Mason - The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions

Here you can read online Mason - The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Pavilion Books;National Trust Books, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

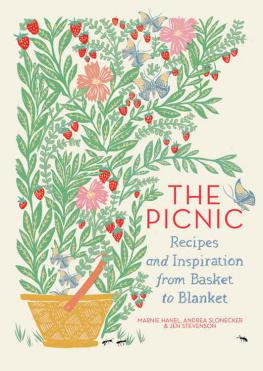

- Book:The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions

- Author:

- Publisher:Pavilion Books;National Trust Books

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Laura Mason

Find a picturesque picnic spot and create your own unique dining space.

Eating outdoors, be it a picnic, a barbecue or a campfire fry-up, brings out an optimistic streak in the British. Appetites will be sharpened by the fresh air and there is an opportunity to lounge on the grass or seashore, to admire a wonderful view, or to feel a sense of freedom. English literature is full of these events both real and imagined. Sometimes it might be admitted that conditions were less than ideal, and the weather is frequently blamed as if everyone imagined that the usual changeable climate might behave itself simply because someone had arranged an outdoor party.

What an attraction the picnic has for us, what a hold on our imagination. All the elements that feed into our ideas of the event can be seen in the tangled strands of its history. The word, of mysterious origin, arrived in the English language in the late 18th century and quickly came to mean a pleasure excursion including an outdoor meal, often one to which each person made a contribution by providing some food.

There were precedents for eating outside: hunting parties and informal collations taken in special banqueting houses, set on the roofs of mansions or at special viewpoints in the grounds of large houses. But at about this time, the Romantic movement also brought new ideas about the joys of being outdoors, especially in rugged scenery. William and Dorothy Wordsworth and their circle were notable picnickers.

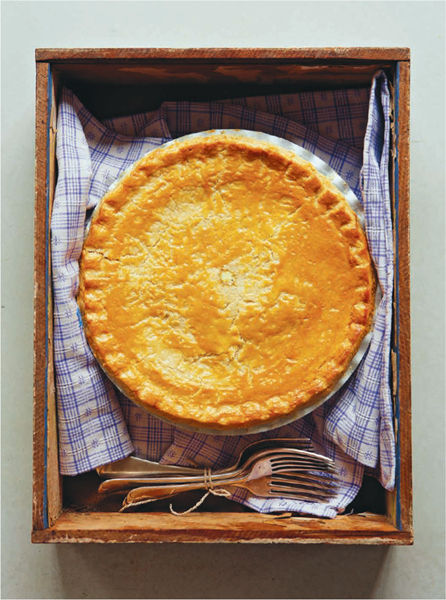

However much food we might pack into the boot of the car, we are amateurs compared to the Victorians. Mrs Beetons Book of Household Management (1861) provided a menu, surely idealised, for a picnic for 40 people. Large quantities of cold cuts and meat pies, lobsters, baskets full of salad, jar upon jar of stewed fruit, pastry of various descriptions, a large Christmas pudding (this must be good), fruit, cheese and the wherewithal for tea bread, butter and three types of cake are all listed. Ale, ginger beer, soda water, lemonade, sherry, claret, champagne and brandy are suggested as beverages. The outdoors not only sharpens the appetite it also sharpens the thirst.

The informality of eating outside still has great appeal, but it must have been appreciated much more in the past. James Tissots painting The Picnic (1876) shows some of the joys of such an occasion. The young men and women of the party flirt in an urban setting, the garden of his own home in London, and there is cake, bread and butter, and a kettle is set on a spirit burner in the foreground. It is autumn, the horse chestnut leaves are golden and brown, and scarves, caps, rugs and shawls are all evident. The season, although late, is clearly no obstacle to frivolous enjoyment of food and company outdoors.

Further freedom, which we take for granted, came with the invention of the motor car. Picnics for Motorists, by Mrs Leyel, was published in 1936, with menus of mousses and galantines, jellied cold dishes, extravagant pies and meat dishes. Everything seemed to contain truffles, said the friend who lent her copy to me. This isnt true, but the book has the aura of a time when money was no particular object, and ladies of leisure, although they might have learnt their way around a kitchen, undoubtedly had someone to do the washing-up while they packed a basket of delicacies and drove off to meet friends at some beauty spot. Mrs Leyel was an advocate of the thermos flask, although many took a kettle along and made tea fresh as required.

