Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For NJ, LJR, CJR

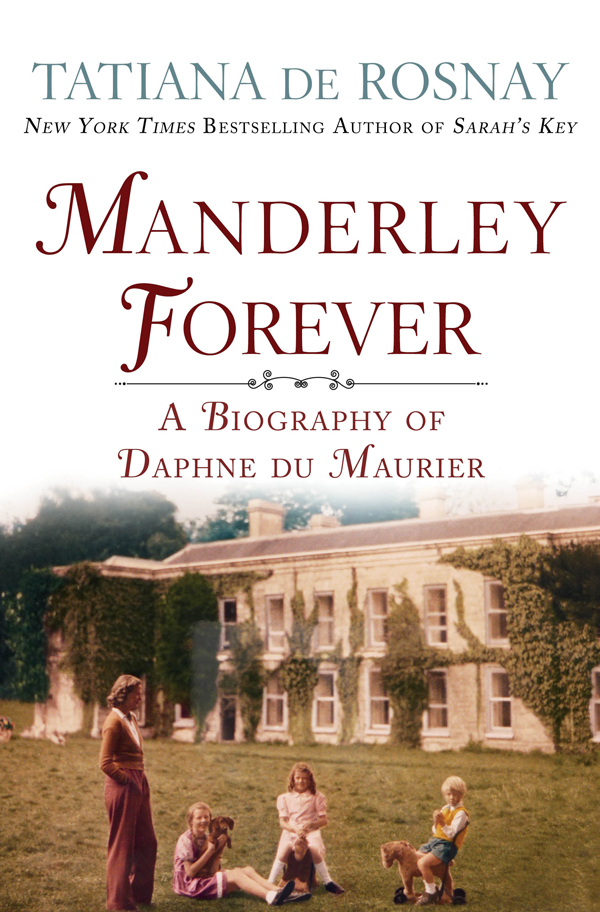

When, at the age of eleven, I first opened a copy of Rebecca, I had no idea how important that novel would become in my life. Like so many other readers before me, I was transfixed from the first, mythical sentence: Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. That book had such an effect on me that barely had I finished it before I started reading it again. I was under the spell of the du Maurier magic, her singular style, that famous psychological suspense. Before Rebecca I had already written several short storiesin English, my first languagein my school exercise books. Afterward, when I wrote other stories, I signed them Tatiana du Maurier . It was Daphne du Maurier who bequeathed me my taste (or obsession) for houses, for family secrets, for the memories held by walls. Each and every one of my novels bears her influence.

When, several years ago, Grard de Cortanze suggested I write the first French biography of my favorite novelist, I felt simultaneously honored and nervous, but I accepted the challenge. I decided to follow in her footsteps, as if I were leading an investigation, traveling from London to Cornwall, by way of Montparnassebecause she adored Paris. This literary pilgrimage allowed me to discover how Daphne du Maurier wrote, the secrets of her life, her inspiration, her work.

I described her as if I were filming her, camera on my shoulder, so that my readers could instantly understand who she was. I studied her books, her voice, the look in her eyes, the way she walked, the sound of her laughter. I met and spoke with her children and grandchildren. Around the houses that she loved so passionately I constructed the portrayal of an unusual and enchanting novelist, scorned by critics because she sold millions of books. Her macabre and fascinating world produced a complex, surprisingly dark oeuvre, far removed from the romantic novelist she was unfairly labeled as.

This book reads like a novel, but I did not invent any of it. Everything here is true.

It is the novel of a life.

People and things pass away, not places.

D APHNE DU M AURIER

The child destined to be a writer is vulnerable to every wind that blows.

D APHNE DU M AURIER

Mayfair, City of Westminster, London

November 2013

There are usually crowds of people in Regents Park. Visitors come here to walk around and admire the flower beds, see Queen Marys rose garden, take boat trips on the lake. But on this very British gray and drizzly November morning, the park is deserted.

