I wish to acknowledge the untiring assistance offered to me by Andrew Croziers wife Jean, and by his brother, Philip; without their generous cooperation it would have been impossible to put this volume together. In addition, the assistance given by Derek Slade in putting together the bibliography has been invaluable. I also wish to dedicate this book to my wife, Kay, whose patience while I have been closeted in my study has been a hallmark of her support for the whole venture. Ian Brinton

Soon after Andrew Croziers death in April 2008 the

Independent published an obituary by Nicholas Johnson, himself a prominent poet and founder of Etruscan Books. Subtitled Poet and poets champion, Johnsons piece pointed to the extraordinary way in which Crozier had fostered the world of poetry in England from the mid-1960s to his premature death soon after his retirement from the University of Sussex: At just 20 years old, the poet Andrew Crozier began to nurture and revitalise through his small-press publishing a rich terrain of first American, then British, modernist poetry. This had a rapid effect for his peers, principally those associated with the Cambridge School.

Crozier disseminated, circulated and, with what became an increasingly anonymous generosity, encouraged and stimulated countless writers and visual artists. If he partly achieved this as an editor, archivist, publisher and teacher, it was quietly reflective of his precise gift as a poet. Now his poetry is out of print. In the two years before his death this last point was a matter of some serious debate, and there was some important correspondence between Andrew Crozier and Michael Schmidt about the possibility of producing a Selected Writings which might include both poetry and some prose. In his response to one of Schmidts letters, Crozier, who had only recently retired from academic life, provides some interesting insights into what he was working on right up until the end: 2nd May 2006 Retirement itself will, surely, have consequences for writing of any sort, although I have no strong sense of what is likely. This is relevant to my perplexity about how to respond to your invitation.

Hitherto I have responded to expressions of interest in publishing a new collected edition of my poems by saying that to do so seemed premature while I had rather little to add to All Where Each Is, and difficult to justify. (Indeed, difficult to justify to myself although that book has been out of print for some while.) What Ive separately thought is that the situation requires the publication of a further separate collection, including Free Running Bitch (previously published in Conductors of Chaos), before anything else. Ive made these points to other publishers more tersely than I do here, hence my responses have, reasonably enough, as well as correctly, been taken as refusals. I dont think, however, that this response is either appropriate or sufficient when the expression of interest comes from you and Carcanet. Hence my perplexity about how to respond; you will appreciate, I do hope, that the perplexity is with reference to my situation. Since your invitation is couched in terms of writings perhaps I should say something about critical writings, not the least because some pieces of critical writing are foremost in my mind at present.

I have in hand essays on John James (for a collection on him) and on Basil Kings Mirage. Looming over both these, and most of all else, is a long essay on Harry Roskolenko, a minor but symptomatic poet of the 1930s and 1940s. (He began as one of Zukofskys Objectivists, and by the end of the 1930s was the American arm of the New Apocalypse. Add to this that he was part of the Left Opposition i.e. Trotskyish working undercover in the CPUSA and, from my point of view, he has everything going for him.) I give this detail in order to point out that my critical writing is miscellaneous, as it stands, but also, notionally at least, some of it preliminary to separately developed monographs on the Objectivists and the New Apocalypse. A few days later I received a letter from Andrew which again discussed the possibility of his work being put back into the public eye: 11th May Your point that my work is unobtainable is not lost on me, indeed it is one I cant avoid as an emphatic consideration whenever (unfrequently) I contemplate my position qua poet.

It doesnt outweigh, in the balance of wishes and intentions, my hesitancies about republication tout court. I dont want to appear, not the least to myself, as resting on my laurels. Were I to abjure poetry, or were I dead, the work could be left to make its own way as helped by others. The second of these circumstances is not an otiose form of words: publication can seem like a symbolic death, a book like a monument, with damaging as well as painful effects. There is another side to this, of course, connected with the vanity of not wishing to appear an historical figure. Enough said the better! In an article for the London Review of Books in July 1997, Jeremy Harding highlighted some of the essential ingredients of a Crozier poem and made it abundantly clear why this poetry most certainly should be back in print: In his easy vernacular, Crozier tamps down language with the skill of a painter achieving a rare equivalence of terms on the canvas.

