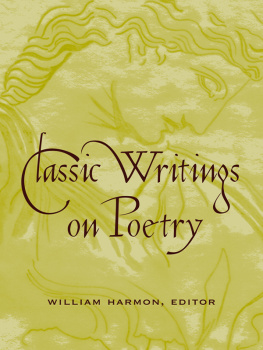

Also available

The Literary Theory Toolkit: A Compendium

of Concepts and Methods

Herman Rapaport

This edition first published 2012

2012 William Harmon

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007.

Blackwell's publishing program has been merged with Wiley's global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell .

The right of William Harmon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harmon, William, 1938

The poetry toolkit: for readers and writers / William Harmon

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9578-2 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-4051-9577-5 (pbk.)

1. PoetryAuthorship. 2. PoetryAppreciation. 3. Poetics. I. Title.

PN1059.A9.H37 2012

808.1dc23

2011037208

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Preface

Nobody knows nothing about poetry.

If you can read well enough to understand that sentence, then you have been meeting poetry in some form for some years, and such meetings will continue throughout your life. Everybody knows something about poetry, but nobody understands everything about it, and everybody can always learn more. The more you know, the more you can enjoy reading and writing poetry.

Eventually you may master such terms as antimetabole, englyn, and drottkvtt, but first you will need some rudiments. It is encouraging that, even without rudiments, you can still get genuine pleasure out of reading and writing poetry, but, if you will be honest with yourself, you may soon recognize that some frustrations, which come when reading and especially when trying to write, can be eased by learning more about the arts and techniques of poetry.

This book aims to exploit what people already know, in some sense, in order to increase their understanding and appreciation. This procedure of moving from the known to the unknown may not account for such things as whim, luck, guesswork, serendipity, and accident, but it does provide a reasonable basis for what we do.

In any process of learning, you will probably reach a point of suddenly exclaiming, Oh! I get it! A toolkit can hope only to furnish the materials for facilitating such leaps of intuition and illumination. Most readers begin with a vague unexplained liking for something; the liking may impel them to learn more and to try harder to explain and understand.

The first six chapters of this book follow a systematic division of the elements of poetry, considered in a certain order:

overall design (plot of action, story of some sort), along with rhetorical attitude;

character (the persons or other agents involved in an action);

thought, feeling, state of mind (the background and motivation of character);

diction vocabulary and syntax (the verbal expression of thought and feeling);

sound (the pronunciation of words);

graphic effects (the appearance of words on a page).

Those are not the only elements, and that is not the only order, but the approach remains sound, rational, and time-tested. The first three elements apply to almost any literary work, prose and poetry alike; the last three have been associated mostly with poetry to one degree or another. The seventh chapter takes up various ways in which one poem can interact with another, along with a measure of entertainment.

Some have begun writing by producing the sixth element first, that is, with a poem- looking object, which, as with many poems, has a more or less justified left margin and an unjustified right margin. But you will probably not know what the poem looks like until you know what it sounds like. Some, therefore, produce a poem- sounding object, with words that rhyme, for example, but they will not know what sounds to combine until they know what words they ought to use. They will not know what words to use until they know what thoughts and feelings are to be expressed, and they will not know much of that, in turn, until they know what characters are involved; and the characters in turn are a function of the overall story. Accordingly, it is best to begin with the governing elements.

Having encountered terms associated with poetry in one way or another anapest, tragedy, poetic justice, irony, overstatement, braggart, stanza, subordinate clause, vulgarism, rhyme, metaphor students might not have thought consciously about how certain kinds of characters belong in certain kinds of stories, or how certain levels of vocabulary or textures of syntax belong with certain kinds of character, or how any of those things relate to rhythm and meter. And much about the whole process will necessarily remain forever irrational, mysterious, and controversial. (That is part of the fun.) But at any rate the matters can be laid out in an orderly fashion that will, if nothing else, at least permit analysis and debate.

Learning the rudiments of reading often leads to a desire to write for oneself. Someone with hardly a clue may not know whether to say autumn or fall in a given situation, except that it's just the word I wanted to express myself spontaneously; and, while that is not a strong argument, neither is it a wrong argument; sometimes it is all we can come up with. Every day we choose from taxicab, taxi, or cab, phone or telephone, newspaper or paper, for some reason or another, and we do not always know why. On the matter of taxi, one recent writer, the actor Peter Bull, went so far as to use taximetercabriolet, a choice that can be explained historically as the primitive ancestor of taxicab but maybe not vigorously defended, except as a humorous affectation. Perhaps taxicab preserves the ghost or tissue memory of its earliest form.

Writers all began as readers, and, unless one is an exceptionally spontaneous genius, a writer can benefit by reason and reflection as well as whimsy and a sense of fun.

Next page