May Week Was In June

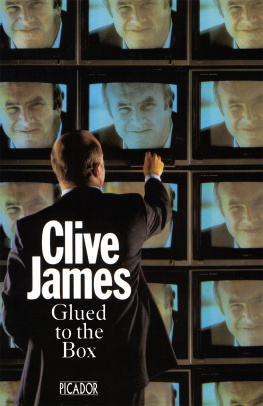

CLIVE JAMES is the author of more than thirty books. As well as essays and novels, he has published collections of literary and television criticism, travel writing and verse, plus four volumes of autobiography, Unreliable Memoirs, Falling Towards England, May Week Was In June and North Face of Soho. As a television performer he has appeared regularly for both the BBC and ITV, most notably as writer and presenter of the Postcard series of travel documentaries. He helped to found the independent television company Watchmaker, and the Internet enterprise Welcome Stranger, one of whose offshoots is a multimedia personal website, www.clivejames.com. In 1992 he was made a Member of the Order of Australia, and in 2003 he was awarded the Philip Hodgins memorial medal for literature.

ALSO BY CLIVE JAMES

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Unreliable Memoirs

Falling Towards England

North Face of Soho

FICTION

Brilliant Creatures

The Remake

Brrm! Brrm!

The Silver Castle

VERSE

Peregrine Prykkes Pilgrimage Through the London Literary World

Other Passports: Poems 1958-1985

The Book of My Enemy: Collected Verse 1958-2003

Angels Over Elsinore: Collected Verse 2003-2008

CRITICISM

The Metropolitan Critic (new edition, 1994)

Visions Before Midnight

The Crystal Bucket

First Reactions (US)

From the Land of Shadows

Glued to the Box

Snakecharmers in Texas

The Dreaming Swimmer

Fame in the Twentieth Century

On Television

Even As We Speak

Reliable Essays

As of This Writing (US)

The Meaning of Recognition

Cultural Amnesia

TRAVEL

Flying Visits

CLIVE JAMES

May Week Was In June

PICADOR

First published 1990 by Jonathan Cape Ltd

First published in paperback 1991 by Picador

This electronic edition published 2008 by Picador

an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-47435-1 in Adobe Reader format

ISBN 978-0-330-47434-4 in Adobe Digital Editions format

ISBN 978-0-330-47436-8 in Mobipocket format

Copyright Clive James 1990

The right of Clive James to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.picador.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

in memoriam

Mark Boxer and Tom Weiskel

and to

Gabriella Rosselli del Turco

where she lies sleeping

I realise very well that the reader has no great need to know all this; but I need to tell him.

Rousseau, Les Confessions

I wear a suit of armour made of nothing but my mistakes.

Pierre Reverdy, quoted by Ernst Jnger in Das zweite Pariser Tagebuch, 21 February 1943

Ive never made any secret of the fact that Im basically on my way to Australia.

Support Your Local Sheriff

Contents

Preface

Somebody once said that a trilogy ought ideally to consist of two volumes. Unfortunately he never said anything else, so his name is forgotten. When I set out to write Falling Towards England, the second volume of my unreliable memoirs, I honestly meant it to be the end of the enterprise. Gradually it became clear, however, that my entry into the University of Cambridge marked the beginning of a further episode, whose events, while less than awe-inspiring on the scale of cosmology, would suffer distortion if compressed into a few chapters. I could have made more room at the back of the book by cutting the front, but it was already cut. The nuances, after all, were everything. It would not have been enough to say that I was a failure in London. One had to convey the way failure felt: how the clothes slept in to keep one warm looked wrong next day, how a letter of rejection could be distinguished from a letter of acceptance before it was opened, how one drank to quell ones nagging conscience about having borrowed the money with which to drink. In the next generation, young people needed a heroin habit to live like that. I managed it through sheer talent. Cambridge was my way out, if not up.

Once again, though, the raw story would not have been enough. God, said Mies van der Rohe, is in the details. In Cambridge, I began to find my way, but simply to say so would have been to muff the point, because I found my way by getting more lost than ever. It was just that this time, by a bigger than usual dose of my usual extraordinary luck, I was given the chance to become confused in a fruitful, or potentially fruitful, manner. In London, entirely through my own bad management, I had been hunted from pillar to post. In Cambridge I could develop my propensities, such as they were, to the fullest extent possible, and all at once. The result was chaos. Fortunately there is a natural law, whose mathematical basis I dont pretend to understand, which says that chaos isnt always just random. It can have patterns in it. The story in this volume while being, as before, no more faithful to the facts than the ego finds convenient is as true as I can make it to the pattern which emerged when my half-formed personality was put back into the scrambler. I wont dignify the process with the name of self-discovery. The self scarcely altered. It might even have become more conscious of itself than ever. But the panic was over. I was still broke, but I had landed in the lap of the only kind of luxury I have ever cared about a wealth of opportunity. Where once every move had been forced, now there was nothing but choice. For too long the Flash of Lightning had not been free to deploy his cape or put on the mask with the stretched elastic knotted at the back to keep it fitting tightly under the strain of his amazing acceleration. Now once again he was off and running in six different directions.

Cambridge was my personal playground. It would be useless to pretend otherwise. I would be surprised if nostalgia for those easy years did not drip from the following pages like sweat. The place hasnt changed much since. The old Footlights clubroom, together with the whole rat-infested district of which it was the hub, was bulldozed to make room for the Lion Yard development, enraging some but probably saving the city from another outbreak of bubonic plague. The buses have changed colour, there has been a massacre of elms, the old Eagle is ominously surrounded by scaffolding, the Pakistani restaurant on the ground floor of the Friars House has become a souvenir shop, and fancy goods are now sold in the back room of the Whim where I once sat by the hour writing in my journal. As always, committees of dons do more than the worst developers to inflict horrible buildings on their beautiful city. Yet Cambridge like Florence, the other main location of this epic stays what it was. My life didnt. In Cambridge, in the Sixties, my course was altered and fixed, for good or ill. For this reason, though I still spend a good deal of time there, the place is always in the past to me, as epoch-making as my first pair of long pants, and almost as glamorous. The spires, the lawns, the spring alliance of jonquils and daffodils: I hardened my heart against these things, and they all went to my head. Byron kept a low profile in Cambridge, confining himself to booze, broads and leading a live bear around on a string. I was less inclined to hide my light under a bushel. The days of our youth are the days of our glory. He said it, and I believed it.