This is a story I have waited for thirty years to tell. When I first heard it, I was a producer working on ITVs investigative current affairs series, World in Action. Like most people at the time, I was preoccupied with the conflict between Britain and Argentina over the invasion by the military junta of the Falkland Islands. When the Argentines landed, it had seemed like a relic of a bygone age, an echo of our colonial past more like 1882 than 1982.

It is fair to say that when Britain woke up to the amazing news that we had lost the Falklands, the reaction of most people was to ask what are they? and where? On the day of the invasion, ITVs evening news magazine programme in the north-west of England, Granada Tonight, sent out reporters to ask people in the street where they thought the Falklands were. Just off the coast of Scotland? was the most common speculation. Yes of course they are off the coast of Scotland, quipped the presenter back in the studio, the trouble is that they are some 8,000 miles off the coast of Scotland, and only about 300 miles off the coast of Argentina.

Humour quickly turned sour as the television news carried pictures of disarmed Royal Marines lying face down in the street with Argentine soldiers standing over them. Falkland Islanders, we were informed, felt every bit as British as do Cornishmen or the Welsh probably more so.

Britain and the world watched in amazement as the Royal Navy assembled a Task Force, consisting of ships that most of us had no idea we still possessed, and cheering crowds lined the jetties and coastline as the armada set off to the far end of the world to free our good people from beneath the jackboot of the tyrant. Certainly some jumped-up band of tin-pot generals with too many medals on their chests and too much gold braid on their epaulettes could not be allowed to cock a snook at the British Empire. Just exactly who did they think they were dealing with here?

Three months later, the war was over and our boys were either back or on their way back. Or at least, most of them were. It had been a close-run thing, and far closer than any of us had realised at the time. There was triumph in the popular headlines, there were services of thanksgiving, and Mrs Thatcher (not Her Majesty the Queen) took the salute at the military march-past. But then questions began to be asked. Had the war really been unavoidable? Aside from the fact that it could and should have been anticipated and averted, had it really been necessary to fight at all? Could the matter not have been resolved peacefully through negotiation? Did 649 Argentines and 258 British soldiers, sailors and airmen have to die?

