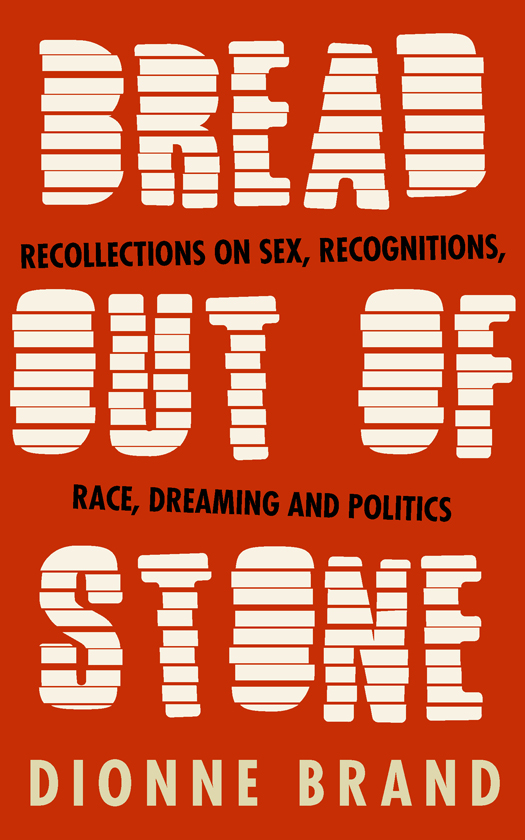

FIRST VINTAGE CANADA EDITION, 1998

Copyright 1994 by Dionne Brand

All rights reserved under International and Pan American Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by Vintage Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, in 1998. Originally published in Canada by Coach House Press in 1994. Distributed by Random House of Canada Limited.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Brand, Dionne 1953

Bread out of stone: recollections, sex, recognitions, race, dreaming, politics

Rev. ed.

ISBN: 0-676-97158-X

eBook ISBN: 978-0-345-80891-2

I. Title.

PS8553.R275A16 1998 C81454 C98-931242-9

PR9199.3.B683A16 1998

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

How It Lies, How It Lies, How It Lies!

Words and music by Sonny Burke and Paul Francis

1949 (Renewed) EDWIN H. MORRIS & COMPANY, A Division of MPL Communications, Inc. And WEBSTER MUSIC CO International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved.

Cover Design: Terri Nimmo

v3.1

For Zakiya and Faith Eileen

Contents

Just Rain, Bacolet

B ack. Here in Bacolet one night when the rain falls and falls and falls and we swing the door wide open and watch the rainy season arrive I think that I am always travelling back. When the chacalaca bird screams coarse as stones in a tin bucket, signalling rain across this valley, when lightning strafes a blue-black sky, when rain as thick as shale beats the xora to arrowed red tears, when squat Julie trees kneel to the ground with the wind and I am not afraid but laugh and laugh and laugh I know that I am travelling back. Are you sure that this is not a hurricane? Faith and Filo ask. No, I say, with certainty, its just rain. I know this, its just rain just rain, rain is like this here. You can see it running toward you. And this too, dont fight the sea and dont play with it either, that shell blowing means theres fish in the market and, yes, Id forgotten the water from young green coconuts is good for settling the stomach, you have to cut or scrape the skin off shark before you cook it, otherwise its too oily and this prickly bush, susumba, the seed is good for fever, and the bark of that tree is poison Knowing is always a mixed bag of tricks and so is travelling back.

On one side of this island is the Atlantic and on the other the Caribbean Sea, and sometimes and very often if you drive up, up the sibilances of Signal Hill to a place called patience, yes, Patience Hill, you can see both. There are few places you can go to without seeing the sea or the ocean and I know the reason. It is a comfort to look at either one. If something hard is on your mind and you are deep in it, if you lift your head you will see the sea and your trouble will become irrelevant because the sea is so much bigger than you, so much more striking and magnificent, that you will feel presumptuous.

