www.headofzeus.com

To Jack and Flora, with love

Contents

The wisdom of trees

Enlightenment Autumn Brown and sticky Trees of liberty Foresight

T REE TALE : THE B IRCH

What trees do Trees with latitude Solar panels Family tree Pioneers

T REE TALE : THE R OWAN

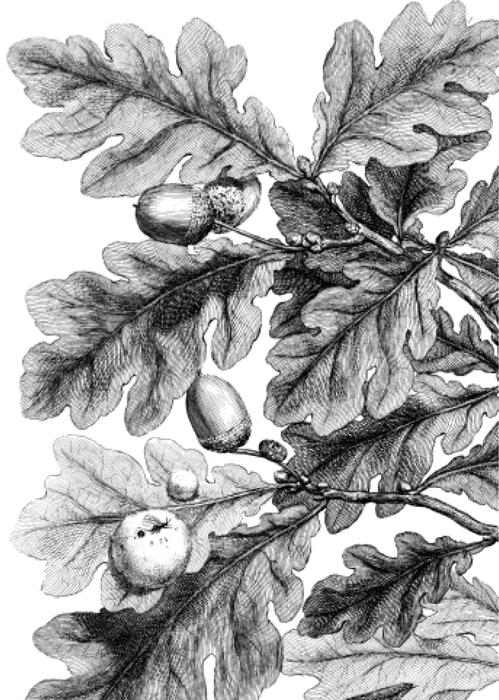

Sex before insects Spring Making babies Pioneers Massive oak The human hand

T REE TALE : THE A PPLE

This means war Conventional weapons Plan B Battle of the trees The wood of life

T REE TALE : THE Y EW

A palette of forests Life in the woods Saint Columbas coppice The rarest tree Woodwards and Pallisters

T REE TALE : THE S COTS PINE

Useful lessons Getting the point Terraforming Ascension Island The luthier

T REE TALE : THE H AZEL

Axe, adze and wedge Summer The first carpenters Stonehenge decoded? The Nobel Prize-winning woodworker

T REE TALE : THE B EECH

Hormones Machines Hydraulics Bodgers How tall can a tree be? Standing up straight

T REE TALE : THE H AWTHORN

Material gain Making charcoal The sword in the stone Seahenge Riddley Walker Colemen and Colliers

T REE TALE : THE H OLLY

Size matters The first house Houses for the dead Firewood At home with Saint Columba

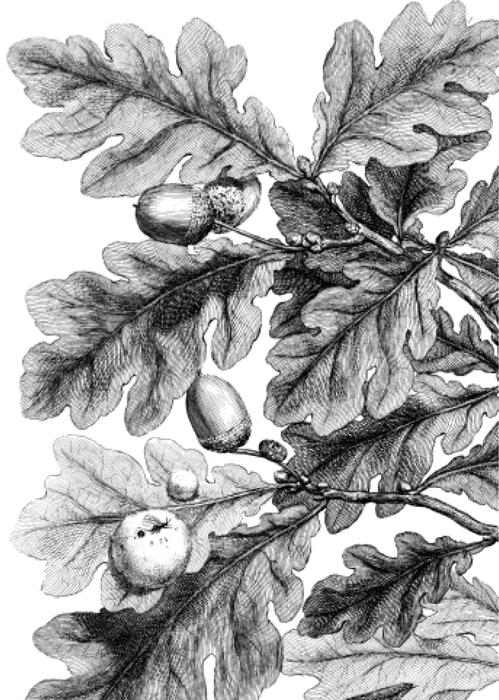

T REE TALE : THE O AK

How old is it? Trees of Middle-earth Chesapeake End of the age How to spot an ancient wood

T REE TALE : THE E LM

Heroes A few words on paper How to buy a woodland Forest gardens Ashington Winter

