Reflections of a Scientist

Henry Eyring

1983 Deseret Book CompanyAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, Deseret Book Company, P.O. Box 30178, Salt Lake City, Utah 84130. This work is not an official publication of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of the Church or of Deseret Book Company.Deseret Book is a registered trademark of Deseret Book Company.

TRUTH

All day long, on a fiercely hot Friday in September 1919, I hauled hay in Pima, Arizona. On Monday I was going to start classes at the University of Arizona, where I was to study mining engineering. In the evening my father, as fathers often do, felt that he'd like to have a last talk with his son. He wanted to be sure I'd stay on the straight and narrow. He said, "Henry, won't you come and sit down. I want to talk to you."

Well, I'd rather do that than pitch hay any time. So, I went over and sat down with him.

"We're pretty good friends, aren't we?"

"Yes," I said, "I think we are."

"Henry, we've ridden together on the range, and we've farmed together. I think we understand each other. Well, I want to say this to you: I'm convinced that the Lord used the Prophet Joseph Smith to restore His Church. For me, that is a reality. I haven't any doubt about it. Now, there are a lot of other matters that are much less clear to me. But in this Church you don't have to believe anything that isn't true. You go over to the University of Arizona and learn everything you can, and whatever is true is a part of the gospel. The Lord is actually running this universe. And I want to tell you something else: if you go to the University and are not profane, if you'll live in such a way that you'll feel comfortable in the company of good people, and if you go to church and do the other things that we've always done, I won't worry about your getting away from the Lord."

That's about the best advice I ever got. It has simplified my life. All I have to do is live in a wholesome way, which is best for me anyway, and be busy about finding truth wherever I can. I suspect that you would enjoy that formula too.

The significant thing about a scientist is this: he simply expects the truth to prevail because it is the truth. He doesn't work very much on the reactions of the heart. In science, the thing is, and its being so is something one cannot resent. If a thing is wrong, nothing can save it, and if it is right, it cannot help succeeding.

So it is with the gospel. I once had the privilege of attending a youth conference and responding to questions of the assembled young people. A young man asked, "In high school we are taught such things as pre-Adamic men, but we hear another thing in Church. What should I do about it?"

I think I gave the right answer. I said, "In this Church, you only have to believe the truth. Find out what the truth is!"

This Church is not worried about that question or other similar questions, because the Church is committed only to the truth. I do not mean to say that individuals in the Church always know the whole truth, but we have the humility sometimes to say we do not know all the answers about these things.

Some have asked me, "Is there any conflict between science and religion?" There is no conflict in the mind of God, but often there is conflict in the minds of men. Through the eternities, we are going to get closer and closer to understanding the mind of God; then the conflicts will disappear.

I'm happy to represent a people who, throughout their history, have encouraged learning and scholarship in all fields of honorable endeavor, a people who have among their scriptural teachings such lofty concepts as these: "The glory of God is intelligence, or, in other words, light and truth." (.)

To us has come the following, which we regard as a divine injunction: "Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you, that you may be instructed more perfectly in theory, in principle, in doctrine, in the law of the gospel, in all things that pertain unto the kingdom of God, that are expedient for you to understand; of things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass; things which are at home, things which are abroad; the wars and the perplexities of the nations, and the judgments which are on the land; and a knowledge also of countries and of kingdoms." (.)

Here is the spirit of true religion, an honest seeking after knowledge of all things of heaven and earth.

HEREDITY AND ENVIRONMENT

Once, after World War II, I was teasing a Belgian a little bit. He said, "There has never been a good German, ever!" I said, "There must have been one by mistake sometime." He then asked me what nationalities I came from, and I replied, "I'm half German and half English." He said, "The worst two nations on earth!" Apparently, considering my hereditary background, you may want to take serious thought before continuing with this book.

It takes several ingredients to make a good scientist. One is being bright, in seeing and grasping ideas quickly. Another is a sense of self-worth that allows you to keep struggling along even when you might seem lost in the woods for the moment. It seems to me that both heredity and environment play a role in these attributes. Undoubtedly, the prospective scientist should arrange to be born with the right genes. Anyone who has examined the differences between individuals with presumably equal training cannot escape this conclusion. However, even a gifted person requires a stimulating environment.

Ideally, a stimulating environment also provides a sense of safety and well-being. It might even make you feel a little better about yourself than a completely unbiased evaluation would seem to warrant. Lowell Bennion, speaking from his wide experience in teaching in the LDS Institute at the University of Utah, said it this way: "At first I thought the big problem of university students would be questions in logic and philosophy, but I soon found out that when they were happy and socially accepted, their imagined difficulties melted away."

To illustrate this with my own life, let me tell you about a happy childhood that may seem long ago and far away to you, but seems yesterday and close to me.

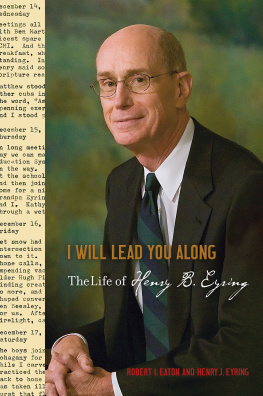

I was born in 1901 and grew up on ranches and farms in Mexico and Arizona in a devoutly Mormon family. I don't remember my grandfather Henry Eyring, since he died the year after I was born. I grew up with the image (from what my parents had told me) of him giving me a name and a blessing when I was a baby. They said he was so pleased with his namesake that he cried. Likewise, I am delighted to bear his name.

Grandfather, who spoke seven languages and was well educated in his native Germany, came to America as an eighteen-year-old with his sister, after his father had lost the family fortune in a business venture. Grandfather said later that the loss was actually a blessing because he was more susceptible to the teachings of the Church as a clerk in a wholesale drug firm in St. Louis than he would have been as a prosperous apothecary in Germany.

In later life he ran a cooperative store in Colonia Juarez, one of the Mormon colonies in Mexico. It was said that he could have run it as his own business, for his own profit, but chose to continue as a cooperative because that benefited others. Porfirio Diaz, president of the Mexican republic for thirty years, stated in a letter that Henry Eyring was one of the most strictly honest men he had ever met. Such a grandfather, especially one with the same name, was and is a great comfort and strength to me.