Marseille Mix

William Firebrace

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

Preface

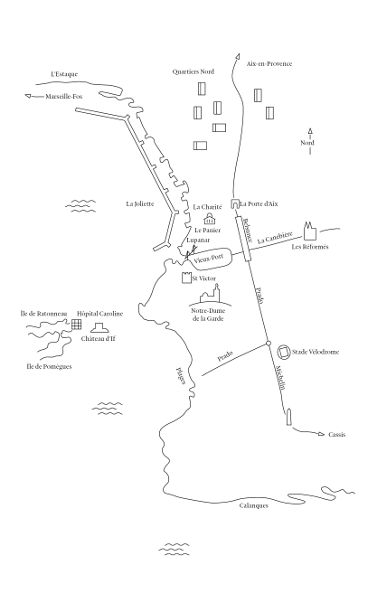

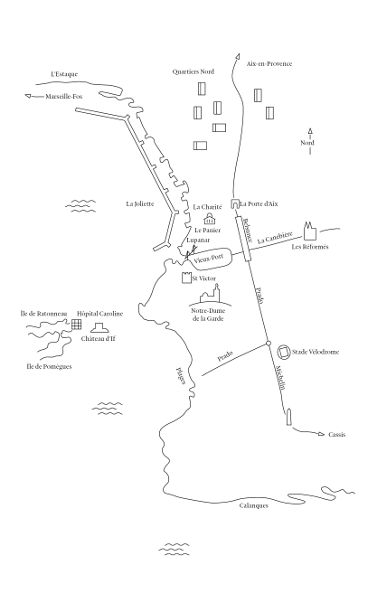

There are supposed to be seven hills in Marseille, just as there are in Rome and Istanbul, but if you were to count them you could find a few more, or perhaps just settle for an undulating terrain with no clear hills at all. There are also meant to be seven seas in the Mediterranean, but they all flow into one another and nobody agrees as to the precise identity of any of them. Perhaps seven just implies many. There are also seven sections to this book, seven views of the city. The English call the city Marseilles (as a plural), and for once they are right: there are many Marseilles, or many versions of Marseille. This book is written from the point of view of an outsider, and is defined not only by an outsiders insights and perceptions, but also by an outsiders mistakes and weakness for tall stories and partial truths. Since Marseille itself is a city of outsiders, or rather of different degrees and conditions of inside and outside, where no one is completely outside or completely inside, the city and book share some of the same qualities.

Elsewhere

M arseille is a series of invented cities, living as stories and images, sometimes original, sometimes borrowed, strung together without too much concern for the joints and overlaps. There are any number of semi-fictional versions of Marseille, competing with one another and often contradictorythe comic seaside village whose inhabitants doze out in the sun; the haven of gangsters and whores with its carefully staged shoot-outs; the magnificent port, former gateway to the east, now mostly derelict; the multicultural city of immigrants and outcasts, colourful or threatening or both together; the new city of leisure, capital of the would-be land of Provence-California; the city of grainy music videos, with youths shooting up outside mournful housing blocks; the dull bourgeois provincial town where nothing ever happens; the mysterious unknowable city of the Mediterranean coast, with its hills and limestone coves. All these cities are found in the many books and films about Marseille, each one based on some actual aspect of the city, but also a projection, an overstatement or deliberate distortion, for somehow Marseille more than most cities lends itself to myths and exaggerations. With every characterisation the feel of Marseille turns and shifts, the city moves from dangerous to harmless, from healthy to sick, from light to dark. Each of these images creates a different city, a city that is never precisely sited, a city that is always elsewhere.

Galjade (Provenal: galja), gallantry, a joke, a fantastic invented story

Blaguer (Provenal: blaga), chatter, talk abundantly

Even an invented story, however, has a basis in some kind of actual place. Somewhere in amongst these images is the actual city, beside the sea, of bricks, stone and concrete, of wharves, ships, cranes and warehouses, of houses and housing blocks. The construction of this city is surprisingly solid, direct and immediate, almost brutally real. The two, the invented and the actual, interact and influence one anotherthe actual forming the basis for the invented, but the invented also changing the way the actual is seen and sees itself. It is difficult to know which is the original and which is the double, a common theme in the city.

With both eyes closed you can see images from the various narratives all mixed up together, overlaid on top of one another, an impossible city, an ever-extending urban galjade. You can imagine yourself back once more in the actual city, in that curious, very particular light, along the long narrow streets which run straight across the hills, the mixture of people pushing by, the strong and defiant, compelling feeling of being in another place.

The only real way to arrive at Marseille is by boat, approaching gently from across the sea, but except for the ferries from Africa and Corsica few boats arrive in Marseille today. A less diverting but easier method is to arrive from inland, by train. As it moves south, the train speeds for what seems like hours across a landscape of parched hills and plains. Inside, the railway carriage is cool, quiet and comfortable. The seats, the tables, the light, the harmonious colours are all elegantly designed. The passengers mostly ignore one another, absorbed in their individual journeys. The train passes through a long tunnel. There seems to be a moment of pause, nothing happening, just waiting. The train emerges from the tunnel. Sudden light. Tower blocks, low buildings, sheds, factories, roads. Another European city. Yellow-grey colour. Nowhere in particular. Except that not far away there appears the grey-blue background of the sea.

There are several exits from Marseille railway station. Perhaps the image a visitor has of the city is determined by the exit they take, as though the very first experience remains the strongest, burnt onto the mind like light onto a slow photographic film. Later experiences may modify this first moment, but can never erase it. Or perhaps the image of the city is already decided before the visitor even arrives, through the rumours and stray information which tumble carelessly through the world, through the pictures and films they have seen. And perhaps these vague impressions subconsciously determine which exit the visitor will take, suggesting one route rather than another, gently steering them to the left of the newsstand rather than the right, pressing them to follow without much thought this group of people rather than others, so that without knowing it the visitor arrives at one version of the city rather than another, and the rest is already decided. The usual exit to the left of the newsstand in the citys main Saint-Charles station takes the traveller out onto the grand theatrical steps leading down towards the centre of Marseille. Standing at the top of the steps, surprised to be out of the dim light of the station, most visitors pause for a moment to take in a view of the city. The view stretches down the steps, across the statues of women representing the former colonies of Asia and Africa, then along the boulevard dAthnes, with its dilapidated nineteenth-century houses, across la Canebire, across the bourgeois houses of the 6th district to the hills and to the sky beyond. Up to the right, on the hill, is the church of Notre-Dame de la Garde, also known as

Next page