T REE TALE : THE A SH

Woodlanders

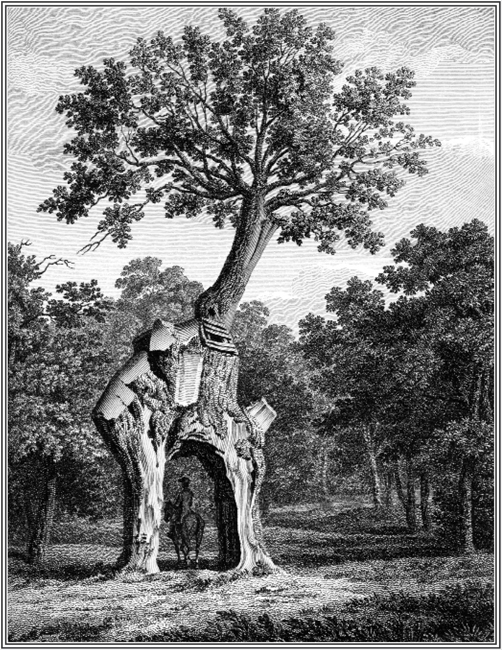

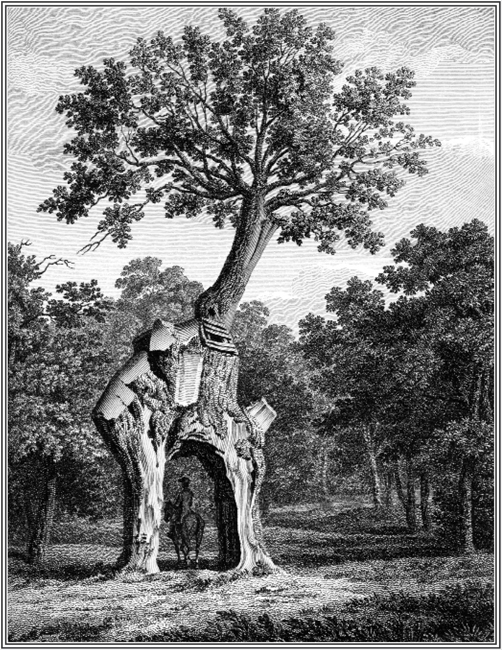

T HE G REENDALE OAK

( north-west view )

This venerable oak tree used to grace the estate of Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire, on land enclosed from Sherwood Forest. So vast was the trees girth that its owner, the Duke of Portland, decided to gut it in 1724; he promptly won a bet that a coach and six could be driven through it. Sadly, his drastic sculpting set in an inevitable decline and, like an enfeebled invalid, the once virile oak came to depend on crutches in its later years.

The wisdom of trees

Truly trees are beings. We feel that to be so. Hence their silence, their indifference to us is almost exasperating.

J OHN S TEWART C OLLIS

H UMANS HAVE a natural empathy with their fellow creatures. They will rescue a stranded ladybird and fish a carrot out of their pocket for a lonely donkey. They know that dogs like to play and be part of the gang; that cats look down on them; that pigs regard them as equals. Things have their place. Heaven knows, humans can be sentimental about even the most unprepossessing animals: we credit them with all sorts of emotions and intelligences on the basis that they too can feel pain, conceive of the world around them and have some sort of attachment to their offspring. We think, therefore we are; animals are, therefore they think.

What about trees? Trees are an alien life-form. Like all living things they breathe and reproduce, but do they feel pain like animals? Do they think? The answer is simple: they do not think, because they have no brains; they do not feel, because they have no nervous systems. They cannot, in any sense, be described as intelligent. They have no plan or strategy for defence or reproduction; they cannot choose their sexual partners, nor decide where to live their lives. Trees do not make choices. They share no organs with members of the animal kingdom, unless one offers the superficial analogy that bark is like skin. Trees know, literally, nothing . And so the whole idea of trees possessing wisdom is pathetic fallacy.

And yet, a lifelong admiration and affection for trees, woods and forests can hardly dispel the impression that they are damned clever. Those plants with a stick up the middle (in Colin Tudges words), sixty-thousand species of them, are chemically and mechanically sophisticated, sometimes dazzlingly so. They are more resilient than any animal, and some live for several thousand years. Their reproductive capacities are so subtle and refined that it is hard not to credit them with cunning. Trees communicate with one another and strike up partnerships and alliances that one yearns to call strategic, or purposeful. There are rumours in the scientific community that they may be able to manipulate sunlight in quantum parcels to make their leaves more efficient.

Hundreds of generations of humans have regarded trees as a source of wisdom: they have been consulted by holy men, by kings, queens and wise women. They have been thought of as sacred, as embodying the spirits of dead ancestors. They are deployed as metaphors for youth and old age; for solidity and sagacity; for fertility, virility and sterility, and for ancestry and evolution. Trees can seem chaste, like the graceful, slender rowan on a rocky hillside; irascible, like an ancient stag-headed oak standing apart in a field; magnificent, like a hundred-foot-tall beech tree with its elephantine muscular grey trunk. In Allouville, Normandy, the chapel of Chne is built into a living oak tree which is more than eight-hundred years old. On the slopes of Mount Etna the Hundred Horse Chestnut is so vast that it could shade in its hollow trunk the hundred men of a mounted party in a thunderstorm (hence its name). More modestly, the writer and woodsman John Stewart Collis used a favourite ash tree as a summer tool shed. In Africa baobab trees have been used as prisons and classrooms, sanctuaries and water reservoirs; in Ireland, hollow trees became hermitages for Dark Age monks seeking solitude. In Germany, early Christian missionaries cut down trees that had been sacred to the native pagans, as if afraid to let them live. In India, the fig tree is not only sacred but also an embodiment of the human psyche and a dwelling for the gods: the tree beneath which the Buddha gained enlightenment. Trees have their practical uses, to be sure; but they are never just practical. Our affinity with them runs deep, and it is complex.

Next page