Copyright 2012, 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Originally published in hardcover in 2012 by Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

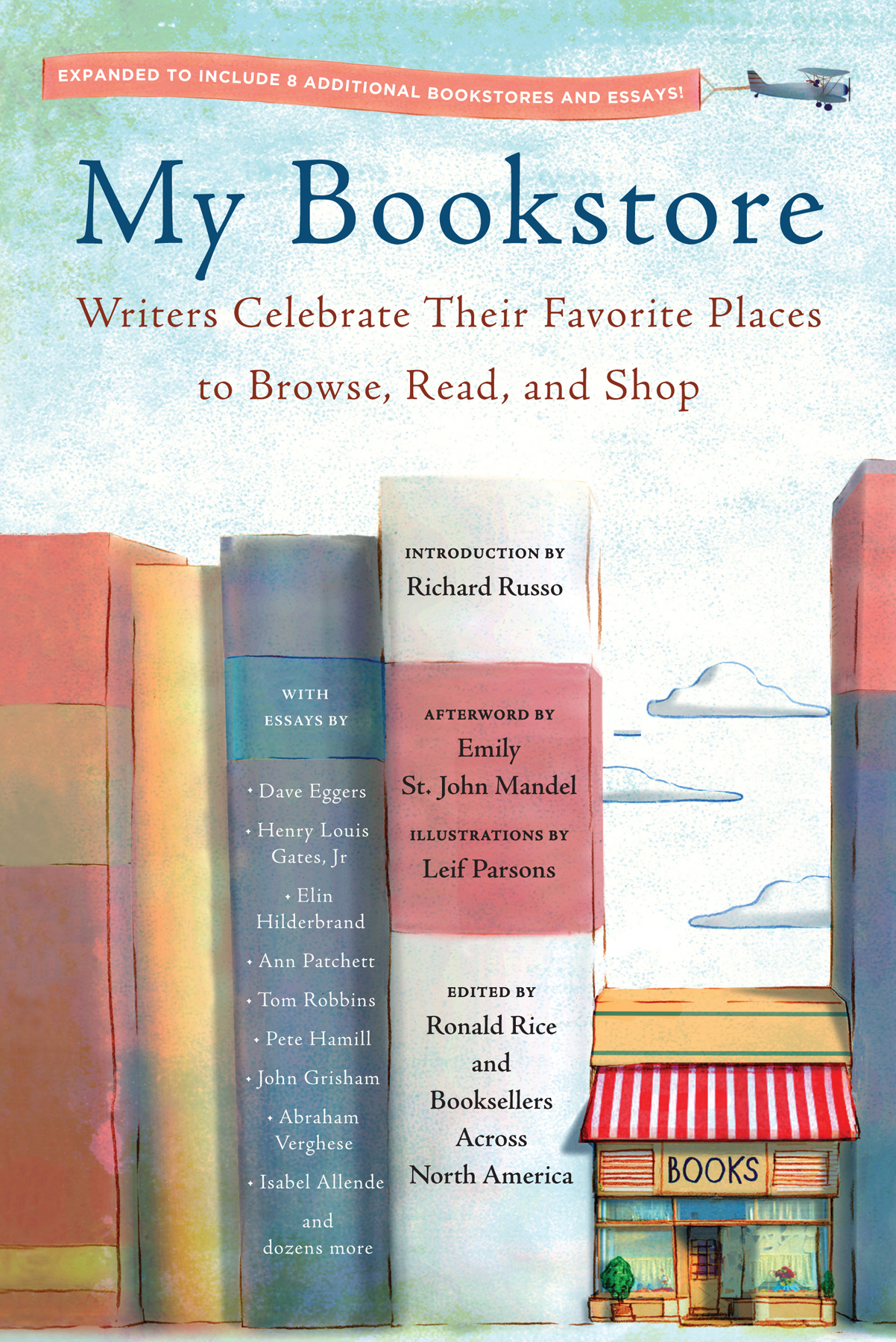

The first great bookstore in my life wasnt really even a bookstore. Alvord and Smith was located on North Main Street in Gloversville, New York, and if memory serves, they referred to themselves as stationers. I dont remember the place being air-conditioned, but it was always dark and cool inside, even on the most sweltering summer days. In addition to a very small selection of books, the store sold boxed stationery, diaries, journals, and high-end fountain and ballpoint-pen sets, as well as drafting and art supplies: brushes, rulers, compasses, slide rules, sketch pads, canvas, and tubes of paint. The shelves went up and up the walls, all the way to the high ceiling, and I remember wondering what was in the cardboard boxes so far beyond my reach. The same things that were on the shelves below? Other, undreamed-of wonders? Alvord and Smith was a store for people whothough I couldnt have articulated it at the timehad aspirations beyond life in a grungy mill town. It was never busy.

