Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher was one of the great food writers of the twentieth century. Born in 1908 in Albion, Michigan, Fisher grew up in Whittier, California, and was educated at Illinois College, Occidental College, and UCLA, and at the University of Dijon in France. She travelled to, and lived in Europe throughout her adult life. The author of numerous books, magazine articles, novels, and a translation of Brillat-Savarins The Physiology of Taste, Fisher is best remembered for her gastronomical works and the autobiographical nature of her writings about people, places, and food. M.F.K. Fisher died in 1992.

A LSO BY M.F.K. F ISHER

by M.F.K. Fisher

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House of Canada Ltd., Toronto. Originally published in hardcover as part of Two Towns in Provence in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 1978.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

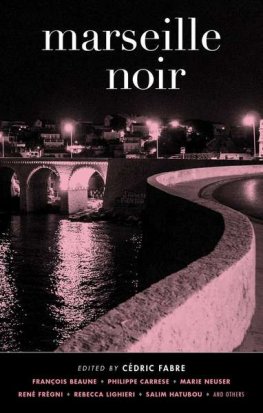

One of the many tantalizing things about Marseille is that most people who describe it, whether or not they know much about either the place or the languages they are supposedly using, write the same things. For centuries this has been so, and a typically modern opinion could have been given in 1550 as well as 1977.

Not long ago I read one, mercifully unsigned, in a San Francisco paper. It was full of logistical errors, faulty syntax, misspelled French words, but it hewed true to the familiar line that Marseille is doing its best to live up to a legendary reputation as world capital for dope, whores, and street violence. It then went on to discuss, often erroneously, the essential ingredients of a true bouillabaisse! The familiar pitch had been made, and idle readers dreaming of a great seaport dedicated to heroin, prostitution, and rioting could easily skip the clumsy details of marketing for fresh fish.

Feature articles like this one make it seem probable that many big newspapers, especially in English-reading countries, keep a few such mild shockers on hand in a back drawer, in case a few columns need filling on a rainy Sunday. Apparently people like to glance one more time at the same old words: evil, filthy, dangerous.

Sometimes such journalese is almost worth reading for its precociously obsolete views of a society too easy to forget. In 1929, for instance, shortly before the Wall Street Crash, a popular travel writer named Basil Woon published A Guide to the Gay World of France: From Deauville to Monte Carlo (Horace Liveright, New York). (By now even his use of word gay is quaintly nave enough for a small chuckle.)

Of course Mr. Woon was most interested in the Cote dAzur, in those far days teeming and staggering with rich English and even richer Americans, but while he could not actively recommend staying in Marseille, he did remain true to his journalistic background with an expectedly titillating mention of it:

If you are interested in how the other side of the world lives, a trip through old Marseillesby daylightcannot fail to thrill, but it is not wise to venture into this district at night unless dressed like a stevedore and well armed. Thieves, cutthroats, and other undesirables throng the narrow alleys, and sisters of scarlet sit in the doorways of their places of business, catching you by the sleeve as you pass by. The dregs of the world are here, unsifted. It is Port Said, Shanghai, Barcelona, and Sidney combined. Now that San Francisco has reformed, Marseilles is the worlds wickedest port.

(Mr. Woons last sentence, written some fifty years ago, is more provocative today than it was then, to anyone interested in the shifting politics of the West Coast of America.)

While I either accept or deplore what other people report about the French town, and even feel that I understand why they are obliged to use the words they do (Give the public what it wants, etc., etc.), I myself have a different definition of the place, which is as indefinable as Marseille itself: Insolite.

There seems to be no proper twin for this word in English; one simply has to sense or feel what it means. Larousse says that it is somewhat like contrary to what is usual and normal. Dictionaries such as the Shorter Oxford and Websters Third International try words like apart, unique, unusual. This is not enough, thoughnot quite right. Inwardly I know that it means mysterious, unknowable, and in plain fact, indefinable.

And that is Marseille: indefinable, and therefore insolite. And the strange word is as good as any to explain why the place haunts me and draws me, with its phoenixlike vitality, its implacably realistic beauty and brutality. The formula is plain: Marseille = insolite, therefore insolite = Marseille.

This semantical conclusion on my part may sound quibbling, but it seems to help me try to explain what connection there could possibly, logically, be between the town and mewhy I have returned there for so long: a night, ten nights, many weeks or months.

Of course it is necessary to recognize that there is a special karma about Marseille, a karmic force that is mostly translated as wicked, to be avoided by all clean and righteous people. Travellers have long been advised to shun it like the pesthole it has occasionally been, or at best to stay there as short a time as possible before their next ship sets sail.

A true karmic force is supposed to build up its strength through centuries of both evil and good, in order to prevent its transmigration into another and lesser form, and this may well explain why Marseille has always risen anew from the ashes of history. There seems to be no possible way to stamp it out. Julius Caesar tried to, and for a time felt almost sure that he had succeeded. Calamities caused by mans folly and the gods wrath, from the plagues ending in 1720 to the invasions ending in the 1940s, have piled it with rotting bodies and blasted rubble, and the place has blanched and staggered, and then risen again. It has survived every kind of weapon known to European warfare, from the ax and arrow to sophisticated derivatives of old Chinese gunpowder, and it is hard not to surmise that if a nuclear blast finally leveled the place, some short dark-browed men and women might eventually emerge from a few deep places, to breed in the salt marshes that would gradually have revivified the dead waters around the Old Port.