Often, too, we find an observed action or a local detail quickly entailed to something larger and simpler: the pattern of day and night, seasonal change, or the slippage of light and shadow. This has the effect of ascribing thought and emotion not to the speaking subject (the poet) but to the processes of the poem. A deceptively shambling manner, with its cats cradles of clauses, promiscuous participles and other equivocations of grammar spreads the load of the bigger themes and adds to a sense of forms thinking aloud, in a number of voices. Once again, the approach is painterly: the figurative elements of a typical Crozier poem are briefly acknowledged and then abstracted by the momentum of its composition into the broadest space it can construe. The result is extraordinary. This collage-like inventiveness was noted in Peter Rileys Guardian obituary from July 2008, as was Croziers proposition that a poem should be constantly and freshly conceived as a construct of language which achieves beauty through a fidelity to the actual.

His meditations on landscape and on the intimacy of the domestic world are expressed in a bared honesty which is the result of considerable discipline. Riley went on to present a vivid picture of that historical figure Andrew Crozier had wryly abjured: From the outset, Crozier worked to bring practitioners together. In 1966 he founded The English Intelligencer, a worksheet circulated among some 30 poets to exchange knowledge of their current activities without worrying too much about finished poems, and from 1964 onwards ran The Ferry Press, which published first or early books of many important British poets in carefully designed editions, frequently with covers designed by then little-known artists, including Patrick Caulfield and Michael Craig-Martin. He collaborated further, in special illustrated editions of his own poetry, with artists such as Ian Tyson, Tom Phillips, and his own brother, Philip Crozier. His criticism was important, but remains as yet scattered in periodicals and anthologies, and some of his projects were never completed. The stress was again on sweeping the board clean and examining the history afresh: what took place, what was produced and what its value might be, and this naturally resulted in reversals of received positions, and the rescuing of forgotten poets, which became almost a speciality of his.

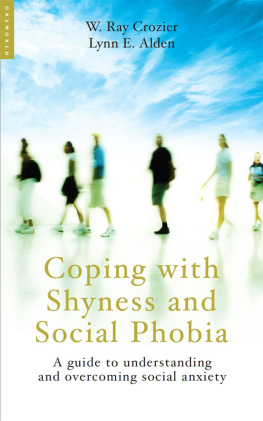

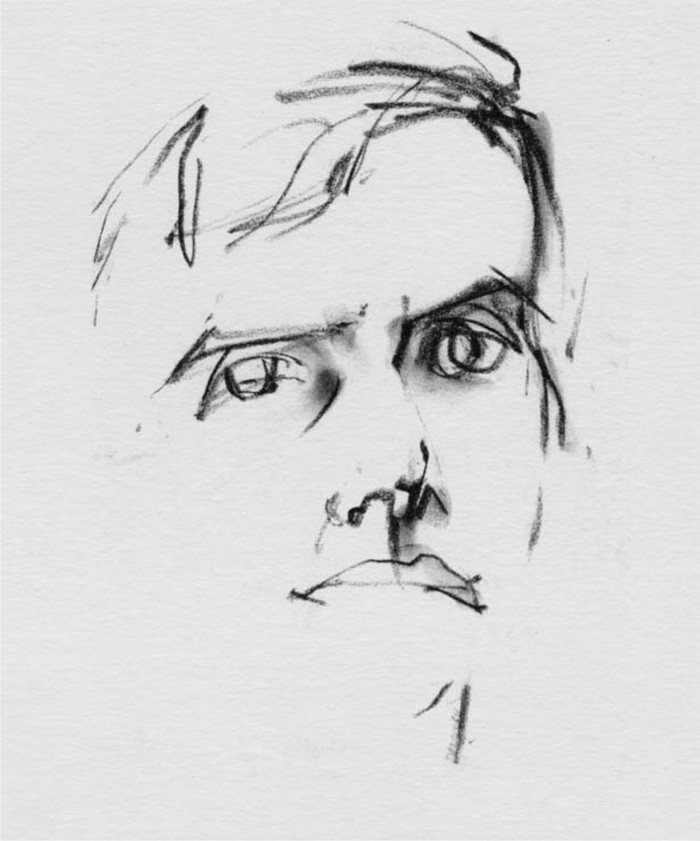

Drawing of Andrew Crozier by Fielding Dawson, New York 1965 Reproduced by permission

Drawing of Andrew Crozier by Fielding Dawson, New York 1965 Reproduced by permission