The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Chapter 1.

: 12 Angry Men

: Panic in the Streets

: My Darling Clementine

: High Noon

Chapter 2.

: Strategic Air Command

: Twelve OClock High and Flying Leathernecks

: From Here to Eternity

: The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell

: Attack!

Chapter 3.

Them! and The Thing

: Invasion of the Body Snatchers

: The Day the Earth Stood Still and It Came from Outer Space

Chapter 4.

: On the Waterfront , Underworld USA, The Big Heat , and Force of Evil

: Rebel Without a Cause , Blackboard Jungle, I Was a Teenage Werewolf , and The Space Children

Broken Arrow , The Searchers , and Apache

Chapter 5.

: Red River

: Giant

: Mildred Pierce

: Executive Suite

: The Fountainhead

: All That Heaven Allows

This book is dedicated to my parents,

Elliott and Sylvia,

and to Betsy, with love.

Acknowledgments

The roots of this book lie, of course, in the fifties, and I would like to thank, first off, my childhood neighbors Tom and Lillian Brandon, who laid the foundation for my affection for movies by exposing an impressionable boy to Charlie Chaplin films at a time when showing or watching them was considered almost a subversive act. Since then, I have benefitted over the years from the stimulating conversation with my friends Leo Braudy, Al LaValley, Jerry Peary, Bill Rothman, Kaja and Michael Silverman, and Paul Warshow, as well as my colleagues at Cineaste, Jump Cut, Seven Days, and American Film. I am indebted as well to Ray Durgnat, Barbara Ehrenreich, Al LaValley, Bill Rothman, and Michael Wood for scrutinizing the manuscript. Chick Callenbach encouraged me when I first began writing about film by publishing two essays in Film Quarterly that became the kernel of this book. I would also like to thank Andre Schiffrin, Tom Engelhardt, and Helena Franklin at Pantheon Books, as well as Barbara Humphrys and Emily Sieger at the Motion Picture Division of the Library of Congress; Eric Breitbart, and Martha Vaughan at American Film, for research help; Mary Corliss, who presides over the still collection, and Charles Silver, who presides over the script collection, at the Museum of Modern Art; the folks at the library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Carlos Clarens and Howard Mandlebaum for picture research; George Stevens, Jr., for permission to use stills from Giant; and Universal Pictures, Columbia, MGM/UA, RKO, Paramount, Warner Brothers, Twentieth Century-Fox, and American International (Orion) for so generously providing other stills.

I owe an incalculable debt of gratitude to my editor at Pantheon, Sara Bershtel. Saras sure sense of organization helped shape a book difficult to structure; her unerring eye for contradictions saved me from embarrassment on occasions too numerous to mention; and her infectious enthusiasm kept it going when it was trapped in conceptual and emotional dead ends. Her refusal to settle for second best, in either word or thought, is at least as responsible as I am for whatever of merit this book contains.

And finally, I would like to thank Elizabeth Hess, for whom my constant refrain, Gotta work, gotta work, became the only music for too many years.

Foreword: Happy Days

Our fat fifties cars, John Updike wrote in Museums and Women, how we loved them, revved them: no thought of pollution. The cars were the least of it. The American fifties were the age of guiltlessness, Updike said, they represented the romance of consumption at its height. There was nuclear disaster to worry about, and the Cold War, but these were distant shadows, and in the short run nothing could take the brightness out of President Eisenhowers grin or the sheen off the long suburban lawn.

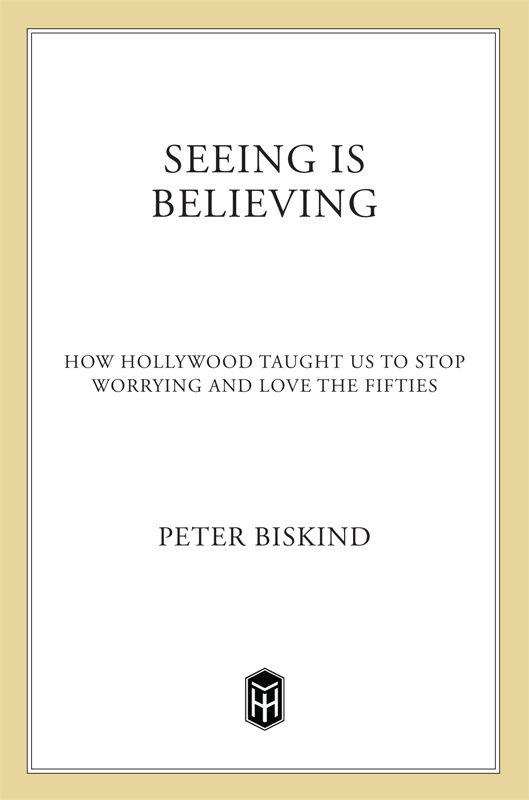

This was (and to some extent still is) the official story of the fifties, the way they have been packaged for us. Those who wish to darken the picture will murmur something about Senator Joseph McCarthy and the witch-hunts; otherwise it just seems, as Peter Biskind says, a simpler, happier time. Its easy enough to refute this story, except that one scarcely knows where to begin. Whats not so easy is to see quite what the story means. The deep argument of Biskinds mercilessly intelligent and funny book is that all this blandness is not just an error or loss of memory, a superficial interpretation of history or culture, or a product of simplifying nostalgia. It is the times own attempt to invent itself, a contemporary cover-up. The fifties is what the fifties were trying to be, and this book documents in great detail the role movies played in that attempt. When Biskind says the movies speak our language, and we learn to speak theirs, he means this language sounds natural but is actually a complicated cultural achievement.

The dominant fiction of the fifties was consensus, and Biskind shows us how the fiction works in films. The whole realm of what he calls conflict and contradiction has to be cast as a battle of unreasonable extremes against an eminently reasonable middle, often represented by technocrats, people who know how the world works. Science fiction films are full of aliens but more worried about the destruction of community than about the destruction of the earth. Social control, the conservatives nightmare, is the centrists dream. Even in war movies, Biskind suggests, the real enemy is extremism rather than Germany, Japan, or North Korea. When Arthur Schlesinger Jr., reaching for what Biskind calls a dog-eared volume of Yeats, says the center cannot hold, he may be saying that the shared moderate society of the fifties is giving way to the divided and radicalized society of the sixties. But what he ought to be saying, the films suggest, is that the old fiction wont work anymore, that the contradictions magically held at bay for a decade or more have come out into the open. The center never did hold; but it managed for a while to look as if it did. The movies didnt make this happen, but they helped to make a particular set of values seem universal, and to make a partial account seem like the whole story.

Of course the consensus, even within the movies, had its dissidents, critics on the left and the right who didnt believe in the system at all; but more often than not the system found room for them, or they turned out to be in some kind of dialogue with the system after all. The key films here, brilliantly discussed, are 12 Angry Men, On the Waterfront, and Blackboard Jungle, although Biskind has a prodigious knowledge of other movies of the time, and does a spectacular trawl through the genres.

The subject of 12 Angry Men, Biskind says, is consensus itself. The long-awaited jury verdict feels like an anti-climax. What is important in this film is not that the jury acquitted the defendant but that the decision was unanimous. 12 Angry Men is more interested in consensus than in justice. This is a little harshmaybe the movie is keenly interested in bothbut it certainly maps out the implied argument. Henry Fonda, initially the only juror with doubts, has not only done the right thing, he has brought everyone else around, including the rabid, sweating bigots played by Lee J. Cobb and Ed Begley. Their differences are all in the family, Biskind says.