Magnificent frigate drapes the sea sky, magnificent frigate. Bird is not enough word for this nor is it enough for the first day just on the top of the hill at Bacolet that red could draw flamboyant against such blue and hill and cloud and the front end of the car floats between them

at first I went alone, was brought, arrived, came, was carried, was there, here, the verb is such an intrusive part of speech, like travelling, suggesting all the time invasion or intention not to leave things alone, so insistent you want to have a sentence without a verb, you want to banish a verb.

Anyway, I was carried by the way theyd cut the road, fast and narrow, and with magic because always it was impossible for two cars to pass each other but it happened, and magic because one afternoon cutting through the rain forest on Parlatuvier Road to Roxborough but right in the middle of the rain forest a woman and soft in the eyes and old like water and gentle like dust and hand clasped over the hand of her granddaughter little girl appeared, walking to Roxborough. So we stopped, seeing no house nearby that she may have come from or be going to. The road was treed and bushed on all sides, epiphytes hung from the palmiste and immortelle, and we stopped to her Thank you, darling, thank you. What a sweet set of children! I going just down the road. Thank you, darling. To be called darling and child, we knew it was magic because no one, no stranger in the last twenty-four years of my life and in all of Faiths living in the city we had left, had called us child and darling. We stared, grinning at her. We settled into her darling and child just like her granddaughter settled into her lap. Magic because she had appeared on the road with her own hope, a hope that willed a rain forest to send a car with some women from North America eager for her darling, her child, or perhaps she wasnt thinking of us at all but of walking to Roxborough with her granddaughter to buy sugar or rice and her darling and child were not special but ordinary, what she would say to any stranger, anyone, only we were so starved for someone to call us a name we would recognise that we loved her instantly.

One day we are standing in a windmill no, standing in a windmill, trying to avoid the verb to meet, which is not enough for things that exist already and shadow your face like a horizon. We climbed to the top of the windmill at Courland Bay with S. The wooden banisters have been eaten away by termites. Theyve eaten the insides of the wood, ever existing, trying to avoid the verb to meet, as I, we. We learn that you cannot hold on to the banisters though the outside looks as it might have looked then. She had told us what year, some year in another century, 1650, or perhaps 1730. We climbed to the top, passing through the bedrooms the windmill now holds, the bats droppings in the abandoned rooms, then outside to the top, up the iron stairs. That is when she said that the mill had been here, a sugar mill, a plantation, and there were the old buildings, traces of them, there since then. That is when she showed us the old building, near the caretakers house, near the cow roaming on her thick chain, near the governor plum tree, tangled up in mimosa and razor grass, but not covered and not all of it there. We learn that you cannot come upon yourself so suddenly, so roughly, so matter-of-factly. You cannot simply go to a place, to visit friends, to pick mangoes on your way to the beach and count on that being all. You cannot meet yourself without being shaken, taken apart. You are not a tourist, you must understand. You must walk more carefully because you are always walking in ruins and because at the top of a windmill one afternoon on your way to the beach near Courland Bay you can tremble. At the top of a windmill one afternoon on your way to bathe in the sea when you stop off to pick some mangoes you might melt into your own eyes. I was there at the top of the windmill taken apart, crying for someone back then, for things which exist already and exist simply and still. Things you meet. I am afraid of breaking something coming down. Something separates us.

We leave the top of the windmill and the owner, who is still talking about carving it up and selling it in American dollars, and go to talk to the caretaker who feels more like home, more like people. He knows the kind of talk we need, talk about the rich and the poor, talk about why you can weep when looking at this place, talk that sounds quiet in the trembling and razor grass, as if he understands that there are spirits here, listening, and we must wait our turn to speak, or perhaps what they are saying is so unspeakable that our own voices cut back in the throat to quietness. This is where it happened and all we can do is weep when our turn comes, when we meet. Most likely that is the task of our generation: to look and to weep, to be taken hold of by them, to be used in our flesh to encounter their silence. All over there are sugar mills even older, filled with earth and grass. Now everything underfoot is something broken.