The Blaze of Obscurity

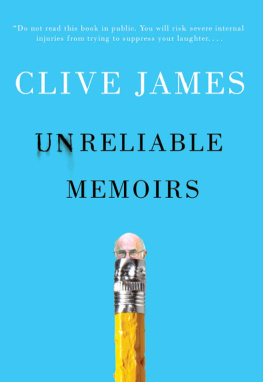

ALSO BY CLIVE JAMES

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Unreliable Memoirs

Falling Towards England

May Week Was In June

Always Unreliable

North Face of Soho

FICTION

Brilliant Creatures

The Remake

Brrm! Brrm!

The Silver Castle

VERSE

Peregrine Prykkes Pilgrimage Through the London Literary World

Other Passports: Poems 19581985

The Book of My Enemy: Collected Verse 19582003

Angels Over Elsinore: Collected Verse 20032008

Opal Sunset: Selected Poems 19582008

CRITICISM

The Metropolitan Critic (new edition, 1994)

Visions Before Midnight

The Crystal Bucket

First Reactions (US)

From the Land of Shadows

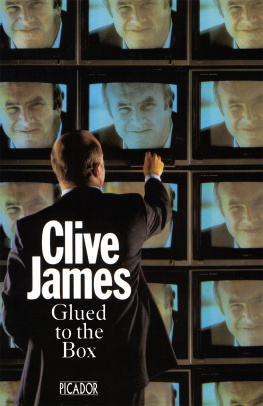

Glued to the Box

Snakecharmers in Texas

The Dreaming Swimmer

Fame in the Twentieth Century

On Television

Even As We Speak

Reliable Essays

As of This Writing (US)

The Meaning of Recognition

Cultural Amnesia

TRAVEL

Flying Visits

CLIVE JAMES

The Blaze of Obscurity

PICADOR

First published 2009 by Picador

This electronic edition published 2009 by Picador

an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Rd, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-51526-9 in Adobe Reader format

ISBN 978-0-330-51525-2 in Adobe Digital Editions format

ISBN 978-0-330-51527-6 in Mobipocket format

Copyright Clive James 2009

The right of Clive James to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.picador.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

To the memory of

Richard Drewett

All my clever dealings, he said to himself, have not made me happy. I remain a broken, restless man.

Stefan Zweig, Ungeduld des Herzens

Fool, of thyself speak well.

Richard II, V, 5

Contents

Introduction

With this fifth volume of my memoirs I begin the story of what happened to me when I left Fleet Street in 1982 and went into television as the main way of earning my bread. The effect on my literary reputation was immediate. It was thoroughly compromised, and even now, after a quarter of a century, it has only just begun to recover. After the calamitous reception of my Charles Charming show in the West End the disaster is only partly evoked in the final chapters of my previous volume, because so many of the details remain too humiliating to write down I regained the will to live by painting bicycles for my children. This creative upsurge extended itself to the construction of a novel, Brilliant Creatures. Overly decorated with flash, filigree and would-be-satirical pseudo-scholarship, the book nevertheless achieved the approval of the public. It even hung up there near the top of the bestseller list for a little while, like a parachute flare with delusions of stardom. I had to admit that the change of title might have helped. My original title had been Tactical Voting in the Eurovision Song Contest.

The book even got some favourable reviews, but the unfavourable ones were a clear indication of which way the wind would blow. My Sunday night television show about television an early instance of the medium consuming itself was pulling about ten million viewers, and my hostile literary critics drew the conclusion that to them seemed necessary. Nobody getting so famous for being so frivolous could possibly be serious. I wasnt that famous Britain, after all, was no longer the whole world but it was true that I had got into a different area of experience. It must have seemed obvious, therefore, that I had yielded up my claims to the area in which I had begun. Useless to protest that I thought all the different media were the one field. For one thing, I had not yet thought it. But I had always felt it, and indeed my Observer television column, which had been the real backbone of my career as a writer, was based on just that feeling.

Much later on, the next generation of savage young critics would embarrassingly confer on me the title of Premature Postmodernist, a title that they meant as praise, even when they bestowed it with the back of the hand. But in the early eighties and for some time forward, the savage young critics that I had to deal with were of my own generation, steadily getting less young and therefore even more critical of any of their number who showed signs of selling out. Though it was no fun to be told that I had sacrificed my gravitas on the altar of popular success, I tried not to let it bother me. The kind of television entertainment that I wanted to do could not be done without seriousness for bedrock, and I had large plans for pursuing my literary career in any spare time that I might happen to get. There was also a potential plus. Writing during my weeks off they soon turned out to be days off, and then hours I would have something extra to write about: personal experience of how the big-budget mass entertainment gets done. Going in, I had already guessed that it could never be done in solitude. Thus I would be safe from the ivory tower, an ambience to which I was suited by a reclusive, nose-picking nature, but in which my writing was always fated not to flourish. Left to myself, I would have no direct experience to report on except my own interior workings, which consisted of not much more than a couple of cog wheels, a few rusty springs and some loose screws. In broadcasting, a more richly populated territory beckoned. Really there was no choice, and not just because the work would be well rewarded. The dough was a factor, but not decisive. What mattered was the adventure.

To go on being a writer in solitude would have felt like defeat, because it would have too well served a sense of superiority that I knew to be fatal. Having dedicated my television column to the principle that mass entertainment would be a bad thing only if such a thing as a mass existed, I was now in a position to prove that I could get into mass entertainment myself, and play a full part as one of those countless individual people. They might well be viewed by political theorists as an abstract conglomerate, but they would never do any viewing themselves except one at a time. To hold their attention, you had to be one of them. It was equality; the new equality; the only real equality that there had ever been. When Tocqueville, visiting America in the early nineteenth century, said that the new democracy was imaginary, he didnt mean that it was illusory: he meant that for the first time in history the haves and the have-nots could share the same condition, even if only in their minds. Since then, the imaginary democracy had spread to the whole Western world, and in Britain it was a continuing tendency that not even Mrs Thatcher could put into reverse. How could she? She was a product of it. Though I was still trying to get all this straight in my head as a prelude to getting it down on paper, here is the story of how I made a beginning on the second stage of my long voyage, to a destination which would yield nothing more than a view of the world, though nothing less either. I had my trepidations on setting out, but I was confident enough, although even I wondered if I were wise to navigate by limelight.