ALSO BY WILLIAM BRYANT LOGAN

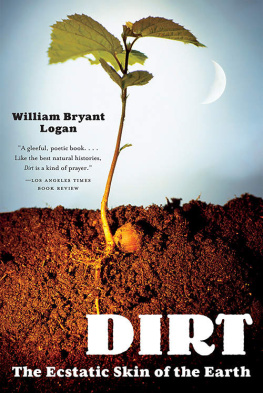

Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth

For Bear

and Nora

Not unfortunately the universe is wild....

W ILLIAM J AMES

Its not what we see, but what we see in it.

E DGAR A NDERSON

TO J OHN B RINCKERHOFF J ACKSON

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I AM NEITHER a botanist nor a historian. This book could not have been written without the help of many generous people and scholars from around the world of oak.

Let me first of all thank Professor Kevin Nixon of Cornell University, whose insights on the greatness of oak were crucial to focusing the book. I am also deeply indebted to Ole Crumlin-Pedersen and his staff at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, who patiently taught me about Viking ships, as did Arne-Emil Christensen at the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway.

For help on the balanoculture section, I most gratefully acknowledge Sarah R. Mason, whose dissertation on acorns as human food provided a roadmap for my research. Likewise, I am indebted to David Bainbridge, who so far as I know coined the word balanoculture and whose thesis about acorn eating helped shape my own. Suellen Ocean was generous with her time and her recipes, both of which helped me learn to make acorn dishes for myself. Delfina Martinez of Hopland, California, welcomed a perfect stranger and answered his numerous intimate questions about her childhood.

My research in England was wonderfully and unexpectedly helped by Brian Roby, the proprietor of Felton House, Hereford, who sent me all over the countryside in search of trees, timber-framed houses, and craftsmen whom he knew. Steve Potter, forester, showed me the forest from which the new roof for Windsor Great Hall had come. Mark Hicks of Capps & Capps Ltd. discussed their work on that project and timber building in general. He walked through his woodyard, commenting on the uses and qualities of each piece. John Green of Border Oak, Herefordshire, walked me through the whole process of timber-framing, using his companys own products as examples, and Julian Monkley, cabinet maker, showed me through the timber-framed house hed built himself.

Other craftsmen were equally generous with their time and knowledge. Mike Greason, consulting forester, walked me through the snowy woods, evaluating oaks and explaining their insides by looking at their outsides. David Proulx, the longtime cooper in residence at Sturbridge Village, showed me the steps in caskmaking and the careful judgment required to get it right.

Dwight Demilt, the carpenter in charge at the USS Constitution, was very generous with his time and expertise. He led me from stem to stern and top to bottom of the ship, explaining everything as he went. Librarian Kate Lennon-Walker at the Constitution Museum was a great help in finding references not only to the ship itself but also to many matters related to sailing and sailing ships in general.

The tree physicist Klaus Mattheck was also important to me, not only as a general teacher about the ways of trees but also for his pioneering ideas about using tree structure as a model for better industry.

So many people helped shape this book. I also thank Ray Tanner, now deceased, and Bob Lansing for their comments on the woods and town where they were raised. Rabbi and Mrs. Kornbluth were an education to me about real respect for the natural world.

Many thanks too to Wayne Cahilly and to David Sassoon, who read the manuscript critically.

There would have been no book without John Barstow, who asked me to write it and who never lost interest through many delays, or without Alane Mason, my editor, and Alessandra Bastagli, her assistant. Alane insisted that the book be as good as it could be and tirelessly supported it.

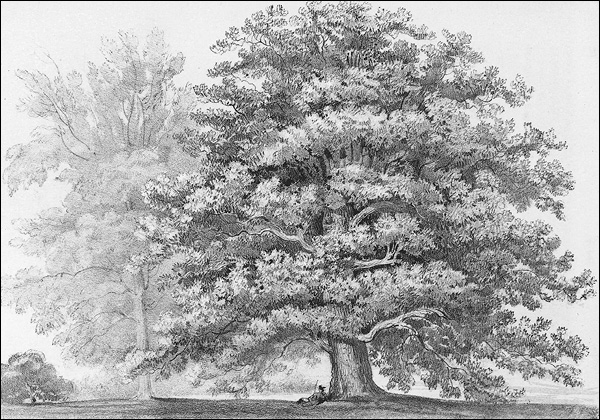

My deepest thanks also go to my wife, Nora H. Logan, whose beautiful illustrations are an important part of the book. She and our children, Sam, Jake and Eliza, were also endlessly patient when Dad disappeared into the trees yet again. Finally, I am indebted to the men of Urban Arborists, especially to Fernando, who have been my constant companions among the trees for more than a decade.

I N T HE M IDDLE OF

THE W ORLD

T REES ARE THE tallest, most massive, and longest-lived creatures on earth. But oaks hold none of the records. The oak is not the tallest tree. That distinction belongs to a redwood in northern California, which tops out at about 368 feet, easily twice as tall as the tallest oak. Neither is the oak the most massive tree. That honor is held, if you wish, by the General Sherman sequoia in Kings Canyon National Park, weighing in at about two thousand tons, though if you are thinking genetically, the record may instead be held by a clonal aspen grove in Utah that covers more than 106 acres. The oak is not the oldest tree. The bristlecone pine holds that record, at something in excess of 4,867 years. The oak is not the strongest tree. Ebony, teak, and many other tropical woods have greater strength under tension, compression, and shearing forces. And the oak is far from the fastest-growing tree. There is a species of albizia in Malaysia that can grow more than an inch each day; an oak is lucky to do a foot each year. Any old maple, pine, poplar, or eucalyptus can easily outrun the oak.

So what is so special about oaks?

I asked Kevin Nixon, a paleobotanist at Cornell University, who studies the origin of oaks.

Nothing, he said, and paused.

But what is impressive about them is that you can go from Massachusetts to Mexico City and find that the same genusthe oaks, that is, Quercus is dominant, when there are very few other genera that are even common to both places.

Well, why is that? I asked, trusting that oak held some world record at least.

No reason, he replied nonchalantly.

Quercus hindsii , California white oak (Collection of William Bryant Logan)

It was a good thing we were speaking by phone, since he did not see my cheeks puff out and redden as I tried to keep from spluttering. There was an awkward silence.

Its like the chambered nautilus, he continued, at last. The Nautilus genus was once very diverse, but then it overspecialized until it could only live in one particular niche in one particular way.

Go on, I said. He had my interest.

But the oaks never overspecialized, he continued. They never found a niche. They are so successful exactly because there is no reason that they are. Restricted distribution only happens when there is just one reason for a creatures success.

Here was an unexpected and tantalizing idea. The persistent, the common, the various, the adaptable has value in itself. The oaks distinction is its insistence and its flexibility. The tree helps and is helped in turn. It specializes in not specializing.

And indeed, the champion trees are niche holders: The giant redwood can only survive on a cool, fogbound band of warm coast. The ancient bristlecone pine only grows on one high mountain ridge, where no pest can survive long enough to attack it. Ebony needs great heat, great water, and little variation in temperature to make its strong, flexible, durable wood. The clonal aspen thrives and expands only at altitudes and on exposures high and difficult enough to ward off competing species. None of these record trees thrives throughout the temperate zone, in the middle of the world, where the unexpected is commonplace.

Next page

![Logan - Sprout lands [Release date Mar. 26, 2019] : tending the endless gift of trees](/uploads/posts/book/128344/thumbs/logan-sprout-lands-release-date-mar-26-2019.jpg)