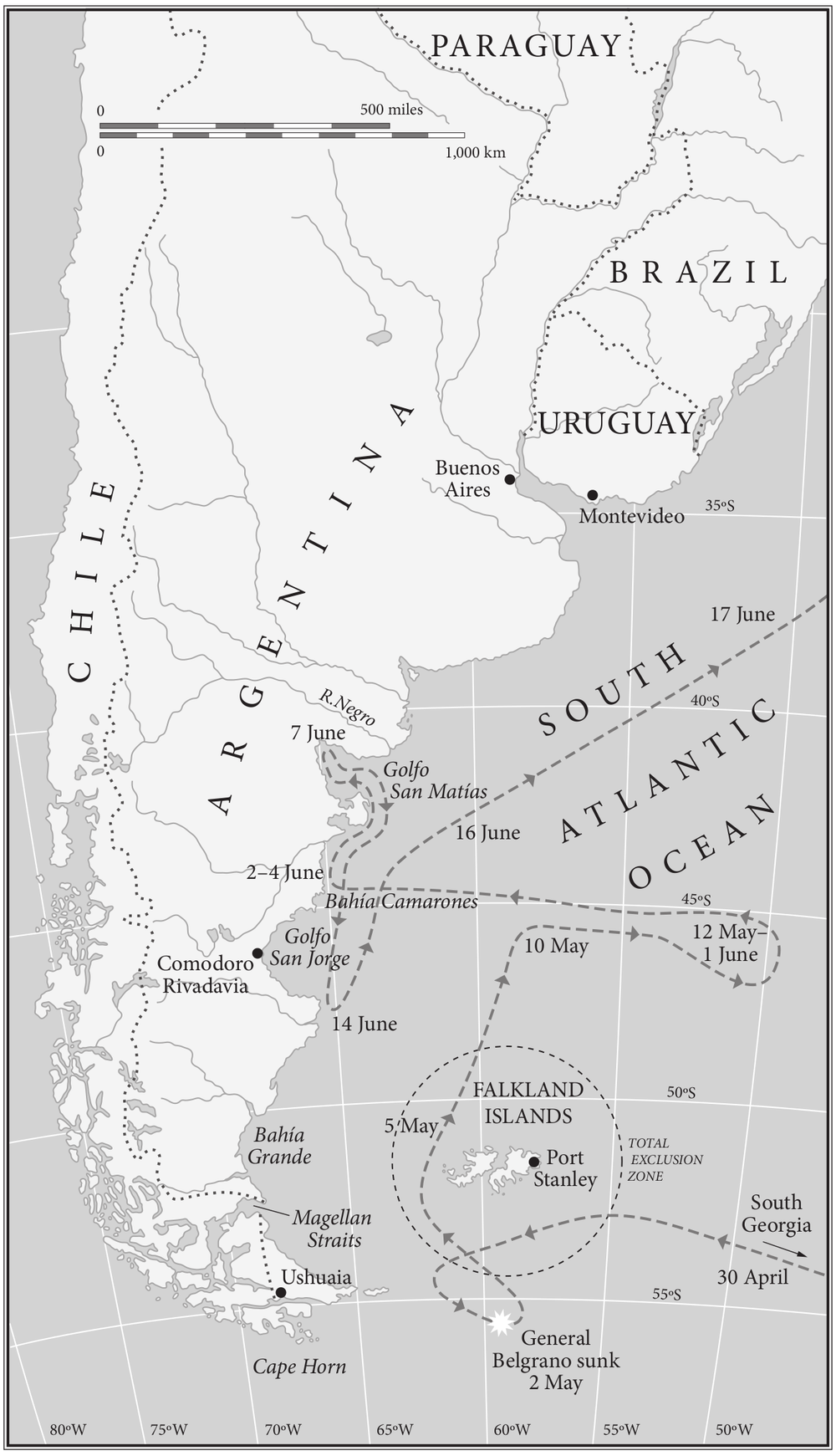

Much of the controversy centred on the sinking of the Argentine cruiser ARA Belgrano with the loss of 323 men. It was widely agreed that this action, by the British hunter-killer submarine HMS Conqueror, had been the act which had made inevitable an all-out war in the South Atlantic. Not only had it sent the Argentine ship to the bottom of the ocean, but with it had gone any prospects of success for the peace negotiations which were being brokered at the time by Peru with the help of the Americans.

On the face of it, the circumstances of the sinking had been straightforward enough. She was an enemy warship, she was at sea, she was escorted by two destroyers, the British had the chance to sink her, and they did. GOTCHA! yelled the front-page headline of the Sun, and by jingo we had taught the Argies a lesson. But, as often happens in political history, it was not so much the original act which was now causing such disquiet, it was the fact that the government had chosen to lie about it. Week by week, revelations began to emerge showing the differing accounts of the military men who had been there, and the politicians back home who had presented the official version of the sinking. There were discrepancies over just about every aspect of the action, including the first time that the Argentine cruiser had been spotted, its actions in the hours before the attack, its position, its orders, and its course and speed at the moment it was hit by two Mark 8 torpedoes, wracked by explosions and consigned to the sea-bed.

Then, when it already seemed inescapable that the government was covering up something very murky, the Defence Secretary told a stunned House of Commons that a log-book from HMS Conqueror was missing. The control room log-book contained details of the course, depth and speed of the submarine, and its loss was only discovered more than two years after the war, when a civil servant went in search of it in order to try to answer a question from an MP. Immediately it was widely assumed that the log-book contained information that would contradict some aspect of the governments account of the sinking, and had not been lost at all.

An officer serving in the Conqueror, whose personal diary had fuelled much of the controversy about the attack on the Belgrano, was accused of stealing the log-book. If indeed he had misappropriated it, then it could not have been a government cover-up. The mystery deepened. The hunt for the author of the diary, and the thief, was on. By this time I was working on the World in Action programme and I was one of a number of journalists on the trail of the vanishing log-book and all that it implied.

One evening I found myself in company with a small number of submariners from HMS Conqueror, and in the course of several hours a story emerged which, even now as I recall it, I find utterly extraordinary. It is a tale as incredible as the exploits of James Bond, straight out of John le Carr, a story from the wildest part of the front line of the Cold War which was still, at that time, very much liable to go hot at any moment.

My journalistic instincts were aroused and I spent a sleepless night wondering how best I could tell the story I had just heard. In the small hours of the morning, however, I realised that this particular episode could not be made public. I was, and still am, all in favour of freedom of information, and certainly freedom of any information which is kept secret merely because it embarrasses the government. However, this, if anything was, seemed like a genuine military secret: a matter of national security.

At that time I was thirty years old. I thought about the thirty-year rule under which national secrets can be reviewed to see if the passage of time has allowed them to be published. When that came around I would be sixty, and maybe have some time on my hands. In the thirty years since then I have indeed produced three separate World in Action programmes dealing with different aspects of the Falklands War, I have been a documentary maker, a commissioning editor, and Chief Executive of ITV. Eventually I left to start my own TV production company where I executive-produced series such as