POETIC MACHINATIONS

POETIC MACHINATIONS

allegory, surrealism, and postmodern poetic form

Michael Golston

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2015

Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgment is made to reprint the following: Excerpt from John Ashbery, The Tennis Court Oath, 1962 by John Ashbery. Reprinted by permission of Wesleyan University Press.

From a Photograph. By George Oppen, from New Collected Poems, copyright 1962 by George Oppen. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

The Red Wheelbarrow. By William Carlos Williams, from The Collected Poems: vol. 1: 19091939, copyright 1938 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Excerpt. By Susan Howe, from Pierce-Arrow, copyright 1999 by Susan Howe. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Exerpts from Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, copyright 2002. Reprinted by permission of University of California Press.

All Louis Zukofsky material copyright Paul Zukofsky; the material may not reproduced, quoted, or used in any manner whatsoever without the explicit and specific permission of the copyright holder. Reprinted by permission of New Directions and Wesleyan University Press.

A version of was published as Petalbent Devils: Louis Zukofsky, Lorine Niedecker, and the Surrealist Praying Mantis, Modernism/Modernity 13, no. 2 (2006): 325347. Copyright 2006 The Johns Hopkins University Press. Reprinted with permission by The Johns Hopkins University Press.

A version of was published as At Clark Coolidge: Allegory and the Early Works, American Literary History 13, no. 2 (2001): 295316.

Part of was published as Mobilizing Forms: Lyric, Scrolling Device, and Assembly Lines in P. Inmans nimr, in Mark Jeffries, ed., New Definitions of Lyric: Theory, Technology, and Culture, 315 (Levittown, Pa.: Garland, 1998).

Special thanks to

Peter Inman, for permission to quote from Think of One, copyright 1986.

Myung Mi Kim, for permission to quote from Dura, copyright 1998.

Craig Dworkin, for permission to quote from Strand, copyright 2005.

Charles Bernstein, for permission to quote from A Poetics, copyright 1992.

Clark Coolidge, for permission to quote from Own Face, copyright 1978; Polaroid 1975; Quartz Hearts, copyright 1978; Smithsonian Depositions/Subject to a Film, copyright 1980; Space, copyright 1970; The Maintains, copyright 1974.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Golston, Michael.

Poetic machinations : allegory, surrealism, and postmodern poetic form / Michael Golston.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16430-6 (cloth : acid-free paper)ISBN 978-0-231-53863-3 (ebook)

1. American poetry20th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Allegory. 3. Surrealism (Literature) 4. Poetics. I. Title.

PS323.5.G65 2015

811'.509dc23

2014045626

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Cover Design: Jennifer Heuer

This ones for Cork.

