Zinn - The Zinn reader

Here you can read online Zinn - The Zinn reader full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Seven Stories Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Zinn reader: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Zinn reader" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Zinn: author's other books

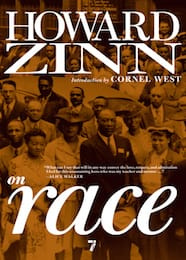

Who wrote The Zinn reader? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Zinn reader — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Zinn reader" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Noah, and his generation.

Acknowledgments

I must first thank my editor and publisher, Dan Simon of Seven Stories Press, not just for initiating this project, but for carrying it through all the way with extraordinary intelligence and energy. He is an ideal editor, clear in his vision of what a book should be, firm in pursuing that vision, and still sensitive to the needs of the writeraltogether a pleasure to work with.

My wife Roslyn, as always, encouraged me to do what had to be done, providing wise counsel again and again.

Thanks also to HarperCollins for permission to use material from my book Declarations of Independence, to Beacon Press for permission to use material from my book You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train, to the University of Illinois Press for permission to use material from my book The Politics of History.

Introduction

This seems to me a big book to swallow, and I blame it on the fact that in 1978, when I was teaching in Paris, I looked up the son of friends back in the States, a young man of college age. He was working in a tiny restaurant in the Latin Quarterindeed with only one tableLe Petit Vatel. This was the start of a friendship with Dan Simon, who went on to become the ingenious editor and publisher of the small, independent, much-respected Seven Stories Press, and who proposed the idea of a Zinn Reader.

I delayed my response for two years, to give the appearance of modesty, and then agreed. I wanted to think of it as a generous actgiving all those who know my biggest-selling book (A People's History of the United States) a chance to sample my other work: books out of print, books still in print, essays, articles, pamphlets, lectures, reviews, newspaper columns, written over the past thirty-five years or so, and often not easy to find. An opportunity, or a punishment? Only the reader can decide.

My first published writings came out of my seven years in the South, teaching at Spelman College, a college for black women in Atlanta, Georgia. I was finishing my Ph.D. in history at Columbia University, with the indispensable help of the GI Bill, after serving as a bombardier with the Eighth Air Force in World War II.

My years at Spelman were 1956 to 1963, and I became involved, with my students, in the Southern movement against racial segregation. My very first published article, in Harper's Magazine in 1959 ("A Fate Worse Than Integration"), became the basis for a larger essay "The Southern Mystique," which appeared in The American Scholar.

I was invited to become a member of the executive board (as an "adult adviser") of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which had come out of the sit-ins and was, I think it is fair to say, the leading edge of the Southern civil rights movement. In the next several years I became an observer-participant in demonstrations in Atlanta; in Albany, Georgia; Selma, Alabama; and Hattiesburg, Mississippi. I was now writing for The Nation, The New Republic, The Crisis, and other publications.

The historian Martin Duberman, whose documentary play, In White America, I had greatly admired, asked me to write an essay comparing the Civil War-era abolitionists with the activists of the Sixties. It appeared in a volume he edited called The Anti-Slavery Vanguard, and I called it "Abolitionists, Freedom Riders, and the Tactics of Agitation." It was an approach I was going to use again and againto find wisdom and inspiration from the past for movements seeking social justice in our time.

There was never, for me as teacher and writer, an obsession with "objectivity," which I considered neither possible nor desirable. I understood early that what is presented as "history" or as "news" is inevitably a selection out of an infinite amount of information, and that what is selected depends on what the selector thinks is important.

Those who talk from high perches about the sanctity of "facts" are parroting Charles Dickens' stiff-backed pedant in Hard Times, Mr. Gradgrind, who insisted his students give him "facts, facts, nothing but facts." But behind any presented fact, I had come to believe, is a judgment the judgment that this fact is important to put forward (and, by implication, other facts may be ignored). And any such judgment reflects the beliefs, the values of the historian, however he or she pretends to "objectivity."

I was relieved when I decided that keeping one's judgments out of historical narrative was impossible, because I had already determined that I would never do that. I had grown up amidst poverty, had been in a war, had witnessed the ugliness of race hatred, and I was not going to pretend to neutrality.

As I told my students at the start of my courses, "You can't be neutral on a moving train." That is, the world is already moving in certain directionsmany of them horrifying. Children are going hungry, people are dying in wars. To be neutral in such a situation is to collaborate with what is going on. The word "collaborator" had a deadly meaning in the Nazi era. It should have that meaning still.

Therefore, I doubt you will find in the following pages any hint of "neutrality."

The GI Bill paid my way all through undergraduate and graduate school. While my wife, Roslyn, worked, and our two kids were in nursery school, we lived in a low-income housing project on the Lower East Side. I attended classes during the day and worked the four to midnight shift loading trucks at a Manhattan warehouse. It is hardly surprising that I was to have a persistent interest, as a historian, in the issue of economic justice.

For my doctoral thesis at Columbia University I chose as my subject Fiorello LaGuardia. He was known best as the feisty, rambunctious mayor of New York in the New Deal era, but before that, in the Twenties, he was in Congress, representing a district of poor people in East Harlem.

As I began reading through his papers, left to the Municipal Archives in New York by his widow, he spoke to my young radicalism. He was on his feet in the House of Representatives perhaps more often than any other member, demanding to be heard above the din of the Jazz Age, crying out to the nation about the reality of suffering underneath the spurious "prosperity" of the Twenties.

My thesis, "Conscience of the Jazz Age: LaGuardia in Congress," won a prize from the American Historical Association, which sponsored its publication by Cornell University Press. Out of that came an essay published in my book The Politics of History. It was a glimpse of LaGuardia at work against the hypocrisy of "a booming economy" which concealed distress. We see that today in the exultation accompanying every upward leap in the Dow Jones average, even while a quarter of the nation's children grow up in poverty.

Reading on my own, I became fascinated by the history of labor struggles in the United States, something that was absent in my courses in American history. Reaching back into that history (often disheartening, often inspiring), I began to look closely into the Colorado coal strike of 1913-14, and my essay "The Ludlow Massacre" comes out of that.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Zinn reader»

Look at similar books to The Zinn reader. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Zinn reader and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.