Queen Elizabeth was born in this upmarket district; Oscar Wilde lived here, as did Handel, Somerset Maugham, and Nancy Mitford. In place of the previous centurys patrician families, the elegant Georgian buildings are now home to luxury stores and fashionable restaurants, embassies, and five-star hotels. Impossible not to notice that the people who live here or frequent these places have money. There are fur coats on display everywhere, while only the priciest, flashiest cars are parked along the sidewalks. In the London version of Monopoly, Mayfair has been the most desired space on the board for more than eighty years.

To the east of the park are the Terraces, quiet residential streets so typical of London where rows of identical terraced houses stretch out toward the horizon, perfectly symmetrical. Chester Terrace is the longest, Clarence Terrace the shortest; Park Crescent is formed in a graceful semi-circle. The one I have come to see this morning is the most imposing of all: Cumberland Terrace. I read that it dates from 1826 and comprises about thirty houses. It is located between the Outer Circle, the street that borders the park, and Albany Street.

Its not especially easy to find. Despite my map, I get lost several times before spotting its neoclassical faade from a distance. I walk through the rain toward it, impressed by its immense size and its famous Wedgwood blue pediment. I darent move any closer; I feel as if I am being watched. What could I say to one of the buildings inhabitants if they came out to ask me why I was taking photographs?

I could say, quite simply, that I am here for her, that I am following the footsteps of her life, and this is where my journey begins. Because it was here, at number 24, under these huge ivory columns, behind that white door, that Daphne du Maurier was born on May 13, 1907.

* * *

Leaving the park after going for a walk, the little girl has to pass under that gigantic-seeming arch, then climb the steps that lead to the house, on the right. The white front door matches the cumbersome pram, which Nanny cannot lift up on her own. They have to ring the doorbell so someone will come to help them. The little girl bickers with her sister Angela over who gets to press the copper-colored button first, and she has to stand on tiptoes in her Start Rite shoes in order to reach it.

Their childminder wears the same uniform, day after day. The little girl likes to look at it: the gray coat, the black hat, the veil covering her face. It is one of the maids who comes out to help Nanny with the baby carriage. She is wearing an apron and a white bonnet. They struggle to lift the pushchair with the baby inside it. From inside the carriage, Jeanne smiles, and the little girl notices the way everyone melts at her pink-cheeked sisters smile.

Inside the long entrance hall, the little girl sees coats, stoles, and capes hung on pegs; she hears the hubbub of a conversation, peals of laughter coming from the living room, to her left; she sniffs out the whiff of an unfamiliar perfume. Her heart contracts. That means there are ladies invited to lunch, that shell have to go downstairs, later, after the meal in the nursery, to say hello. This does not bother Angela; in fact, shes excited, already asking who is there with their mother. The little girl rushes upstairs, taking the steps two at a time, escaping while she can, and taking refuge in the large nursery on the top floor of the house, in that comforting warmth, near the dolls house, of the toy cupboard with two shelves (one for Angela, one for her), of the treasure chest lined with cotton cloth, of the old armchair that transforms so easily into a shipwreck run aground on a beach. She moves toward the fireplace, where flames crackle behind the fire screen. The table is set for threeNanny, Angela, and herbecause the baby still sits in her high chair to eat. She looks out toward Albany Street, toward the army barracks. Nannys voice is raised and it pursues her, repeating her name several times over. It is telling her to wash her hands before lunch. Daphne doesnt want to wash her hands, she doesnt want to eat lunch. She wants to continue looking out of the window, watching the troop of Life Guards officers as they return from their morning patrol. Her father has explained that this is the oldest regiment in the British Army, its mission to protect the king and the royal buildings. There is no way she going to miss seeing the glint of their shining armor, the plume of feathers on their helmets, the red lightning flash of uniforms. Since she stopped sleeping with Jeanne and joined her older sister on the other side of the nursery, she is woken at dawn every day by the bugle call, but this doesnt bother her at all.