The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of Robert S. Fenn

CONTENTS

LIST OF MAPS

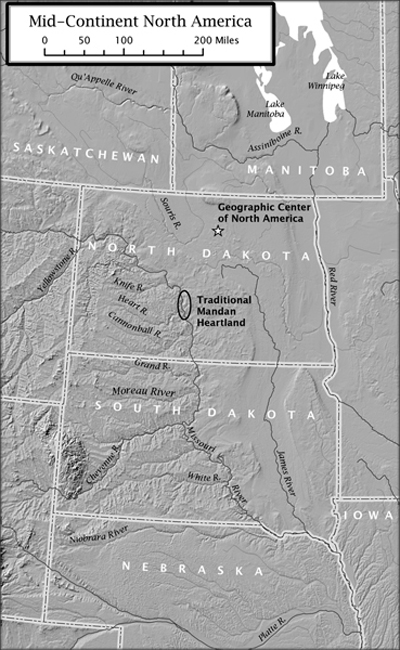

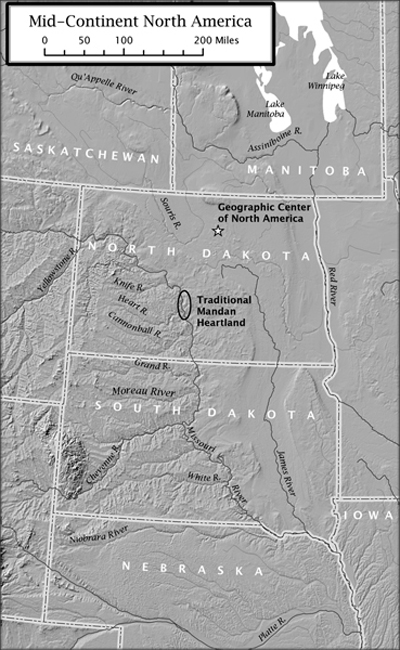

Mid-continent North America

Early plains migrations

The South Cannonball, Shermer, and Huff village sites

Pre-contact trade

Six traditional Mandan towns

Possible route of the baron Lahontan, 168889

Possible route of Henry Kelsey, 169092

Travel from the upper-Missouri villages to York Factory, ca. 1715

The Vrendrye explorations, 173843

The expansion of the horse

Franois and Louis-Joseph de la Vrendrye explore the western plains, 174243

Trading centers, 17951805

Lewis and Clark approach the Mandans, October 1804

Plains trade ca. 1800

The Knife River villages, 1823

Map 0.1

PREFACE

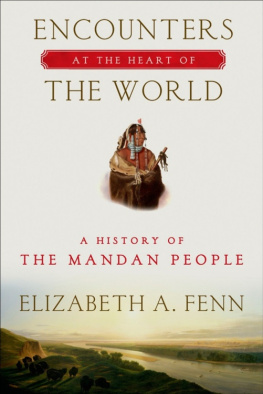

The climate of North Dakota hardly ranks among North Americas most hospitable. Plains winters are long, windy, and bitterly cold. Rainfall is fickle, and summer temperatures fluctuate wildly. Yet for the Mandan people, this landscape is home. They have lived here, at the heart of the continent, for centuries, forging a compelling presence and an enduring lifeway in the face of serious obstacles. Many of their challenges have been military, diplomatic, or commercial in nature. But others, indeed the most daunting, have been ecological. Long before the arrival of Europeans and Africans from the so-called Old World, the Mandans and their forebears had learned to accommodate the vicissitudes of drought, climate change, and competition with others for coveted resources.

These challenges persist to the present day, but the arrival of strange peoples and species after 1492 added formidable new pressures to the mix. Among the foreign species, many of the most deadly were too small to be seen. These microscopic newcomers included the viruses that convey smallpox and measles, the bacterium that causes whooping cough, and possibly the bacterium that causes cholera. Other invisible pathogens, unidentified or unmentioned in the documentary record, may likewise have reached the Mandans in these years.

While the pathogens were invisible, their effects were not. People got sick, often with horrific symptoms, and died in large numbers. Indeed, the tragic effects of those pathogens can still be glimpsed near Bismarck and Mandan, North Dakota, where the outlines of ancient Mandan settlements mark the landscape even today. Some of these town sitesonce vibrant social and commercial hubswere abandoned after epidemics had struck. Some likewise reveal a sequence of defensive ditches that contracted as populations diminished.

