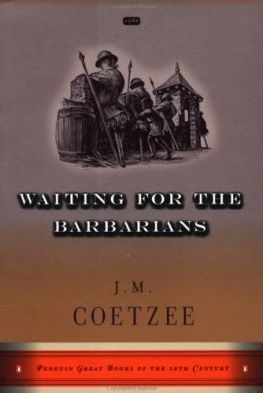

Don DeLillo - White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)

Here you can read online Don DeLillo - White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1999, publisher: Penguin (Non-Classics), genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin (Non-Classics)

- Genre:

- Year:1999

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the westcampus. In single file they eased around the orange I-beam sculpture and moved toward thedormitories. The roofs of the station wagons were loaded down with carefully secured suitcasesfull of light and heavy clothing; with boxes of blankets, boots and shoes, stationery and books,sheets, pillows, quilts; with rolled-up rugs and sleeping bags; with bicycles, skis, rucksacks,English and Western saddles, inflated rafts. As cars slowed to a crawl and stopped, studentssprang out and raced to the rear doors to begin removing the objects inside; the stereo sets,radios, personal computers; small refrigerators and table ranges; the cartons of phonographrecords and cassettes; the hairdryers and styling irons; the tennis rackets, soccer balls, hockeyand lacrosse sticks, bows and arrows; the controlled substances, the birth control pills anddevices; the jurik food still in shopping bagsonion-and-garlic chips, nacho thins, peanutcreme patties, Waffelos and Kabooms, fruit chews and toffee popcorn; the Dum-Dum pops, theMystic mints.

I've witnessed this spectacle every September for twenty-one years. It is a brilliant event,invariably. The students greet each other with comic cries and gestures of sodden collapse.Their summer has been bloated with criminal pleasures, as always. The parents stand sundazed near their automobiles, seeing images of themselves in every direction. Theconscientious suntans. The well-made faces and wry looks. They feel a sense of renewal, ofcommunal recognition. The women crisp and alert, in diet trim, knowing people's names. Theirhusbands content to measure out the time, distant but ungrudging, accomplished inparenthood, something about them suggesting massive insurance coverage. This assembly ofstation wagons, as much as anything they might do in the course of the year, more than formalliturgies or laws, tells the parents they are a collection of the like-minded and the spirituallyakin, a people, a nation.

I left my office and walked down the hill and into town. There are houses in town with turretsand two-story porches where people sit in the shade of ancient maples. There are Greek revivaland Gothic churches. There is an insane asylum with an elongated portico, ornamenteddormers and a steeply pitched roof topped by a pineapple finial. Babette and I and our childrenby previous marriages live at the end of a quiet street in what was once a wooded area withdeep ravines. There is an expressway beyond the backyard now, well below us, and at night aswe settle into our brass bed the sparse traffic washes past, a remote and steady murmuraround our sleep, as of dead souls babbling at the edge of a dream.

I am chairman of the department of Hitler studies at the College-on-the-Hill. I invented Hitlerstudies in North America in March of 1968. It was a cold bright day with intermittent winds outof the east. When I suggested to the chancellor that we might build a whole departmentaround Hitler's life and work, he was quick to see the possibilities. It was an immediate andelectrifying success. The chancellor went on to serve as adviser to Nixon, Ford and Carterbefore his death on a ski lift in Austria.

At Fourth and Elm, cars turn left for the supermarket. A policewoman crouched inside aboxlike vehicle patrols the area looking for cars parked illegally, for meter violations, lapsedinspection stickers. On telephone poles all over town there are homemade signs concerning lostdogs and cats, sometimes in the handwriting of a child.

Babette is tall and fairly ample; there is a girth and heft to her. Her hair is a fanatical blondmop, a particular tawny hue that used to be called dirty blond. If she were a petite woman, thehair would be too cute, too mischievous and contrived. Size gives her tousled aspect a certainseriousness. Ample women do not plan such things. They lack the guile for conspiracies of thebody.

"You should have been there," I said to her.

"Where?""It's the day of the station wagons.""Did I miss it again? You're supposed to remind me.""They stretched all the way down past the music library and onto the interstate. Blue, green,burgundy, brown. They gleamed in the sun like a desert caravan."