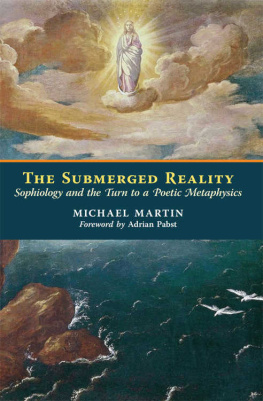

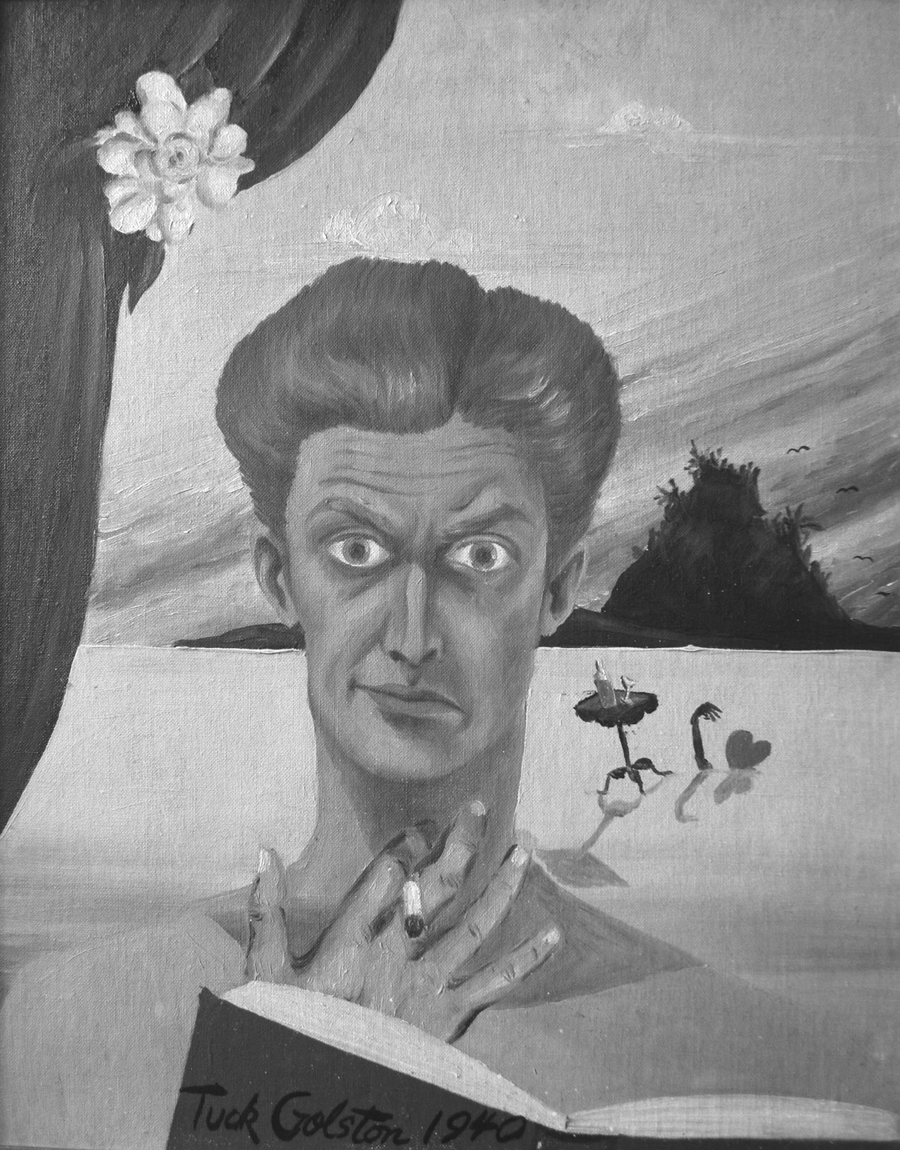

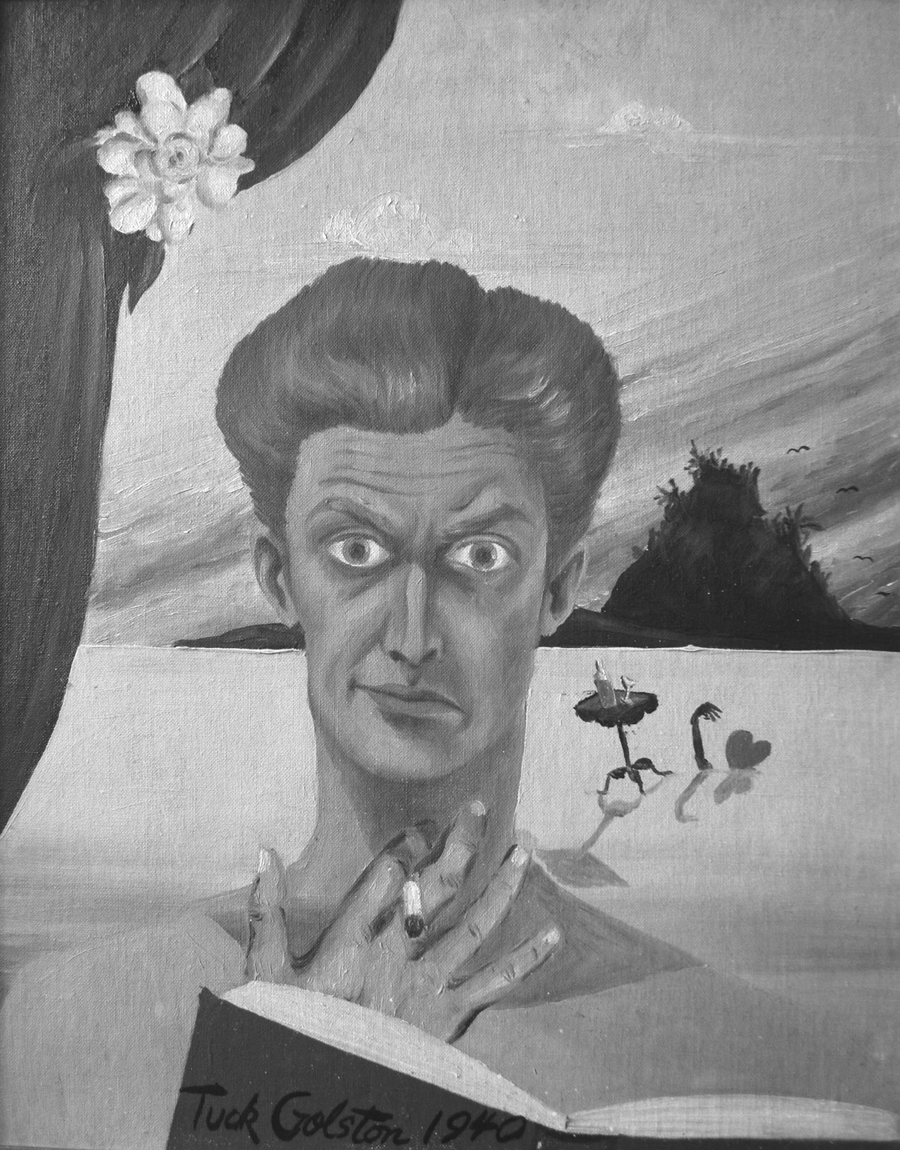

Self-portrait, by the authors father, Lawrence (Tuck) Golston (1940)

CONTENTS

The great misunderstandings. Yes. Thats a whole history of art, isnt it?

Clark Coolidge, An Interview with Clark Coolidge

This book sets out to describe a line or, perhaps more accurately, a practice of postmodern American poetry that I maintain is fundamentally allegorical and that early on finds its inspiration in certain aspects of surrealism, to which it later maintains varying degrees of affiliation. The trope plays a key role in American avant-garde poetry in nearly every decade from the 1930s to the present, and poets as distant in time and style as the objectivist Lorine Niedecker, the language writer Lyn Hejinian, and the conceptualist Craig Dworkin can, I argue, be classified as allegorists. During this same ninety-year period, allegory also consistently appears in critical discussions and period histories: it is alternately pronounced the armature of modernism (Walter Benjamin, Angus Fletcher); the characteristic signature of postmodernism (Fredric Jameson, Craig Owens); and the principal mode of a kind of post-postmodernism (Robert Fitterman and Vanessa Place). Every time a new direction in poetry is announced or discerned over the past hundred years, the trope is invoked: some configuration, whether critical or creative, of the literary avant-garde periodically declares allegory its principal mark of difference.

This claim immediately calls for qualification: American avant-garde writers have more often than not condemned allegory as artificial, antique, formalist, reactionary, painterly, European, or otherwise degraded. The most familiar branches of experimental or innovative poetry in Americathat is, those deriving from Ezra Pound and imagism or from the early The matter is complicated by the fact that allegory has never entirely lost its early affiliations