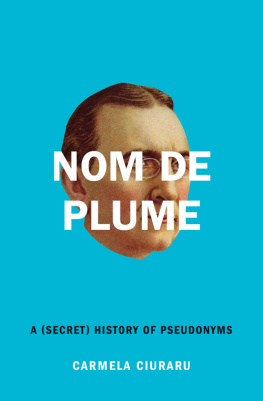

Nom de Plume

A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms

Carmela Ciuraru

For Sarah, everything

(and for Oscar)

World is crazier and more of it than we think.

Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion

A tangerine and spit the pips and feel

The drunkenness of things being various.

LOUIS MACNEICE , Snow

On whom, then, my God, am I the onlooker? How many am I? Who is me? What then is this gap between myself and me?

FERNANDO PESSOA

Must a name mean something? Alice asked doubtfully.

Of course it must, Humpty Dumpty said, with a short laugh. My name means the shape I am and a good handsome shape it is, too. With a name like yours, you might be any shape.

LEWIS CARROLL , Alices Adventures in Wonderland

The self is like a bug. Every time you smack it, it moves to another place.

PAT STEIR

Contents

Anne, Charlotte, and Emily Bront & Acton,Currer, and Ellis Bell (18161855)

Once there were fivesisters....

George Sand & Aurore Dupin (18041876)

It began with anankle-length gray military coat, matching trousers, a cravat, and awaistcoat....

George Eliot & Marian Evans (18191880)

Charles Dickens wassuspicious....

Lewis Carroll & Charles Dodgson(18321898)

A show of hands if youvenever heard of Alice in Wonderland....

Mark Twain & Samuel Clemens (18351910)

How the protean SamuelClemens became the worlds most famous literary alias will never be knownfor sure....

O. Henry & William Sydney Porter(18621910)

If you are now reading orhave recently read a short story by O. Henry, you are most likely amiddle-school student....

Fernando Pessoa & His Heteronyms(18881935)

You will never get to thebottom of Fernando Pessoa....

George Orwell & Eric Blair (19031950)

Had Eric Arthur Blair beena working-class bloke from Birmingham instead of an OldEtonian...

Isak Dinesen & Karen Blixen (18851962)

She was descended fromDanish royalty, but her childhood was filled with the traditional privilegesof an aristocratic upbringing....

Sylvia Plath & Victoria Lucas(19321963)

She was a good girl wholoved her mother....

Henry Green & Henry Yorke (19051973)

Hes the best writeryouve never heard of....

Romain Gary & mile Ajar (19141980)

He was a war hero, aPing-Pong champion, a film director, a diplomat, and an author who wrote thebest-selling French novel of the twentiethcentury....

James Tiptree, Jr. & Alice Sheldon(19151987)

On May 19, 1987, aseventy-one-year-old woman and her eighty-four-year-old husband were foundlying in bed together, hand in hand, dead of gunshotwounds....

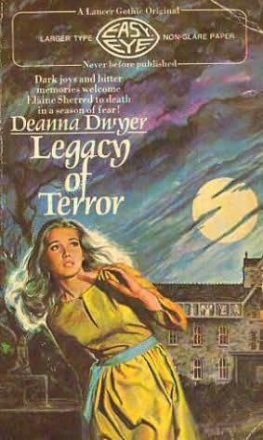

Georges Simenon & Christian Brulls et al.(19031989)

He claimed to have had sexwith ten thousand women....

Patricia Highsmith & Claire Morgan(19211995)

She was one of the mostwretched people you could ever meet, with mood shifts that swung as wildlyas the stock market....

Pauline Rage & Dominique Aury(19071998)

Not many authors can boastof having written a best-selling pornographicnovel....

At its most basic level, a pseudonym is a prank. Yet the motives that lead writers to assume an alias are infinitely complex, sometimes mysterious even to them. Names are loaded, full of pitfalls and possibilities, and can prove obstacles to writing. Virginia Woolf, who never adopted a nom de plume herself, once expressed the fundamental and maddening condition of authorship: Never to be yourself and yet alwaysthat is the problem. She was describing the predicament of the personal essayist, but identity can seem crippling to any writer. A change of name, much like a change of scenery, provides a chance to start again.

To a certain extent, all writing involves impersonationthe act of summoning an authorial I to create the speaker of a poem or the characters in a novel. For the audacious poet Walt Whitman, it was possible to explore other voices simply as himself. He embraced his multitudes. (Do I contradict myself? / Very well then, I contradict myself.) But some writers are unable to engage in such alchemy, or dont want to, without relying on an alter ego. If the authorial persona is a construct, never wholly authentic (no matter how autobiographical the material), then the pseudonymous writer takes this notion to yet another level, inventing a construct of a construct. [T]he cultivation of a pseudonym might be interpreted as not so very different from the cultivation in vivo of the narrative voice that sustains any work of words, making it unique and inimitable, wrote Joyce Carol Oates in a 1987 New York Times essay. Choosing a pseudonym by which to identify the completed product simply takes the mysterious process a step or two further, officially erasing the authors (social) identity and supplanting it with the (pseudonymous) identity. Elide your own name, and imaginative beckoning can truly begin. As the French journalist and writer Franois Nourissier once noted (in a piece entitled Faut-il crire masqu?), a nom de plume provides a space in which obstacles fall away, and ones reserve dissipates.

The merging of an author and an alter ego is an unpredictable thing. It can become a marriage, like a faithful and sturdy partnership, or it can prove a swift, intoxicating affair. A clandestine literary self can be tried on temporarily, to produce a single work, then dropped like a robe; or the guise might exist as something to be guarded at all costs. The attraction is obvious and undeniable. Entering another body (figuratively, ecstatically) is almost an erotic impulse. Historically, many writers have been lonely outsiders, which is why inhabiting another self offers an intimacy that seems otherwise unobtainable. In the absence of real-life companionship, the pseudonymous entity can serve as confidant, keeper of secrets, and protective shield.

The term alter ego is taken from Latin, meaning other I. This suggests the writer is not so much wearing a mask as becoming another person entirely. Have the two selves met? Maybe not, and its probably better that way. Sometimes theres no reason to explore how or why the other half lives. Knowing that it does is enough.

In his influential 1974 book The Inner Game of Tennis , author Timothy Gallwey applied the notion of doubleness to the tennis player, describing how each self hinders or enhances performance. With almost no technical advice, he provides a prescriptive guide to mastery. He focuses on what he describes as two arenas of engagement: Self 1 and Self 2. When his book was first published, Gallweys ideas were so radical that thousands of readers wrote to express their gratitude, saying that theyd successfully applied his principles to pursuits other than tennis, including writing.

Gallwey, who majored in English literature at Harvard University, portrays Self 1 as the talker, critic, controlling voice, and notes its persistence and inventiveness in finding opportunities to get in the way. Self 1 berates you, calls you an incorrigible failure. But the nonjudgmental Self 2 represents liberation in its purest form. As Gallwey writes, Self 2 is much more than a doer. It is capable of a range of feelings that are the most uniquely human aspect of life. These feelings can be explored in sports, the arts... and countless other activities. Self 2 is like an acorn that, when first discovered, seems quite small yet turns out to have the uncanny ability not only to become a magnificent tree but, if it has the right conditions, can generate an entire forest. In the context of authorship, the freeing of an alternate identity (Self 2) can reveal not just a forest but new worlds, boundless and transgressive, thrilling beyond ones wildest dreams.

Next page