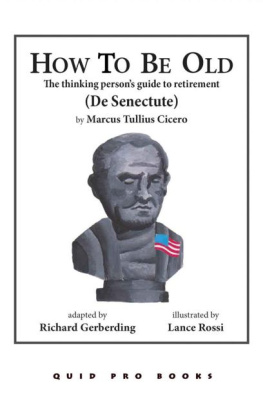

Smashwords edition. Copyright 2014 by Richard Gerberding. Illustrations and cover design 2014 by Lance Rossi. No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, or other recording, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied for public or private use other than for fair use without the written permission of the publisher. This work is a modern adaptation of the classic essay On Old Age by Marcus Tullius Cicero, with further commentary and illustrations.

Published in 2014 by Quid Pro Books, at Smashwords.

From them I have learned the important things.

Thanks ...

In the preparation of a book, gratitude is due to many people. Let me publicly and from my heart thank two groups:

Andrew Dunar, Bryan Ward-Perkins, and Heidi Colsman-Freyberger who kindly read the manuscript in its entirety and saved me from much disgrace.

David, Matilde, Mical, and Gavriel Betti-Nelken who gave me food, shelter, love, and great encouragement during its writing.

Adaptors Preface

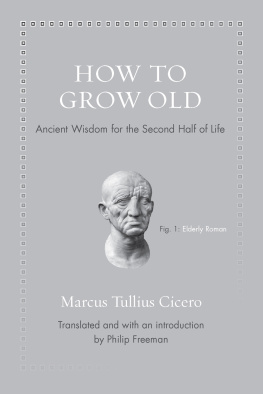

Getting old is not for sissies the mortal words of Bette Davis. What you have in your hands are the immortal words of Marcus Tullius Cicero on the same subject. Well, almost the same words; I have jacked some around a bit, deleted and added a few here and there to make him clearer to us non-Romans. Over two thousand years ago, the Roman statesman Cicero, or Old Tully as he was sometimes known in the nineteenth century, wrote a work called On Old Age . If he wrote it today, Revlon and Max Factor would buy up the rights and suppress it. But the Roman cosmetic merchants didnt, and Ciceros book has not only survived, but has been superbly edited and elegantly translated into most of our modern languages and so, of course, almost nobody reads it but academics.

About twenty-five years ago when my parents were retiring, Tullys tome on getting old was pressed into my none-too-eager hands by my Latin teacher. I read it, as most do, because I had to, but I was amazed and delighted by what I found. The book was my first brush with what I now know to be moral philosophy. This branch of philosophy is not the highly intellectual, rigorous (and often deathly dull) pursuit of the academic and professional thinker, but rather the serious consideration of the best way to live. Moral philosophy, thank goodness, is a healthy step above the self-help books, but often has the same purpose. Marcus Cicero certainly knew how to live. He came from the hind foot of nowhere to become high societys most successful lawyer, was the most imitated writer in Latin, lived in the Beverly Hills or Chevy Chase of his day, had several charming second homes in the Italian countryside, and lived a daily routine full of servants, family, students, and admirers. At one point he was the elected head of the Roman state, which meant that he governed a huge foreign empire, and he was in debt up to his Roman ears. Nothing deathly dull here. He was known for his clear head, his eloquence, his high sense of duty, and his sense of humor, which also got him into trouble. Like many eloquent people, he often didnt know when to shut up. Tribonius, one of Caesars henchmen, published a book of Ciceros jokes while Cicero was still alive.

It was probably fate and not coincidence that caused me to read Ciceros book at the same time as Mom and Dad retired, because I noticed that Tullys and middle-class Americans approaches to old age were at odds. My parents moved mountains to deny that they were in the third stage of life, whereas Cicero points out its advantages and asks us to accept it as natural and good. For my parents and their friends, there was nothing natural or good about it. Out came the tennis shorts, the hair dye, the youthful Polo shirts. They bought speed boats. Some took up running, others skiing, even weight-lifting. Adolescent words fell awkwardly from their lips, words like gang, kids, workout, whatta blast!, and oh, youre soooo tan. Their retirement activities seemed to be primarily ones of the body, not the mind. Snorkeling rather than art, architecture, or intelligent conversation seemed to represent the ideal pastime. Now some twenty-five years later as I face retirement myself, I listen in horror to my own mouth: cool, hang out, awesome, and I read about lifts, tucks, and Botox.

It aint for sissies, but I am convinced it is best lived as Tully advises, that is, accepting it as natural and exploiting its own natural advantages. Besides, your knees probably look as ridiculous as mine do below those tennis shorts.

So why should you read this version of On Old Age rather than the ones produced by professional classicists? Because here I have attempted not simply to translate the Latin (something which I did do) but to transpose and adapt his work to American surroundings. His ideas are so provocative, so wonderful, so helpful, so natural, and so reassuring that I found it a tragedy that they could be lost in translations whose purposes were linguistic accuracy rather than pertinence. I have tried to make him as relevant and as readable to modern American thinking men and women as he was to their ancient Roman counterparts. Exit all his references to obscure ancient generals and philosphers and enter Dwight Eisenhower and Irving Berlin. Cicero was not talking to those who do not think about what they do; the mindless went to gladiatorial games or to the racetrack. If Nascar is the center of your retirement, this book is not for you. But if you try to be aware of the world around you, enjoy intelligent conversation and worthwhile ideas, and want to be proud of the years you have earned, take Old Tully home with you, have a nice dinner, listen to him, and think very carefully about what he says. He will become as valued a friend of yours as he is of mine.

R. Gerberding

Bologna, Italy

June, 2014

How to Read This Book

This book is not for sissies: it contains the sort of serious thinking that has lasted for over two thousand years, but it takes mental effort to extract it. Cicero was aware of this and wrote with a style and clarity that would make the weight of his thoughts easier to bear. He did not write for philosophers but for us. When you read him, think. It is okay to lower the book, peer out over your glasses (probably bifocals like mine) and reflect on the two or three sentences you have just read. If you dont think as you read, you are likely to consider the first part of the book simply intelligent common sense and the last part, the sections about death and the immortality of the soul, as simply nicely worded piety. But they arent. Every part of this book is important. There is very little fluff in here. There are only three structural elements: (1) very few words that establish the fictitious historical setting and dialogue, (2) his ideas, and (3) specific examples from history or literature that support the ideas. Thats it. So again, it is okay to stop and ponder, and if what you read seems simplistic, it is okay to re-read it. Nobody has to know how long it took you to read a short book. He has much to say to us oldies, and one of the most valuable lessons for us is to consciously and actively engage our minds. Do mental push-ups, intellectual workouts. The intelligent reading of his book will serve very nicely as your time in the mental fitness center. But no slouching, otherwise you will miss his points.