with surrealism, although the philosophical entanglements of the two are problematical: they share certain formal strategies, but not all surrealism is allegorical, not all allegory surreal. The ongoing dynamic between the rhetorical trope and the art movement is part of what I deal with in this book.

The trajectory I trace goes like this: carried to American shores along with surrealism during the early 1930s, allegory is embraced for a time by Lorine Niedecker and then largely dropped until rediscovered by John Ashbery in the late 1950s. Clark Coolidge picks up the impulse in the 1960s, and it travels on to certain of the language poets in the 1970s and 1980s and into the works of writers such as Susan Howe and Myung Mi Kim in the 1980s and 1990s, after which it winds up informing present-day conceptualist poetics.with effacement (1981b, viii); or, as Deborah Madsen puts it, echoing an older modernist formulation, allegory registers a dissociation of sensibility (1996, 126), appearing, for instance, as the individual genius valued by Romanticism gives way to the culturally constituted discursive subject prized by poststructuralism (123). Generally speaking, she says, allegory is conceived as a way of registering the fact of crisis (119).

Critics thus often strike a moralizing note, construing history as a tragic narrative of ongoing loss while mourning the passing of a mythic time when language supposedly had more power. Maureen Quilligan writes that allegory as a form responds to the linguistic conditions of a culture (1979, 19): due, she says, to the context of a renewed concern for language and its special potencies... we have regained not only our ability to read allegory, but an ability to write it (204), and she goes on to declare that allegory will flourish in a culture that grants to language its previous potency to construct reality (236). But was language previouslyor for that matter evermore potent? And did we at some point really lose our ability

Next page