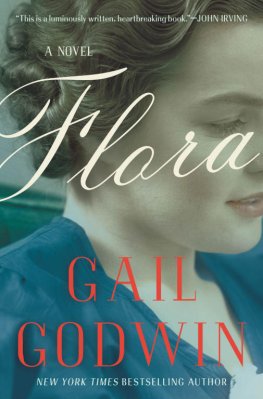

Fall

1

Borrowed Houses

I T WAS AFTER HER FATHERS DEATH Flora returned to Darwin. Returningwith all the criminal associationsto the scene of her growing up had been a task shed put off, rebuffing her fathers invitations. You dont go home much, do you? friends would ask. Homethat fuzzy image of innocence, that haven of recognition. The place you long for when adrift.

Her fathers voice in her minds ear paused her: So all I had to do, Flo, to get you to Darwin was die? But it did not stop her. She caught a taxi to the bus station, and took the bus to its terminus, a desolate former mill town thirty minutes from Darwin, and then she loaded herself and her body bag of a suitcase into a country cabmore properly called a car, a crumby minivan, with nothing marking it as professional in any waynow bringing her to her fathers house.

She did not sublet her apartment in the city; there wasnt time, and the thought of someone else sleeping in her bed and filling her closets made her anxiousan only child, shed never liked to share. She knew what people did in other peoples houses, and did not want it done to her. And who knew how long shed be gone. But she had taken the time to pack all the things she liked best, leaving the B garments behind. She packed her three favorite pairs of jeans of varying degrees of tightness and wear, a pair of black corduroys, two A-line skirts, one high-slitted denim pencil skirt, and a black silk dress shed bought several years back upon receiving her first reasonable paycheck, imagining a life of cocktail parties and cigarette holders, and worn once. She packed socks and tights, three delicate wool cardigans, one milky white cable-knit cashmere turtleneck, five long-sleeved cotton shirts of assorted saturated colors, clogs, her turquoise old-lady slippers, sweatpants and two concert T-shirts shed had since high school, boots (one pair heeled, one flat), her six sexy pairs of underwear and her four unsexy, old, comforting pairs of underwear, and various scarves and hats. She packed a short, beaded 1920s-style flapper dressa prime example of her favorite category of clothing: inappropriate for every occasion (and thus equally appropriate for all occasions)and a pair of pewter-colored four-inch heels of the same category. She packed soap, shampoo, and other ablutions (as if she were traveling to the tundra, where such items could not be procured, and not to New England, where they could, but then they might be inferior), and, in the midst of the vanities, she buried the folder of her fathers poems. If I lose this bag, she thought, forcing the zipper across its length, Ill be very sad.

Darwin was three hours from everywhere: Flora was unready to arrive. It was dusk, and quiet, her country cab passing the odd station wagon loping home. Darwinthe one place in America SUVs had not yet colonized. Perhaps they were against the law. Here the indigenous station wagon still reigned supreme over his niche. Here talk of carbon footprint was as routine as talk of gas prices elsewhere. The town of Darwin knew unhappinessthe Darwinians self-satisfied but not content. Thick with academics and their broodsidlers, ruminators, moseyers. Thoughtful people, thinking thoughts. No one hurrying down the few placid streets. Hadnt the Darwinians anything urgent to attend to? Yes, they had not. Poets and the world romanticize being idlethe boon of free time praised, guarded, enviedbut anyone who has idled for a living knows the damaging effects it can have on the moods.

The minivan was overheated, stifling. The window wouldnt budge. Floras hair itched with sweat. She was being cooked alive. She took off her hat, uncoiled her scarf, unbuttoned her coat. She was a child. Her clothes, hidden all day beneath layerswhy did one prefer to keep ones coat on in public transit?announced a complete regression. The faded black sweatshirt, the army green pants with the patched knees and safety-pinned waist, the red sneakers that she dearly loved. Not a day over sixteen, her father had said of her face. At what age did the compliment of youth expire?

The driver tried talk: What brings you to Darwin? He had the overeager voice of one stranger requiring something of another.

You know, Flora said. Family. But once shed said the words, they sounded unkind. The mans face ravaged, ungroomed. It was possible he did not know much of family. A woman in his life would have suggested a haircut weeks ago.

Still, the unkindness hanging in the close air was preferable to chat. She glanced at her cell phone to check the time. It was now rejecting text messagesan apt technological gestureits tiny brain at capacity, and Flora thought with pleasure of her friends agonizing over compassionate abbreviated condolences, only to have them bounce right back to their machines as though repellent.

Her fathers house sat at the edge of the town proper, a ten-minute walk from the Darwin College campus. An old farmhouse, it had recently been repainted an excellent taupe. When, exactly? Even through the fouled window of the car, it had never looked prettier, or she hadnt remembered it that way. A pretty house, certainly, but shed thought of it as resigned and downtrodden in that way peculiar to academics and their surroundings. But her father, it seemed, had even taken up gardening, or else hired someone to work on the historically neglected flower beds circling the house like a moat, the odd stem standing its ground as though it didnt know it was November. The house was a relic from a happier time. The house was showing off. The house was oblivious; it hadnt been informed of recent developments.

She overtipped the driver as an apology for her curtness and he hauled her morbid duffel to the doornewly painted, slate blue. Flora hesitated, as at the door of an acquaintance, where she might not be welcome, or know anyone inside. The house of a sixty-eight-year-old retiree bachelor, a reclusive reader, an academic with no more classes or committees to order his life around. Would it be pathologically unkempt, like the foul apartments of boys shed dated post-college, the disordered universe of men living alone? Would it feel as though hed dashed out for a haircut, or for dish soap, and could return at any moment? Or would the house have the aura of the abandoned, like a woman whose husband runs out to gas up the car and forgets to come home?