepers of culture. Its impossible to overestimate the impact of technology on the functionality of LADAour capacity to document, archive, publish, and disperse Live Art through digital publications and online platforms such as Live Online and, through them, to reach and connect artists and thinkers across the globe and to go where Live Art hasnt gone before.

The institutional embrace of Live Art over the last twenty years is another hugely significant shift. When LADA started in 1999, Live Art was still very much the runt of the litter in the cultural life of the UK, ignored, trashed, or undervalued by most institutions. But the last twenty years has seen an unparalleled institutional engagement with experiential, experimental, and ephemeral practices, with many previously impenetrable museums, galleries, theatres, and festivals opening their doors to Live Art. Since LADAs Live Culture programme at Tate Modern in 2003, the 2012 opening of Tate Tanks (the worlds first museum space dedicated to performance), and the extraordinary range of partnerships built by Live Art programmers and festivals across the UK, its now tempting to count the institutions that havent in some way embraced Live Arts ways of working rather than those that have.

The widespread teaching and study of Live Art within Higher Education is an equally catalytic development that has impacted on the increasing pervasiveness of Live Art and influenced the work of LADA. In 1999, only a handful of universities and art colleges had a commitment to such kinds of process-based artistic experimentation, or understandings of how it could contribute to scholarly research and discourse. The students who made it to LADAs office to see what was on our shelvesmost of them rejects or refugees from more traditional disciplineshad invariably found us themselves, and not many artists we knew were employed to teach. LADA started at the same time as the artist Lois Weaver joined the Drama Department at Queen Mary University of London and one of our first collaborations was to set up an informal Live Art in Higher Education in London Forum. Every six months or so for a couple of years, a motley crew of academics would gather together to discuss the challenges of bringing the practices and approaches they were so passionate about into the academy. Today couldnt be more differentLADAs Study Room regularly welcomes students sent to us by their tutors, hosts scores of student groups from universities across the UK and beyond, many artists now hold teaching positions (albeit some more precariously than others), all kinds of Live Art related PhDs are being undertaken, and LADA works closely with a wide range of scholars and universities. Performance Studies international:12, Performing Rights, hosted by Queen Mary in 2006, with LADA as its cultural partner, was a pivotal moment for us in testing ways we could position artistic practices within research focused contexts, and vice versa. Performance Matters (2009-2013)an Arts and Humanities Research Council funded research project in collaboration with Adrian Heathfield of University of Roehampton and Gavin Butt of Goldsmiths, University of London, considering the cultural value of Live Arthad a seismic impact on Live Arts, and indeed LADAs, role within research culture. And in 2018, LADA partnered with Queen Mary University of London on a new MA Live Art. From where I sit, Live Art in Higher Education has come a long way since 1999.

This institutional embrace and academic legitimacy should not in any way suggest that Live Art has somehow been tamed. Far from it. Live Art is still a fiercely politicised, provocative, and unruly area of practice. Live Art is all about differencedifferent ways of making and experiencing art; different ways of documenting and dispersing performance; different ways of being in, and seeing, the world; and different ways of occupying the institution and rethinking approaches to research and knowledge.

In 1999, the kinds of artists and practices LADA particularly championed were not only interested in the body as their site and subject, and in testing the nature, role, and experience of art, but were just as concerned with representations of cultural difference, with the construction and performance of identity, with giving visibility to the hidden and forbidden. For LADA, Live Art was more than a space to think about what art is and can do, it was a space to think about who has agency and what they can do with it.

Over the last twenty years, the embodied and subversive practices around the politics of the body that so characterised much Live Art in the late 1990s are still as vital and urgent as everbut Live Art as a practice and an approach has also influenced a wider spectrum of process-based, experiential art, spanning all kinds of disciplines and subjectivities, and testing new forms of audience relationships. Since 2016, LADA has been working with the artist and researcher Sibylle Peters and Tate Early Years and Families Programme on projects inviting children and adults to look at the world together through Live Art. With these partners we have produced PLAYING UP, an intergenerational game based on historical Live Art works, and