"You know I need reminding, Jack."Babette, disheveled, has the careless dignity of someone too preoccupied with seriousmatters to know or care what she looks like. Not that she is a gift-bearer of great things as theworld generally reckons them. She gathers and tends the children, teaches a course in an adulteducation program, belongs to a group of volunteers who read to the blind. Once a week shereads to an elderly man named Treadwell who lives on the edge of town. He is known as OldMan Treadwell, as if he were a landmark, a rock formation or brooding swamp. She reads tohim from the

National Enquirer, the National Examiner, the National Express, the Globe, theWorld, the Star. The old fellow demands his weekly dose of cult mysteries. Why deny him? Thepoint is that Babette, whatever she is doing, makes me feel sweetly rewarded, bound up with afull-souled woman, a lover of daylight and dense life, the miscellaneous swarming air offamilies. I watch her all the time doing things in measured sequence, skillfully, with seemingease, unlike my former wives, who had a tendency to feel estranged from the objective worlda self-absorbed and high-strung bunch, with ties to the intelligence community."It's not the station wagons I wanted to see. What are the people like? Do the women wearplaid skirts, cable-knit sweaters? Are the men in hacking jackets? What's a hacking jacket?"

"They've grown comfortable with their money," I said. "They genuinely believe they'reentitled to it. This conviction gives them a kind of rude health. They glow a little.""I have trouble imagining death at that income level," she said."Maybe there is no death as we know it. Just documents changing hands.""Not that we don't have a station wagon ourselves.""It's small, it's metallic gray, it has one whole rusted door.""Where is Wilder?" she said, routinely panic-stricken, calling out to the child, one of hers,sitting motionless on his tricycle in the backyard.Babette and I do our talking in the kitchen. The kitchen and the bedroom are the majorchambers around here, the power haunts, the sources. She and I are alike in this, that weregard the rest of the house as storage space for furniture, toys, all the unused objects ofearlier marriages and different sets of children, the gifts of lost in-laws, the hand-me-downsand rummages. Things, boxes. Why do these possessions carry such sorrowful weight? There isa darkness attached to them, a foreboding. They make me wary not of personal failure anddefeat but of something more general, something large in scope and content.She came in with Wilder and seated him on the kitchen counter. Denise and Steffie camedownstairs and we talked about the school supplies they would need. Soon it was time forlunch. We entered a period of chaos and noise. We milled about, bickered a little, droppedutensils. Finally we were all satisfied with what we'd been able to snatch from the cupboardsand refrigerator or swipe from each other and we began quietly plastering mustard ormayonnaise on our brightly colored food. The mood was one of deadly serious anticipation, areward hard-won. The table was crowded and Babette and Denise elbowed each other twice,although neither spoke. Wilder was still seated on the counter surrounded by open cartons,crumpled tinfoil, shiny bags of potato chips, bowls of pasty substances covered with plasticwrap, flip-top rings and twist ties, individually wrapped slices of orange cheese. Heinrich camein, studied the scene carefully, my only son, then walked out the back door and disappeared."This isn't the lunch I'd planned for myself," Babette said. "I was seriously thinking yogurtand wheat germ.""Where have we heard that before?" Denise said."Probably right here," Steffie said."She keeps buying that stuff.""But she never eats it," Steffie said."Because she thinks if she keeps buying it, she'll have to eat it just to get rid of it. It's likeshe's trying to trick herself.""It takes up half the kitchen.""But she throws it away before she eats it because it goes bad," Denise said. "So then shestarts the whole thing all over again.""Wherever you look," Steffie said, "there it is.""She feels guilty if she doesn't buy it, she feels guilty if she buys it and doesn't eat it, shefeels guilty when she sees it in the fridge, she feels guilty when she throws it away.""It's like she smokes but she doesn't," Steffie said.Denise was eleven, a hard-nosed kid. She led a more or less daily protest against those ofher mother's habits that struck her as wasteful or dangerous. I defended Babette. I told her Iwas the one who needed to show discipline in matters of diet. I reminded her how much I likedthe way she looked. I suggested there was an honesty inherent in bulkiness if it is just the rightamount. People trust a certain amount of bulk in others.But she was not happy with her hips and thighs, walked at a rapid clip, ran up the stadiumsteps at the neoclassical high school.She said I made virtues of her flaws because it was my nature to shelter loved ones from thetruth. Something lurked inside the truth, she said.The smoke alarm went off in the hallway upstairs, either to 'et us know the battery had justdied or because the house was on fire. We finished our lunch in silence.Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century)»

Look at similar books to White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book White Noise (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.