Introduction

P ines are trees of wind and fire and light. Wind carries their pollen from one tree to another, disperses the seeds of many and fans the fires that are often their nemesis. Fire feeds on the resin-saturated wood of mature and dead pines, and fertilizes the ground for their seeds to germinate. For some species it is an essential part of their natural history, the heat opening their cones and releasing seeds; and in fire-cleared ground pine seedlings receive plenty of light. Fire and light run through the history of pines in human culture as well, together with a paradoxical association with water and seafaring, and ambiguity in the vocabulary surrounding them.

There are around 100 to 110 species of pine (genus Pinus, family Pinaceae), depending on the state of taxonomic thought and the authority consulted. They are evergreen conifers, bearing seeds in woody cones and needle-like leaves in bundles. As a group, they are not fussy about soils. Individual species have their foibles, but the genus provides examples that grow in alkaline soils such as dolomitic limestone, on sand dunes, in serpentine soils poor in nutrients and high in toxic minerals, and in boggy areas.

Pine trees need seasons. As the genus is frequently associated with northern climates, these are usually stated in terms of warm and cold, of spring, summer, autumn and winter; but some species of pine belong to the tropics, where the important distinction is between wet and dry seasons.

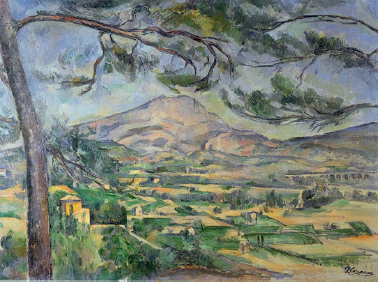

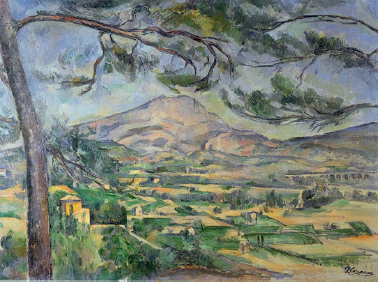

Paul Czanne, Mont St Victoire, c. 1887, oil on canvas. Pine trees recurred in the work of Paul Czanne, who, in a letter to Emile Zola, reminded the author of the pine on the banks of the Arc, whose needles had protected them from the sun, and wished that it should be preserved from the woodchoppers.

In many peoples minds, pines are associated with the unrelieved dark green of North American boreal forests or the taiga of Eurasia. They grow where many other plants find it difficult to flourish in subarctic conditions, on high mountains, in semi-desert and on sea-shores but are rarely the exclusive tree species in these places. They keep company with other conifers, birches and oaks, with shrubs such as juniper, heather and bilberry, or with the vegetation known as sagebrush or chaparral in North America, or Mediterranean maquis species, depending on the region. Some species grow in savannah-like grassland. In warm climates they tend to be mountain species, but some grow down to sea level. They are tough survivors, tolerant of unpromising environments, although competition from other trees will crowd them out in good soil. In such circumstances they retreat gradually to less hospitable territory, and subsist there until conditions are right for re-expansion. They may appear as pioneers on open ground fire-cleared soil, abandoned fields, clearings created by the fall of large trees but in their shade grow species nursed along in their shelter, species that in turn succeed them, stealing the light from any young pines.

The idea of a domesticated pine seems odd, but one does exist: umbrella pine, also called Italian stone pine (Pinus pinea), of the Mediterranean. But it is Linnaeuss Pinus sylvestris, meaning the pine of the woods, known in English as Scots pine and named in many other languages pio bravo, gemeine keifer, sosna lesnaya, pin sylvestre that northern Europeans think of as the archetypal pine tree. A tree with a vast distribution, of high latitudes and cold winters, of glaciated mountains from the Atlantic coasts of Scotland and Norway to the Pacific shores of Russia, it gave little hint to early European explorers of the richness and variety of pine species they would find in North America, China and Southeast Asia.

The taxonomy of pine trees is complex, and they are of huge ecological and economic importance, leading to a vast and unmanageable literature on the subject. They also have deep cultural and social significance. As native forest, they provide special habitats and a connection with the spiritual world; their tenacity is admired in the Far East, and their foliage, shapes and cones have intrigued artists throughout the ages. As plantations the trees are harvested for timber, to make fibres and card, and as garden trees they provide attractive forms and colour. The genus includes one of the oldest living life forms on the planet; perhaps most importantly, the products of pine trees were essential as preservatives and solvents in a pre-mineral oil world.

one

The Natural History of Pine Trees

P ines, genus Pinus, are native to the northern hemisphere North America, Eurasia and down through China into Southeast Asia. The British have a limited view of them, unless they have had the cause or curiosity to observe many species. Scots pine is most familiar to them: a handsome tree with short, dark foliage, small cones and orange bark on its upper branches. They might gaze, perhaps disparagingly, across blocks of plantation conifers, unaware that they are looking at lodgepole pine (P. contorta), native to North America, pass shelter belts of P. nigra, commonly known as either Austrian or Corsican pine, or admire ornamental specimens of Japanese black pine (