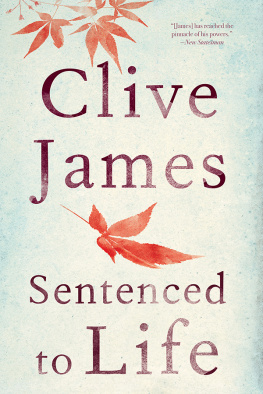

CLIVE JAMES

Somewhere Becoming Rain

Collected Writings on Philip Larkin

Contents

To Claerwen, who saw

that these pieces ought to be a book

Introduction

The arrangement of this book might seem episodic at first but it was lamentably true that Philip Larkin, who threw a tall shadow by the time of his death, was nevertheless obliged to die by inches, with fist-fights raging in the graveyard. I wish the battle had been fought and won, and his soul might rest easy. But the struggle continues. People of surprisingly high intelligence have managed to convince themselves that Larkins poetry didnt amount to much at all. And presumably, to them, it doesnt, although their dismissal of him makes you wonder whose poetry they think does matter, if his does not. Sometimes they tell us, and we think that he has had a lucky escape. But it might have been an escape all the way to oblivion, if the total audience for poetry had been easier to persuade.

Luckily it was not, and the true story behind this episodic book is the gradual but unstoppable increase of his prestige as it grew to match the common readers love. He was just an ordinary man too often he thought of himself as even less than that but behind his show of diffidence (he was still on the threshold of a stammer even at the end) there was a highly developed sense of duty to his gift. Indeed that sense of duty shaped his life, sometimes to the point of distortion. Would he really have put such ingenuity and effort into hoodwinking the several women who loved him if he had not realised that his need for affection was matched by an equally consuming need to be alone?

And being alone meant being alone with the next piece of writing, even when it was just a column about a few jazz discs that he privately thought should be left in front of the two-bar radiator until they melted. When the next piece of writing was a poem (sometimes a poem that had been in the works for years) nothing else counted. Nothing was going to take his attention away from those few lines that were searching for the paths by which they could become a few more, or even just one more, or even enough sweat for tonight no more.

He was trained up for it. At the end of this book we will find the great double origin of his gift for creative solitude. If the letters to and from his father do not precisely reveal the old man as the Nazi sympathiser that Larkins detractors are still hopefully expecting to take the stage, they do reveal that Larkins father blessed him with a long close-up of what it looked and sounded like to be concerned with English grammar and its correct usage; and his mother emerges as the great analyst of the grocers shop shelves who shared and helped to shape his taste for the commonplace. Here is the chance for the reader, especially the male reader, to overcome his Hemingway complex. The chances are that he wont spend much of his future diving out of an aircraft and sprinting into battle. More likely he will be hovering between the supermarket display cases checking out the rising price of Marmite. Larkins mother gave her stammering son the assurance to find his way through the ticketed maze, and his father gave him the precision of language to shape what he remembered.

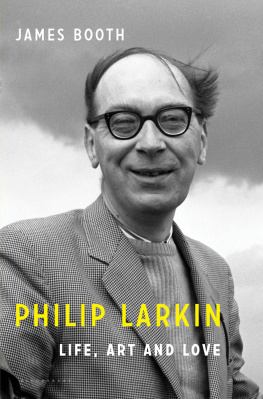

All we need to remember, when it comes to the appreciation of his mental discipline, is that his creative solitude was achieved in company, with no duty shirked. Though it is hard to imagine him looking forward to a meeting of the library car-park-space allocation committee, or whatever grim task loomed next, it is equally impossible to imagine him ducking out of it. Bohemia is a refuge, and he never stepped towards it even once, except perhaps in that short period at Oxford when he sported a cravat. The everyday might have been full of things that he found dull, but the everyday was his subject. We need to be very confident about our own everyday before we find his unexciting. In that respect, we should be cautious about joining him in his critical remarks about his owlish glasses. All the evidence and most of it is in his poetry suggests that he could hear the fizz when light hit the window. The times when he seems to complain about being less than blessed are the very times when we should remember that he was more than human, with powers of registration verging on the divine.

When Larkin seems set on being even more miserable than T. S. Eliot about the paucity of events while walking in a country lane, its important to remember that Larkin might be seeing even more than his great predecessor, and certainly seeing more than us. His powers of sensitive discrimination went all the way down to the syntax. Or not untrue and not unkind. The drama was in the shadings of the grammar. It follows that we need to pay close attention to the way he writes things down. My chief secretary on this project, the novelist Deborah Meyler, is still convinced that Larkin, in the celebrated last few lines of the poem High Windows, is painting a picture not of desolation, but of richness. (... the deep blue air, that shows/ Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.) She thinks there is hope in that. I myself think that there is no more hope in that than there is in a human body about to hit the ground after a long fall, but to convince her of her misapprehension all I can do is go on quoting Larkin at her, and I noticed long ago that her memory for his lines is even better than mine. (I only thought that I could remember every line he wrote, but it turned out that she really can.) Our struggle for supremacy will probably culminate on a slated roof, with a body falling to the gleaming street below. A matter of life and death? No: a lot more serious than that.

My other secretary, Susie Young, is present in the text more as a site-supervisor than a critic of detail, but her sane influence is still palpable throughout. Without her computer skills I would have been lost in the jungle. The influence of my elder daughter Claerwen James, who had the idea of collecting these pieces, is constantly present in the text as a bulwark against rhetorical excess. She also designed the jacket, which to my mind turns Hull into the magic city that Larkin clearly had in mind when he wrote those beautiful lines about the sunlight draining down the estuary. My wife Prue Shaw keeps up with everything I write, just in case I am showing signs too flagrant of having finally gone berserk. Luckily, however, Larkins complete works, still accumulating with the help of scholarship, are a calming influence. One wants, after all, to be as cool and clear as he was. It isnt like dealing with the kind of poet who cant talk sense to save his life. Apart from the very occasional poem that might be classified as deliberately obscure, every Larkin creation makes nothing but sense on the level of straightforward statement; and then, even more remarkably, it goes on being intelligible as it climbs into the realms of implication, until finally there you are, up above the estuary and heading down a cloudy channel towards where? Well, nowhere except everywhere.

Cambridge, 2019

Somewhere Becoming Rain

P HILIP L ARKIN , C OLLECTED P OEMS

EDITED BY A NTHONY T HWAITE

(F ABER , 1988)

At first glance, the publication in the United States of Philip Larkins Collected Poems looks like a long shot. While he lived, Larkin never crossed the Atlantic. Unlike some other British poets, he was genuinely indifferent to his American reputation. His bailiwick was England. Larkin was so English that he didnt even care much about Britain, and he rarely mentioned it. Even within England, he travelled little. He spent most of his adult life at the University of Hull, as its chief librarian. A trip to London was an event. When he was there, he resolutely declined to promote his reputation. He guarded it but would permit no hype.