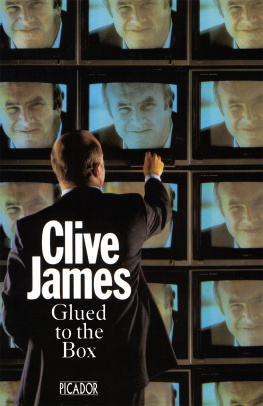

CLIVE JAMESInjury Time PICADOR

To the nurses, doctors and staff ofAddenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, England:with all my thanks for these unexpected recent years.simplex munditiis Plain in thy neatness.

Horace An author is not to write all he can, but only all he ought.

DrydenForeword When I locked up the final text for my previous volume of short poems,

Sentenced to Life, I thought, rather grandly, that there would be no time left except perhaps for a long poem that might gain in poignancy by being left unfinished. I should have known better than to flirt with the metallic music of downed tools. Before my avowedly last collection was even in proof, new short poems had begun to arrive, and after a year or so it was already evident that they might add up to a book, once I solved the problem of how to write about, say, the death of Ayrton Senna. (Surely an appropriate obsequy would need a thousand-horsepower sound-track.) In my experience, its never a book before certain key themes have been touched on, but once they are, it always is, or anyway its going to be.

It helps, of course, to have a publisher who thinks the same; and on that point Don Paterson at Picador was once again the ideal mentor. For this collection, I have kept the rule of providing notes at the end of the volume, but only if they help to explain factual points that might be obscure. If the note explained the poem itself, the poem would be incomplete. In my later stages I have got increasingly keen on that precept. Explaining itself is what a poem does. Helping me to be certain that any new project really did have something intelligible to say for itself, David Free, Stephen Edgar, Tom Stoppard, my wife Prue Shaw and my elder daughter Claerwen James saw nearly all these poems in their early stages, and often I would also run them past Ian McEwan and Martin Amis.

Though not all of these busy people thought everything I had written was marvellous, if any of them showed doubts it was always enough to make me think twice. But the day has not yet quite arrived when circulation by e-mail will count as tending an audience. Print still rules, and finally the editors of the periodicals will have to see and judge what the author fancies to be a finished product. Once again I must especially thank Alan Jenkins of the TLS, Dan Johnson of Standpoint, Paul Muldoon of the New Yorker, Tom Gatti of the New Statesman, Sam Leith of the Spectator and Les Murray of Quadrant, while welcoming a new and generous grandee to my range of principal editorial mentors: Sandy McClatchy of the Yale Review. I should also thank the Kenyon Review, one of whose operatives has only just now written to discuss a printing schedule for a couple of poems that I cant remember having sent. I go to sleep and dream of editorial ninjas breaking into my study and microfilming the MS of the unfinished epic in my bottom drawer.

Remembering how wrong I turned out to be when I thought the poems in Sentenced to Life would be my last, I should say at this point that I had to think twice before giving this book a title suggesting that the game might soon be over. As it happens, I am writing this introductory note on the morning after an operation at Addenbrookes in which items of machinery some of them, in my imagination, as big as the USS Nimitz had been sent sailing up my interior in search of organic damage. I would have liked to be awake, in order to pick up the running commentary of my lavish range of nurses and surgeons. Alas, the relaxing agent they had given me relaxed me all the way to sleep, so the only interesting dialogue I heard was from the actors in Fantastic Voyage, which, by a trick of senescent memory, had been running in my waking brain for days beforehand, and was now running, even more vividly, in the depths of my slumber. From dreams of Raquel Welch navigating between the platelets I awoke to be told that I could once again safely have breakfast. Or perhaps even safely begin writing something new.

And indeed even now, a full six years into the trajectory of my dying fall, I do still have plans for other books, including a funeral oratorio which might celebrate at some length the very fact that my confidently forecast imminent demise turned out to be not as imminent as all that. There could also be a clinching volume of memoirs, its credibility endorsed by the bark of a Luger from my study late at night. But I can be fairly sure that I am by now more or less done with the short lyrics. They take more concentration, and therefore more energy, than any other form of writing. I used always to keep the rule that if a poem started forming in my head then I should stick with it until it was finished. Here in my hideout in the Cambridge fens, in the middle of a dreary winter, with the prospect of further medical intervention retreating only to loom again, that rule begins to look too expensive.

I can still imagine myself, however, feeling compelled to break it. Finally a poem can demand to be read only because it demanded to be written, and it is notable that the dying Hamlet is still balancing his phrases even when young Fortinbras has arrived outside in the lobby. At one stage I thought of calling this little volume The Rest Is Silence, but that would have been to give myself airs. It is quite pretentious enough to evoke the image of an exhausted footballer still plugging away with legs like lead. Cambridge, 2017Contents Return of the Kogarah Kid Inscription for a small bronze plaque at Dawes Point Here I began and here I reach the end. From here my ashes go back to the sea And take my memories of every friend And love, and anything still dear to me, Down to the darkness out of which the sun Will rise again, this splendour never less: Fated to be, when all is said, and done, For others to recall and curse or bless The way that time runs out but still comes in, The new tide always ready to begin.

Do the gulls cry in triumph, or distress? In neither, for they cry because they must, Not knowing this is glory, unaware Their time will come to leave it. It is just That we, who learned to breathe the brilliant air And first were told that we were made of dust Here in this city, yet went out across The globe to find fame, should return one day To trade our gains against a certain loss And sink from sight where once we sailed away. Anchorage International In those days Russia was still closed. My flight Would cross the Pole and land at Anchorage To refuel. Many times, by day or night, I watched them shine or blink, that pilgrimage Of planes descending from the stratosphere Down some steep trail. As if Id come to stay, I lived in that lounge, neither there nor here: The still point of transition.

I would pay For drinks with cash, it was so long ago But now, again, it is a place I know. Ive changed a lot, but these seats look the same, Except there are so few of us who wait. Its like a party but nobody came. There is no voice that calls us to the gate, For no procession interrupts the sky. It seems that this time I will not move on. I have arrived.

With nowhere left to fly, I need not leave: I have already gone. Theres almost nothing left to think about Except the swirl of snow as I look out. Here in this neutral zone at last we learn That all our travelling must come to rest In stillness: no way forward, no return. We once thought to keep moving might be best Until we reached the end, but it was there From the beginning. Darkness gave the dawn Its inward depth. The lights in the night air That came down slowly were us, being born Alive.