The visible species that remade the Mandan world included powerful horses and scurrying Norway rats. European horses arrived first, spreading north from Spanish New Mexico and the southern plains and reaching the Mandans in the early to mid-1700s. But horses did not alter the basics of Mandan existence as they did for itinerant peoples like the Sioux, Crows, Arapahos, Blackfeet, and Assiniboines. By the second half of the eighteenth century, the Mandans had simply, and profitably, added horses to the marketable goods they bartered with others. Norway rats arrived later, aboard U.S. army keelboats in 1825. The animals feasted on the great stores of maize that Mandans kept in underground caches. Multiplying rapidly, they demolished the villagers prodigious corn supplies in a matter of years.

None of these diverse species arrived in isolation, and the consequences of Old World intrusions were mixed, numerous, and unpredictable. Horses, for example, invigorated travel across the continents interior grasslands and increased interactions among plains peoples. But this also meant they helped to spread infectious diseases, since their riders sometimes carried microbial infections. Meanwhile, rats depleted Mandan corn supplies at the very time when other pressuresrelated to diverse factors including horses and steamboatsreduced the number of bison that grazed near Mandan towns. The result was a nutritional scarcity that may have made the villagers more vulnerable when pathogens struck.

By 1838, the Mandan situation was dire: Their numbers had plummeted from twelve thousand or more to three hundred at most. That they survived is testimony to their resilience and flexibility on the one hand and their traditionalism on the other.

* * *

I am concerned in this book with encounters at the heart of the worldthe Mandan name for their homelandin modern North Dakota, where the Heart River joins the Missouri River. The encounters include my own. For me, the first came during research I did some years ago on the continent-wide smallpox epidemic of 177582, which afflicted the Mandans as it did so many others. Reports of smallpox in the upper-Missouri villages had intrigued me. How could it be, I wondered, that I knew almost nothing about this once-teeming hub of life on the plains? Why do the Mandans appear in the broad history of North America only when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark spent the winter with them in 18041805? The accounts I read confirmed my suspicion that significant holes persisted in our knowledge of early America. Places we knew remarkably little about had once cradled prosperous human settlements. The more I learned, the more I sensed that the Mandan story provided an alternative view of American life both before and after the arrival of Europeans.

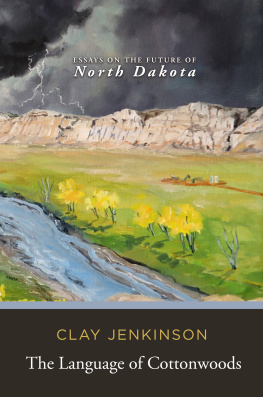

It nevertheless took a trip to North Dakota to convince me. How could I write about a place I had not yet seen? Geography, landscape, and natural history have always appealed to me; they creep inexorably into my thinking and writing. So in August 2002 I went to North Dakota for the first time, just to see if it felt right.

In a grime-covered red Pontiac, I crisscrossed the western half of the state, where I was captivated by the rolling plains, the crumpled badlands, and the reassuring presence of the Missouri River, the geographic reference point to which I always returned. At Lake Sakakawea, formed by the completion of the Garrison Dam in 1953, I followed the Missouris shoreline southeast across the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. Fort B, as the locals call it, is the modern-day home of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples, officially designated the Three Affiliated Tribes. The center of tribal life is New Town, a sprawling community of wide streets, modest homes, and motley storefronts on the east shore of the lake. Here I filled my gas tank at the Cenex station and stocked up on groceries at the Super Valu market.

New Town was dusty and quiet on that first visit in 2002. Little did I know then that the community was about to face a twenty-first-century upheaval. Just a few years later, the steady rumble of tanker trucks along Main Street marked New Towns transformation into an edgy boomtown, with resources strained to the limit. Frackingthe extraction of underground oil by hydraulic fracturinghad come to Fort Berthold. But in 2002, there were few visible signs of this impending turn of fortune.

From New Town, I drove two miles west on Highway 23, past Crow Flies High Butte and across the rickety Four Bears Bridge, soon to be replaced by a more accommodating span of the same name. Bridge and butte alike honor the memory of notable Indian leaders. On the far bank of the Missouri, really of Lake Sakakawea, I eyed the beige-and-brown tribal administration building from afar. Who was I to waltz in and announce I had come to write Mandan history? I wandered through the dim, boxy sprawl of the 4 Bears Casino, eerily animated by a cacophony of flashing lights and electronic sounds. I stayed longer at the nearby Three Affiliated Tribes Museum, where I studied an array of exhibits that as yet made only partial sense to me. I also met the museums director, Marilyn Hudson, a steadfast guardian of her peoples past and a font of living history.