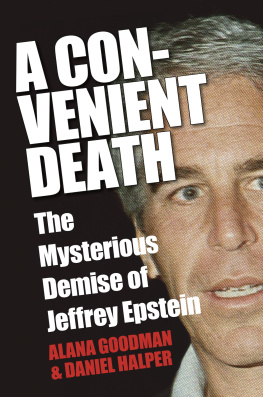

ALICE GOODMAN is a poet, librettist, and Anglican priest. She serves as rector for several parishes in Cambridgeshire, England. JAMES WILLIAMS teaches English and American literature at the University of York in the United Kingdom. HISTORY IS OUR MOTHER Three Libretti Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, The Magic Flute ALICE GOODMAN Introduction and historical notes by JAMES WILLIAMS NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com

Nixon in China copyright 1987 by Alice Goodman

The Death of Klinghoffer copyright 1991 by Alice Goodman

The Magic Flute copyright 1991 by Alice Goodman Introduction and historical notes copyright 2017 by James Williams All rights reserved. Cover art: Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Stage set for Mozarts

Magic Flute, 1815 Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Goodman, Alice. | Contains (work): Goodman, Alice.

Nixon in China. | Contains (work): Goodman, Alice. Death of Klinghoffer. | Contains (work): Schikaneder, Emanuel, 17511812. Zauberflte. English.

Title: History is our mother: three libretti : Nixon in China, The death of Klinghoffer, The magic flute / by Alice Goodman ; introduction by James Williams. Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2017] | Series: New York Review Books classics Identifiers: LCCN 2016037111 | ISBN 9781681370644 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: OperasLibrettos. | Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 19131994Drama. | LCGFT: Librettos. | LCGFT: Librettos.

Classification: LCC ML49.G66 H57 2017 | DDC 782.1/0268dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016037111 ISBN 978-1-68137-065-1 v1.0 For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

In Memory of Geoffrey William Hill 19322016

INTRODUCTION

History is our mother, we/Best do her honor in this way, sings Richard Nixon to Mao Tse-tung in Alice Goodman and John Adamss opera

Nixon in China (1987). The presidents voice is recast in an operatic mold, but not bent out of shape. We hear the signature accents of the man: his grandiose but fragile optimism, the honorable self-image accompanying the brutal instinct for power. This historic mission is how, standing on the White House lawn in 1972, Nixon trumpeted his impending visit to China, going on to say if there was a postscript that I hope might be written with regard to this trip, it would be the words on the plaque which was left on the moon by our first astronauts when they landed there: We came in peace for all mankind. Nixons appeal to history as our mother is a similar pitch for brotherhood-of-man rapprochement (Let us join hands, make peace for once), but his chosen metaphor is, like himself, trickier than it seems. It is no simple matter to beor to havea mother: the cultural archetypes of motherhood run from Medea to the Blessed Virgin, Mother Courage to Norma Bates and Mama Rose.

There are more kinds of relationship here than can easily be named by a single word, a fact Chairman Mao exploits mercilessly in his response: History is a dirty sow: If we by chance escape her maw She overlies us. Maos language, in Goodmans hands, is an echo chamber of allusions: James Joyces Portrait of the Artist (Ireland is the old sow that eats her farrow) meets the remark variously attributed to Saint Augustine and Dorothy Day, among others, that The Church is a whore, but shes still our mother. Mao picks up Nixons metaphor and complicates it, but he does not deny it. History is our mother, and what a mother. The idea returns when Chiang Ching (Madame Mao), the terrible self-appointed mother of the nation, sings: At the breast/Of history I sucked and pissed. And again, when she sings of the assembled politicians who think they can woo history with their charm: Well teach/These motherfuckers how to dance. Chiang Ching is one among a wonderful and fearsome variety of mothers in Goodmans work: Pat Nixon, Marilyn Klinghoffer, the Queen of the Night.

In the third libretto in this volume, a translation of the sung sections of The Magic Flute for the Glyndebourne Festival in 1991, Goodman renders the Queens famous aria Der Hlle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen in terms that foreground the maternal wound: Let my child tear Sarastros body open, Or let her curse the day that she was born. W. H. Auden and Chester Kallmans artfully arch 1955 translation makes the violence to which the Queen urges her daughter, Pamina, emphatically phallic and male (Impale his heart or you are not my child [italics mine]), but Goodman wants us to hear the appeal to the pain of childbirth. Curse the day that she was born is a clich that suddenly and uncomfortably comes alive after tear Sarastros body open. Giving birth is a tearing open of the body, says the Queen: I have suffered, and you owe me a debt.

Goodmans Magic Flute plays so joyfully with the kitsch and sententiousness of Emanuel Schikaneders original (Papagena! /Honey! Baby! My old china!) that this stroke of cruelty jumps out all the more sharply. It comes as no surprise in an opera as exaggeratedly misogynistic as The Magic Flute that maternity is something problematic, but for Goodman it becomes an embodiment of the trauma of history, a way of staging our dependency on the past. Goodmans Queen of the Night calls to mind her operatic daughter, Chiang Ching, who brutalizes a young female dancer in a harangue in which brilliant turns on the line endings of the verse keep the mothers sufferings always in view: I cut my teeth upon the land And when I walked my feet were bound On revolution. Foot-binding, a fashionable mutilation of womens bodies, was still practiced in 1914 when Chiang Ching was born, but she was not a member of the wealthy, nonlabor class for whom it was viable. Her feet were bound for a different task, she says, and though it was an earlier Madame Mao who took part in the Long March, that great hegira of the Chinese Revolution, she impresses both maternal suffering and the weight of Communist history on her cowering substitute daughter. The story of the origins of Goodmans libretti and the historical imagination at work in them are finely intertangled.

When Nixon in China premiered at Houston Grand Opera in October 1987, its creatorsthe then little-known poet Alice Goodman, and the somewhat better-known composer John Adams and director Peter Sellarswere staging yesterdays news. The presidential visit to China in 1972 was a diplomatic coup for the United States at a time when geopolitical stakes were high. In the background is the Vietnam War and the ongoing peace talks in Paris: Nixon hoped that a breakthrough in relations with China would undermine support for the Vietcong and strengthen his hand against the USSR, as well as lend him cachet among the American electorate. Still to come, but present in the audiences mind, is the catastrophic scandal of Watergate.[] The president, Mrs. Nixon, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger arrive in China on a cold morning in February. Mrs. Mrs.

Nixon is given a personal tour of the city, and the first couple are received by Chiang Ching who treats them to a command performance of her ideologically pure ballet The Red Detachment of Women. In the short third act, the central characters are left trying to digest the events of the previous days. History and politics are the stuff of opera, but few operas deal with happenings quite so fresh in the collective memory. (Beethovens

New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Nixon in China copyright 1987 by Alice Goodman The Death of Klinghoffer copyright 1991 by Alice Goodman The Magic Flute copyright 1991 by Alice Goodman Introduction and historical notes copyright 2017 by James Williams All rights reserved. Cover art: Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Stage set for Mozarts Magic Flute, 1815 Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Goodman, Alice. | Contains (work): Goodman, Alice.

New York THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Nixon in China copyright 1987 by Alice Goodman The Death of Klinghoffer copyright 1991 by Alice Goodman The Magic Flute copyright 1991 by Alice Goodman Introduction and historical notes copyright 2017 by James Williams All rights reserved. Cover art: Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Stage set for Mozarts Magic Flute, 1815 Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Goodman, Alice. | Contains (work): Goodman, Alice.