Because she worked all week, my mother and I ran our weekly errands on Saturday mornings, and Alvord and Smith was usually our first stop. There, Id plop down on the floor in front of the bottom two shelves where the childrens books were displayed: long, uniform phalanxes of the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew mysteries as well as the lesser-known but, to my mind, far superior Ken Holt and Rick Brandt series. I can still remember the incomparable thrill of coming upon that elusive number eleven or seventeen in my favorite series, the one Id been searching for for years, now magically there, where it hadnt been the week before, filling me with wonder at the way the world worked, how you had to wait to the point of almost unbearable longing for the good stuff in life. (It would take five decades and the emergence of Amazon.com, with its point-and-click, to vanquish that primal wonder.) Just as mysterious as the appearance of the books themselves was where the money to pay for them came from. My mother was forever reminding me that money didnt grow on trees, at least not on ours, and if I had my eye on some toy gun at Woolworth, shed say that this was what my allowance, which I saved dutifully, was for. Otherwise, Id have to wait for my birthday or Christmas. But if I was a dollar short for a book, shed always find one in her purse (how? where?) so I wouldnt have to wait the extra week, during which time some other boy might buy it.

Coming out of Alvord and Smith, blinking in the bright sunlight, you could see all the way down Main Street, past the Four Corners, to South Main, where the gin mills and pool hall were. Outside these stood dusky, shiftless, idle men, flexing at the knees and whistling at the pretty women who passed by. Occasionally my father was among them. Much later, when I turned 18, legal drinking age in New York back then, I would join him in those same dives. Like the stationery store, they were cool and dark and mysterious, and for a while I preferred them, though I never really belonged. Thats what Id felt as a boy, sitting on the floor at Alvord and Smith, touching, lovingly, the spines of books: Here was a place I belonged.

Fast-forward twenty years. Im now an assistant professor of English, married, with two small daughters, living in New Haven, Connecticut, teaching full-time and trying desperately to become a writer. My wife and I are nearly as poor as my mother and I had been back in Gloversville. We live in an apartment in a neighborhood where experience has taught me to put a sign in both the front and rear windows of our old beater, telling the neighborhood thieves the car is unlocked so they wont smash the windows. There is nothing of value inside, I write, the radio and speakers having been boosted long ago. But of course, thats a lie. A university professor, I forget books in the car all the time. Sometimes when I come out in the morning, its clear that someones been in the car, but the books are right where I left them. No takers.

Once a month or so, on a Saturday night, if weve managed to save up, my wife and I go down to Wooster Street and have an inexpensivethough expensive to usmeal in an Italian restaurant. On the way home we always stop at Atticus Bookstore, where, miraculously, the early-morning edition of the Sunday Times awaits us. How can this be? Tomorrows newspaper, today. Atticus is a clean, well-lighted place, one of the first bookstores in the country to understand that books and good coffee go together. Its stretching our budget after splurging on a restaurant meal, but we buy coffees and find a tiny bistro table and take books down off nearby shelves to examine. Books. By this time Ive published a few short stories, but nothing so grand as a book. From where we sit I can see the Rs, the exact spot where my book will sit if I ever publish one. I may, one day, rub spines with Philip Roth. In a way, its almost too much to contemplate. In another, well, I cant help feeling I belong here, just as I did on the floor of Alvords in Gloversville.

Many people love good bookstores, but writers? We completely lose our heads over them. We tell each other stories about them. We form lifelong, irrational attachments to our favorites. We take every independent bookstores failure personally. Surely theres something we might have done. We do not hate e-books purchased onlinewell, OK, some of us dobut we owe our careers, at least my generation of writers does, to the great independents, so many of them long gone now. Those that remain gamely continue to fight the good fight, even as customers increasingly use their stores as showrooms, their employees for their expertise, and their sales-tax dollars to fund their schools, but then go home and surrender to the online retailers chilly embrace. They point and click, and in this simple act, without meaning to, undermine the future of the next generation of writers and the one after that. Because its independent booksellers who always get the word out (as they did for me). With their help, if theyre still around, great young writers you dont know about yet will take their place on shelves next to their heroes, from Margaret Atwood to Emile Zola, just as I have somehow managed to do. Without them, well, I shudder to think.