In Memoriam

Victoria Chandler

19501999

Contents

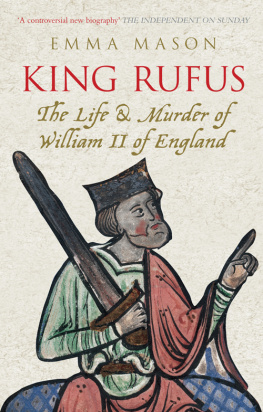

T he reign of William II has had a compelling fascination for me since I gave my very first lecture in English history on this topic when I joined the teaching staff of Birkbeck University of London. While preparing that presentation, I was struck by the contrast between the positive achievements of the reign and the negative light in which William was viewed by most historians who were active down to the late 1960s. Ideas voiced in that lecture were developed in a paper delivered to a staff-student seminar for members of the Birkbeck Faculty of Arts. The interest generated then encouraged me to develop these ideas still further in my first article on the subject, William Rufus: myth and reality, which evoked wider discussion. Some years later, I published a second article on the subject, William Rufus and the Historians, examining the treatment of the king by writers over successive generations. I concluded with a brief outline of why, in the light of international political tensions of the time, it seemed probable that the kings death was not accidental. The preparation of a further paper, William Rufus and the Benedictine Order, convinced me that in some important respects the monastic writers of the twelfth century conveyed a misleading impression of the kings dealings with the religious houses.

When my work on William II reached this stage, Jonathan Reeve of Tempus invited me to write a book on the subject, a biography rather than a thematic reign of.... Plenty of information about the king is found in the work of those who wrote within a few decades of his death, but this was all slanted in one direction or another. In drawing on these accounts, my book could readily have been subtitled A Study in Spin. Writers in the ancient world already practised spin, and its use continued down the centuries. In the early twelfth century, monastic historians used negative spin with gusto as they attacked a ruler who siphoned off clerical wealth to fund his military projects. Positive spin, on the other hand, is found in the depiction of William II in Geoffrei Gaimars Estoire des Engleis . This writer used to be regarded as a mere entertainer, but recent studies of him and of his source of information when writing of this reign indicate that his positive depiction of William and his court circle should be taken seriously.

The further back in time a historical subject existed, the sparser and more problematic the sources become, so that detection and deduction increasingly come into play. No one can claim to be truly comprehensive when writing on a subject so far back in time as William II. Those readers who enjoy detective stories will find plenty of conflicting sources here from which to draw their own conclusions. The ultimate challenge comes in deciding what did happen in the New Forest on 2 August 1100. Did the abbot of Gloucester, the old woman and the huntsmen know something which was covered up by the establishment of the next reign? And who were those who transmitted the name of Raoul dEquesnes so discreetly down the generations until responsibility for the kings death was no longer a politically sensitive issue?

Among the many people who have given me specialist advice during the preparation of this work, I am particularly grateful to three who generously allowed me to see work of their own in advance of its publication: Val Wall, in respect of her paper on the Venoiz family, ancestors of Constance Fitz Gilbert, the patron of Geoffrei Gaimar; Ian Short, translator of Gaimars LEstoire des Engleis ; and Neil Strevett, in respect of his University of Glasgow PhD thesis, The Anglo-Norman Aristocracy Under Divided Lordship 10871106 (2005).

Others who have been particularly helpful include Alison Finlay, who responded to repeated calls on her expertise in Old Norse; John Hayward, who resourcefully found many of the illustrations; and Richard Mortimer, Keeper of the Muniments of Westminster Abbey, who enthusiastically collaborated in the hunt for the real find-spot of the sculptured capital depicting William II and the monks. Janet Barnes and Penny Wallis both provided additional illustrations.

