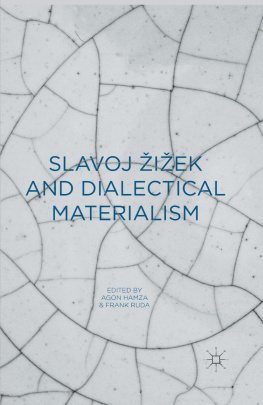

Dialectical Passions

COLUMBIA THEMES IN PHILOSOPHY,

SOCIAL CRITICISM, AND THE ARTS

COLUMBIA THEMES IN PHILOSOPHY, SOCIAL CRITICISM, AND THE ARTS

Lydia Goehr and Gregg M. Horowitz, Editors

ADVISORY BOARD

J. M. Bernstein

T. J. Clark

Nol Carroll

Arthur C. Danto

Martin Donougho

David Frisby

Boris Gasparov

Eileen Gillooly

Thomas S. Grey

Miriam Bratu Hansen

Robert Hullot-Kentor

Michael Kelly

Richard Leppert

Janet Wolff

Columbia Themes in Philosophy, Social Criticism, and the Arts presents monographs, essay collections, and short books on philosophy and aesthetic theory. It aims to publish books that show the ability of the arts to stimulate critical reflection on modern and contemporary social, political, and cultural life. Art is not now, if it ever was, a realm of human activity independent of the complex realities of social organization and change, political authority and antagonism, cultural domination and resistance. The possibilities of critical thought embedded in the arts are most fruitfully expressed when addressed to readers across the various fields of social and humanistic inquiry. The idea of philosophy in the series title ought to be understood, therefore, to embrace forms of discussion that begin where mere academic expertise exhausts itself, where the rules of social, political, and cultural practice are both affirmed and challenged, and where new thinking takes place. The series does not privilege any particular art, nor does it ask for the arts to be mutually isolated. The series encourages writing from the many fields of thoughtful and critical inquiry.

Lydia Goehr and Daniel Herwitz, eds., The Don Giovanni Moment: Essays on the Legacy of an Opera

Robert Hullot-Kentor, Things Beyond Resemblance: Collected Essays on Theodor W. Adorno

Gianni Vattimo, Arts Claim to Truth, edited by Santiago Zabala, translated by Luca DIsanto

John T. Hamilton, Music, Madness, and the Unworking of Language

Stefan Jonsson, A Brief History of the Masses: Three Revolutions

Richard Eldridge, Life, Literature, and Modernity

Janet Wolff, The Aesthetics of Uncertainty

Lydia Goehr, Elective Affinities: Musical Essays on the History of Aesthetic Theory

Christoph Menke, Tragic Play: Irony and Theater from Sophocles to Beckett, translated by James Phillips

Gyrgy Lukcs, Soul and Form, translated by Anna Bostock and edited by John T. Sanders and Katie Terezakis with an introduction by Judith Butler

Joseph Margolis, The Cultural Space of the Arts and the Infelicities of Reductionism

Herbert Molderings, Art as Experiment: Duchamp and the Aesthetics of Chance, Creativity, and Convention

Whitney Davis, Queer Beauty: Sexuality and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Freud and Beyond

Dialectical Passions

Negation in Postwar Art Theory Gail Day

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York. Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2011 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52062-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Day, Gail.

Dialectical passions : negation in postwar art theory / Gail Day.

p. cm.(Columbia themes in philosophy, social criticism, and the arts)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-14938-9 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-52062-1 (electronic)

1. Art, Modern20th centuryPhilosophy. 2. Art, Modern21st centuryPhilosophy. 3. Negation (Logic) I. Title. II. Series.

N6490.D34 2011

701.18dc22

2010004988

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

Or, the Dizziness of a

Perpetually Self-Engendered Disorder

My most important debt is to Steve Edwards for his unflagging patience, commitment, and engagement. I doubt Dialectical Passions would have been completed without his personal support and his astute readings of its countless drafts. I have also been especially fortunate to have received the inspiration, guidance, and friendship of Fred Orton and wish to take this opportunity to say how thankful I am. Caroline Arscott, John X. Berger, Andrew Hemingway, Alex Potts, Susan Siegfried, and Julia Welbourne have been sustaining presences through the gestation of this book, providing critical insights into my ideas and offering crucial encouragement to persist when stasis prevailed. To the readers of the manuscript, in part or in whole, and at various stages of its development, I owe particular thanks: Caroline (again), Martin Gaughan, Ken Hay, Stewart Martin, Adrian Rifkin, John Roberts, and Fred Schwartz. Their advice and incisive comments have helped clarify and develop my arguments. Along the way I have also benefited from discussion and debate with Joanne Crawford, Tim Hall, Catherine Lupton, David Mabb, April Masten, Stanley Mitchell, Jo Morra, Ben Noys, Peter Osborne, Giles Peaker, Chris Riding, Nick Ridout, Frances Stracey, Nick Till, and Ben Watson. Invitations to present work-in-progress from Tim Clark, David Cunningham, John Goodbun, Tom Hickey, Neil Leech, Colin Mooers, and Julian Stallabrass, and also from Alex and Andrew, have enabled earlier versions of my research to be tested in sympathetic, yet challenging environments.

For their belief in the project, I am grateful to my series editors Lydia Goehr and Gregg Horowitz and to Wendy Lochner at Columbia University Press. My appreciation also goes to Christine Mortlock and Leslie Kriesel for ensuring its realization and particularly to Robert Demke for his essential guidance and his help in improving my manuscript.

Immense gratitude goes to my familyespecially to Jean Day, Brian Day, and Edna Colledgefor enduring all the uncertainties and long absences while I worked on this book.

The Arts and Humanities Research Board, Wimbledon School of Art, and the University of Leeds provided generous support to enable me to focus on writing, and, in addition, the University of Leeds has helped toward the costs of images and reproduction rights. Less formally, but no less importantly, the unique combination of peace, sanity, and hospitality at La Touche has been invaluable for securing periods of concentration necessary for writing and thinking. Earlier and shorter versions of chapters have appeared in Oxford Art Journal 22, no.1 (1999): 103118; Art History 23, no. 1 (2000): 118; and Radical Philosophy 133 (2005): 2638.

Amid reflections on the rituals, commodity kitsch, and everyday banalities of modern Japanese life, Chris Marker, in his film Sans Soleil, turns his attention to a Left-wing demonstration. The camera alights briefly on a middle-aged man (see ). The scene is shot at a rally to commemorate the birthday of a victim of a protest at the same site in the nineteen-sixties, when peasants fought to prevent an airport being built on their land. The repetitions and echoes between then and now make the occasion unreal, part of the world of appearances. The manwho we take to be one of the displaced farmerscuts a solitary figure among his youthful comrades. The airport, of course, was built. With his withering comments on the utopias of the Left, and the descent of so many of its student participants into postures and careerists, Marker certainly prods his viewers toward the melancholic conclusion that the future is already written in this experience. But the lureone of many that shape the filmserves to underscore Markers recalcitrance: he has in mind neither resignation nor defeat, but rather a reminder of how human subjects are fundamentally transformed in and through the processes of resistance. The airport is more besieged than victorious. He may be on the losing side, but once touched by the awareness and experience that comes through political protest, this mans outlook could never again be what it was.

Next page