Most importantly, a picnic is an escape, a break from routine. Ambrose Heath wrote of this in Good Sandwiches and Picnic Dishes (1948): For children it is an ineffable glance into Paradise, when the shackles of restraint are unloosed, and for far too brief a while realities withdraw. He captures the curious tension, evident in all the best picnics: a mixture of spontaneity and good planning. The sense of time apart is emphasised again and again in descriptions of good picnics.

Ambrose Heath makes another very important point: it is best to agree a destination in advance, for if you set off with no particular place in mind, you may well find yourself shot out upon some unlovely roadside with no more than an unappetising row of modern brick cottages and a farmyard midden or these days, more likely, its modern equivalent, the car park of a motorway services.

The food and destination are within ones control, but picnics have many potential hazards weather, wasps, stray animals. Ive sat in the car drinking tea from a flask while heavy rain blurred a view of tarmac, and Ive cowered behind a wall in a hailstorm, trying to eat disintegrating cake from frozen fingers. Elizabeth David described an unnerving experience during a picnic in India (the members of the British Raj were great picnickers), of eating while surrounded by a circle of stray dogs that howled in unison. Another intrusion into the bucolic ideal is shown in the late 19th-century painting, The Pigs Picnic, by William Weekes. A broad damask cloth is spread on the ground, elaborately set with cutlery and glasses. A stack of plates, bottles of champagne, a neatly garnished pie and a roast of beef await the company. The lone guardian of all this, a small boy, lies asleep, his shiny top hat discarded, while unobserved, a large black pig advances with a mixture of caution and curiosity across the snowy cloth towards a brilliant carmine lobster. Sometimes, one feels that lurking disaster is also part of the picnic mix, to be enjoyed retrospectively.

Provisions for travellers and food for walks have an element of necessity about them. They need to be easy to carry and easy to eat and to satisfy. There is the possibility of being tetchy and bored with carrying the picnic, but the probability of an appetite sharpened by an early start and chilly weather. Eating a meal outdoors is a product, not the object, of the day. But there is no reason why it should not be good and pleasurable, and a well-made sandwich from home cheers a long journey in a way that no pre-packed offering can. During my childhood there was a very clear division between taking a picnic for a day out and taking food because one was on a journey. It was nicer, and of course cheaper, to take food from home and not be at the mercy of cafs or railway-station buffets. That the food was usually egg sandwiches and a flask of tea, whatever the occasion, was beside the point.

In the English love affair with eating al fresco, the barbecue is a late arrival. It is noticeable that, although many authors from the past would have been familiar with the notion of spit-roasting and cooking on a grid-iron in the kitchen, the idea of carrying this into the outdoors is limited. Grand celebratory events such as ox-roasts aside, few people seem to have grilled their food outdoors (an exception being Sir Walter Scott, whose salmon-fishing expeditions to the Tweed often ended with cooking the catch). As with so much else to do with food, the idea arrived in the mid-20th century. The North American influence burgers, steaks and a plethora of sauces and foreign holidays, in which the British found themselves salivating at the smells of meat or fish grilled over charcoal on the shores of the Mediterranean, played a large part in the rise of the barbecues popularity. It is difficult to imagine this as a novelty now, when every fine weekend seems to lead to the mass lighting of charcoal across the country, but a barbecue still captures that essential of eating outdoors, a space outside ordinary time, a bit of a party.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

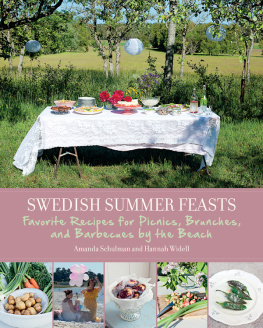

Similar books «The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions»

Look at similar books to The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Picnic Cookbook: Outdoor Feasts for All Occasions and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.