My ideas on the reign of William II have developed during conversations with many of the participants in the annual Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman Studies. Individuals both there and elsewhere have, over several years, kindly given me items of bibliography or clarified points of detail. Those to whom my thanks are due include Bill Aird, David Bates, Martin Biddle, David Crouch, Katherine Edwards, John Gillingham, Roy Hart, Chris Lewis, Sharon Lieberman, Mark Philpott, Rosemary Power, Susan Reynolds, Richard Sharpe, Matthew Strickland, Naomi Sykes, Kath Thompson and Ann Williams. Jane Dobson expertly and energetically word-processed the text to publication standard.

The dedication is to the memory of a kind friend, a brave woman and a dedicated medieval historian.

CHAPTER ONE

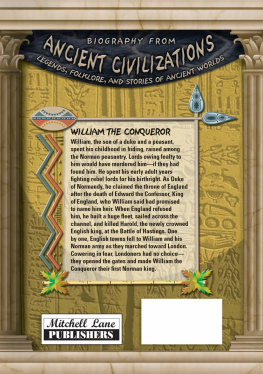

W illiam II (10871100) was formally styled throughout his reign as William, King of the English (sometimes adding by the grace of God), William, King of England or, in a formal record, as King William the younger.

Red hair perhaps still recurred in the Conquerors family, due to its Viking ancestry, but writers working in England in the twelfth century are agreed that William, as an adult, had fair hair, variously described as rather yellow, or blond. Youthful red hair can fade to golden brown in an adult. This perhaps happened in Williams case, while his beard retained its original colouring. Equally, though, he may have inherited the very fair north-European skin type of those whose face quickly turns red after eating and drinking or after exposure to strong sunlight or wind.

Williams nickname is first used, in its Latin form, by writers working in French-speaking lands. Guibert, Abbot of Nogent-sous-Coucy, writing between 1114 and 1124, stated that the king was nicknamed Rufus because he was red: ( qui Rufus, quod et erat, cognominabatur ).

William of Malmesbury described the king as stockily built, with a ruddy complexion; his rather yellow hair centrally parted; his eyes of indeterminate colour, containing bright specks; physically very strong, despite his moderate height, and with rather a paunch. He was not an accomplished speaker, and when he fell into a temper he had a marked stammer.

Objective accounts of the reign written by those close to the centre are non-existent. The Canterbury monk Eadmer, biographer of Archbishop Anselm (10931109), also wrote the Historia Novorum ( History of Recent Events ) essentially, in his view, a prolonged conflict between those exercising royal and ecclesiastical power. Eadmers hero Anselm is depicted in a prolonged confrontation with King William, who is depicted in a uniformly bad light. Reading between the lines of Eadmers narrative, and of those of other monastic writers, we gain a distinct impression that the king intentionally shocked his clerical opponents by making sensational remarks from time to time, and that earnest bystanders gained a frisson from these, then drew on them to provide good copy for their tendentious accounts of the reign.

Both of Eadmers major works, his Vita Anselmi ( Life of St Anselm ) and his Historia Novorum , rely largely on notes which he took when travelling in the company of the archbishop, from soon after Anselms election to Canterbury. These narratives have the strengths and limitations of lively eyewitness reporting, selectively presented to give only the archbishops viewpoint in his confrontations with King William. Eadmer began writing the Vita Anselmi during the 1090s, but around 1100 the archbishop discovered what he was doing. He asked to see the work and then corrected various points, suppressed some, changed the order of others and approved the rest. A few days later, though, he told Eadmer to destroy the manuscript. The order was obeyed literally, but not in the spirit. Eadmer secretly made a copy, and resumed work on it after Anselms death. Consequently, the work is very full when it covers the dealings of King William with the archbishop but, since note-taking was subsequently debarred, there is far less on Anselms dealings with the kings brother and successor, Henry I. This imbalance inadvertently reinforced King Henrys own claims to be altogether a better king towards his subjects (including the clerics) than William had been. What is more, the detailed version of the archbishops dealings with King William was that which, thanks to Anselms revision of the text, he himself wanted to be recorded for posterity. The Vita Anselmi is a valuable work in many respects, but it is not an objective depiction of William II.

Next page